- Soccer, communists, fascists, and Yugoslavia Richard Mills (interview), Jacobin

- Over- and under-reactions in politics Chris Dillow, Stumbling & Mumbling

- How a controversial non-violent movement has transformed the Israeli-Palestinian debate Nathan Thrall, Guardian

- Sovereignty, confusion, and the international order Nick Danforth, War on the Rocks

The Real Cost of National Health Care

Around early August 2018, a research paper from the Mercatus Center at George Mason University by Charles Blahous made both the Wall Street Journal and Fox News within two days. It also attracted attention widely in other media. Later, I thought I heard sighs of satisfaction from conservative callers on talk show radio whenever the paper came up.

One figure from the study came and stayed at the surface and was quoted correctly many times (rare occurrence) in the electronic media. The cost of what Senator Sanders proposed with respect to national health care was:

30 trillion US dollars over ten years (actually, 32.6 over thirteen years).

This enormous number elicited pleasure among conservatives because it seemed to underscore the folly of Senator Bernie Sanders’ call for universal healthcare. It meant implicitly, federal, single-payer, government-organized health care. It might be achieved simply by enrolling everyone in Medicare. I thought I could hear snickers of relief among my conservative friends because of the seeming absurdity of the gigantic figure. I believe that’s premature. Large numbers aren’t always all they appear to be.

Let’s divide equally the total estimate over ten years. That’s three trillion dollars per year. It’s also a little more than $10,000 per American man, woman, child, and others, etc.

For the first year of the plan, Sanders’ universal health care amounts to 17.5% of GDP per capita. GDP per capita is a poor but not so bad, really, measure of production. It’s also used to express average gross income. (I think that those who criticize this use of GDP per capita don’t have a substitute to propose that normal human beings understand, or wish to understand.) So it’s 17.5% of GDP/capita. The person who is exactly in the middle of the distribution of American income would have to spend 17.5% of her income on health care, income before taxes and such. That’s a lot of money.

Or, is it?

Let’s imagine economic growth (GDP growth) of 3% per years. It’s optimistic but it’s what conservatives like me think is a realistic target for sustained performance. From 1950 to 1990, GDP per capita growth reached or exceeded 3% for almost all years. It greatly exceeded 3% for several years. I am too lazy to do the arithmetic but I would be bet that the mean annual GDP growth for that forty-year period was well above 3%. So, it’s realistic and probably even modest.

At this 3% growth rate, in the tenth year, the US GDP per capita will be $76.600. At that point, federal universal health care will cost – unless it improves and thus becomes more costly – 13% of GDP per capita. This sounds downright reasonable, especially in view of the rapid aging of the American population.

Now, American conservative enemies of nationalized health care are quick to find instances of dysfunctions of such healthcare delivery systems in other countries. The UK system was the original example and as such, it accumulated mistakes. More recently, we have delighted in Canadian citizens crossing the border for an urgent heart operation their nationalized system could not produce for months: Arrive on Friday evening in a pleasant American resort. Have a good but reasonable dinner. Check in Sat morning. Get the new valve on Monday; back to Canada on Wednesday. At work on the next Monday morning!

The subtext is that many Canadians die because of a shortage of that great free health care: It nice if you can get it, we think. Of course, ragging on the Canadians is both fair and endlessly pleasant. Their unfailing smugness in such matters is like a hunting permit for mental cruelty!

In fact, though, my fellow conservatives don’t seem to make much of an effort to find national health systems that actually work. Sweden has one, Denmark has one; I think Finland has one; I suspect Germany has one. Closer to home, for me, at least, France has one. Now, those who read my blogging know that I am not especially pro-French or pro-France. But I can testify to a fair extent that the French National Healthcare works well. I have used it several times across the past fifty years. I have observed it closely on the occasion of my mother’s slow death.

The French national health system is friendly, almost leisurely, and prompt in giving you appointments including to specialists. It tends to be very thorough to the point of excessive generosity, perhaps. Yes, but you get what you pay for, I can hear you thinking – just like a chronically pessimistic liberal would. Well, actually, Frenchmen live at least three years longer on the average than do American men. And French women live even longer. (About the same as Canadians, incidentally.)

Now, the underlying reasoning is a bit tricky here. I am not stating that French people live longer than Americans because the French national healthcare delivery system is so superior. I am telling you that whatever may be wrong with the French system that escaped my attention is not so bad that it prevents the French from enjoying superior longevity. I don’t want to get here into esoteric considerations of the French lifestyle. And, no, I don’t believe it’s the red wine. The link between drinking red wine daily and cardiac good health is in the same category as Sasquatch: I dearly hope it exists but I am pretty sure it does not. So, I just wish to let you know that I am not crediting French health care out of turn.

The weak side of the French system is that it remunerates doctors rather poorly, from what I hear. I doubt French pediatricians earn $222,000 on the average. (Figure for American pediatricians according to the Wall Street Journal 8/17/18.) But I believe in market processes. France the country has zero trouble finding qualified candidates for its medical schools. (I sure hope none of my current doctors, whom I like without exception, will read this. The wrong pill can so easily happen!)

By the way, I almost forgot to tell you. Total French health care expenditure per person is only about half as high as the American. Rule of thumb: Everything is cheaper in the US than in other developed countries, except health care.

And then, closer to home, there is a government health program that covers (incompletely) about 55 million Americans. It’s not really “universal” even for the age group it targets because one must have contributed to benefit. (Same in France, by the way, at least in principle.) It’s universal in the sense that everyone over 65 who has contributed qualifies. It’s not a charity endeavor. Medicare often slips the minds of critical American conservatives, I suspect, I am guessing, because there are few complaints about it.

That’s unlike the case for another federal health program, for example the Veterans’, which is scandal-ridden and badly run. It’s also unlike Medicaid, which has the reputation of being rife with financial abuse. It’s unlike the federally run Indian Health Service that is on the verge of being closed for systemic incompetence.

I suspect Medicare works well because of a large number of watchful beneficiaries who belong to the age group in which people vote a great deal. My wife and I are both on Medicare. We wish it would cover us 100%, although we are both conservatives, of course! Other than that, we have no complaints at all.

Sorry for the seeming betrayal, fellow conservatives! Is this a call for universal federal health care in America? It’s not, for two reasons. First, every country with a good national health system also has an excellent national civil service, France, in particular. I have no confidence, less than ever in 2018, that the US can achieve the level of civil service quality required. (Less in 2018 because of impressive evidence of corruption in the FBI and in the Justice Department, after the Internal Revenue Service).

Secondly, when small government conservatives (a redundancy, I know) attempt to promote their ideas for good government primarily on the basis of practical considerations, they almost always fail. Ours is a political and a moral posture. We must first present our preferences accordingly rather than appeal to practicality. We should not adopt a system of health delivery that will, in ten years, attribute the management of 13% of our national income to the federal government because it’s not infinitely trustworthy. We cannot encourage the creation of a huge category of new federal serfs (especially of well-paid serfs) who are likely forever to constitute a pro-government party. We cannot, however indirectly, give the government most removed from us, a right of life and death without due process.

That simple. Arguing this position looks like heavy lifting, I know, but look at the alternative.

PS I like George Mason University, a high ranking institution of higher learning that gives a rare home to conservative American scholars, and I like its Mercatus Center that keeps producing high-level research that is also practical.

Nightcap

- Reclaiming Full-Throttle Luxury Space Communism Aaron Winslow, Los Angeles Review of Books

- Elves and Aliens Nick Richardson, London Review of Books

- Imperialism, American-style Michael Auslin, Claremont Review of Books

- The Congo reform project: Too dark altogether Angus Mitchell, Dublin Review of Books

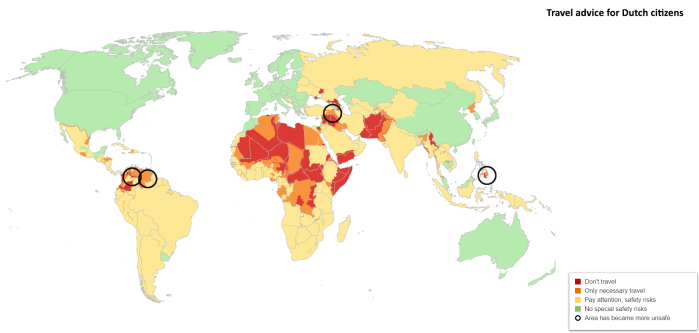

Eye Candy: travel advice for Dutch citizens

Interesting map, for a few reasons. The United States is in green, which means there are “no special safety risks” to worry about. What I take this to mean is that as long as you stay out of, say, North Sacramento, or East Austin, when the sun goes down you’ll be safe.

The “pay attention, safety risks” label makes quite a big jump in my conceptual understanding of this map. What this warning means is that if you are particularly stupid, you won’t end up getting mugged and losing your wallet (like you would in green areas), you will instead end up losing your life or being kidnapped for ransom (or slavery).

This is quite a big jump, but it makes perfect sense, especially if you think about the jump in terms of inequality and, more abstractly, freedom.

Nightcap

- The return of Henry George Pierre Lemieux, EconLog

- The politics of purity and indigenous rights Grant Havers, Law & Liberty

- The Ottoman Empire’s first map of the United States Nick Danforth, the Vault

- The age that women have babies: how a gap divides America Bui & Miller, the Upshot

Nightcap

- Death of a Marxist Vijay Prashad, The Hindu

- We’re on the threshold of a third wave of globalization. What should we expect? Branko Milanovic, globalinequality

- Turkey kills PKK’s leader in Iraq Amberin Zaman, Al-Monitor

- France’s second-class citizens Haythem Guesmi, Africa is a Country

Naipaul (RIP) and the Left

The most interesting reflection on V.S. Naipaul, the Nobel Prize winner who died earlier this week, comes from Slate, a low-brow leftist publication that I sometimes peruse for book reviews. Naipaul, a Trinidadian, became loathed on the left for daring to say “what the whites want to say but dare not.”

The fact that Slate‘s author tries his hardest to piss on Naipaul’s grave is not what’s interesting about the piece, though. What’s interesting is what Naipaul’s wife, a Pakistani national and former journalist, has to say about Pakistan:

[…] she smiled and asked if I knew what Pakistan needed. I informed her that I did not. “A dictator,” she replied. At this her husband laughed.

“I think they have tried that,” I said, doing my best to stay stoic.

“No, no, a very brutal dictator,” she answered. I told her they had tried that, too. “No, no,” she answered again. Only when a real dictator came in and killed the religious people in the country, and enough of them that the streets would “run with blood,” could Pakistan be reborn. It was as if she was parodying a gross caricature of Naipaul’s worst views—and also misunderstanding his pessimism about the ability of colonial societies to reinvent themselves, even through violence—but he smiled with delight as she spoke.

“That’s so American of you,” she then blurted out, before I had said anything. My face, while she had been talking, must have taken on a look of shock or disgust. “You tell a nice young American boy like yourself that a country needs a brutal dictator and they get a moralistic or concerned look on their face, as if every country is ready for a democracy. They aren’t.”

Damn. This testy exchange highlights well what the developing world is facing, intellectually. Religious conservatives heavily populate developing countries. Liberals, on the left and on the right, in developing countries are miniscule in number, and most of them prefer, or were forced, to live in exile. Liberty is their highest priority, but the highest priority of Western elites, whose support developing world liberals’ desperately need, is democracy, which empowers a populace that cares not for freedom.

So what you get in the developing world is two kinds of autocracies: geopolitically important autocracies (like Pakistan), and geopolitically unimportant autocracies (think of sub-Saharan Africa).

That Naipaul and his wife had the balls to say this, for years, is a testament to the magnificence of human freedom; that Leftists have loathed Naipaul for years because he had pointed this out is a bitter reminder of why I left the Left in the first place.

By the way, here is Naipaul writing about the GOP for the New Yorker in 1984. And here is my actual favorite piece about Naipaul.

10 horrific ways to die (RCH)

Yes, that’s the subject of my weekend column over at RealClearHistory. An excerpt:

4. Cutting off limbs/flaying. The English version of being hanged, drawn, and quartered involved removing genitals, but did any other society in history stoop so low? Um, yes. Not only have penises and/or testicles been removed and vaginas flayed, but they have sometimes been displayed as trophies, eaten, or converted into jewelry. Genitals aren’t the only limbs to have been removed over the years. Fingers and toes, tongues, breasts, eyes, ears, lips, nipples, noses, kneecaps, fingernails, eyelids, skin, and bones have all been forcibly removed over years by governments exacting punishment. Aside from the removal of genitals, flaying is probably the worst of the bunch. That’s when you beat somebody so hard that their skin comes off.

I had a lot of fun writing this, and I suspect my ever-so-patient editor had a lot of fun reading (and editing) it. I hope you enjoy it too! Here’s the rest of it.

Nightcap

- World War II and the point of Surrealism Sophie Haigney, 1843

- Is religion a universal in human culture? Brett Colasacco, Aeon

- Sikh pilgrimages: Hope for a religious corridor Tridivesh Singh Maini, The News

- For centuries, people thought lambs grew on trees Abbey Perreault, Atlas Obscura

Nightcap

- End the double standards in reporting political violence David French, National Review

- Campaign politics and the origins of the Vietnam War Rick Brownell, Historiat

- Hussein Ibish on Muslim identity Irfan Khawaja, Policy of Truth

- Friends of freedom and Atlantic democratization Micah Alpaugh, Age of Revolutions

RCH: Imperialism and the Panama Canal

Folks, my latest over at RealClearHistory is up. An excerpt:

The political ramifications for Washington essentially stealing a province from Colombia were huge. The United States had just seized a number of overseas territories from Spain in 1898, and the imperial project was frowned upon by numerous factions for various reasons. The U.S. foray into imperialism led to governance issues in the Caribbean, where Washington found itself supporting anti-democratic autocrats, and confronting outright ethical problems in the Philippines, where the United States Army was ruthlessly putting down a revolt against its rule. So acquiring a “canal zone” in a country that was baited into leaving another country was scandalous, especially since Colombia’s reluctance to cooperate with France and the U.S. was viewed as democratic (the Colombian Senate refused to ratify several canal-related treaties with France and the U.S.), and the two Western powers were supposedly the torchbearers of democracy. To make matters worse, many elites in Panama, after agreeing to secede in exchange for protection from Colombia, felt betrayed by the terms of the Panama Canal Zone, which granted the United States sole control over the zone in perpetuity.

Please, read the rest.

Nightcap

- The centrality of the church to black life in America Fred Siegel, City Journal

- Obama David Runciman, London Review of Books

- Remembrance of war as a warning Christopher Preble, War on the Rocks

- European culture and its relation to Russian culture Ivan Kireyevsky, Montreal Review

Nightcap

- The renewed relevance of neoconservatism Rachel Lu, the Week

- The idea of a Muslim world is both modern and misleading Cemil Aydin, Aeon

- Democratic socialism threatens minorities Conor Friedersdorf, the Atlantic

- The world economy’s urban future Parag Khanna, Project Syndicate

China and the liberal vision of the Indo-Pacific

Mike Pompeo’s recent speech (titled ‘America’s Indo-Pacific Economic Vision’) at the Indo-Pacific Business Forum hosted by the US Chamber of Commerce in Washington, DC, has been carefully observed across Asia. Beijing has understandably paid close special attention to it. Pompeo emphasized the need for greater connectivity within the Indo-Pacific, while also highlighting the role which the US was likely to play (including financial investments to the tune of $113 million in areas like infrastructure, energy, and digital economy). The US Secretary of State, while stating that this vision was not targeted at anyone, did make references to China’s hegemonic tendencies, as well as the lacunae of Chinese connectivity projects (especially the economic dimension).

The Chinese reaction to Pompeo’s speech was interesting. Senior Chinese government officials were initially dismissive of the speech, saying that such ideas have been spoken in the past, but produced no tangible results.

A response article in the Global Times is significant here. Titled ‘Indo-Pacific strategy more a geopolitical military alliance’ and published in the communist state’s premier English-language mouthpiece, what emerges clearly from this article is that Beijing is not taking the ‘Indo-Pacific vision’ lightly, and neither does it rule out the possibility of collaboration. The article is unequivocal, though, in expressing its skepticism with regard to the geopolitical aspect of the Indo-Pacific vision. Argues the article:

[…] the geopolitical connotation of the strategy may lead to regional tensions and conflicts and thus put countries in the region on alert.

The piece is optimistic with regard to the geo-economic dimension, saying that American investment would be beneficial and would promote economic growth and prosperity. What must be noted is that while the US vision for an ‘Indo-Pacific’ has been put forward as a counter to the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) of China, the article also spoke about the possible complementarities between the US vision for an ‘Indo-Pacific’ and China’s version of BRI. While Pompeo had spoken about a crucial role for US private companies in his speech, the article clearly bats in favor of cooperation between the Indian, Japanese, Chinese, and US governments, rather than just private companies. This is interesting, given the fact that China had gone to the extent of dubbing the Indo-Pacific vision as “the foam on the sea […] that gets attention but will soon dissipate.”

While there is absolutely no doubt that there is immense scope for synergies between the Indo-Pacific vision and BRI, especially in the economic sphere, China’s recent openness towards the Indo-Pacific vision needs to be viewed in the following context.

First, the growing resentment against the economic implications of some BRI projects. In South Asia, Sri Lanka is a classical example of China’s debt trap diplomacy, where Beijing provides loans at high interest rates (China has taken over the strategic Hambantota Project, since Sri Lanka has been unable to pay Beijing the whopping $13 billion). Even in the ASEAN grouping, countries are beginning to question the feasibility of BRI projects. Malaysia, which shares close economic ties with Beijing, is reviewing certain Chinese projects (this was one of the first steps undertaken by Mahathir Mohammad after taking over the reigns as Prime Minister of Malaysia).

Secondly, the Indo-Pacific vision has long been dubbed as a mere ‘expression’ that lacks gravitas in the economic context (and even now $113 million is not sufficient). Developments over recent months, including the recent speech by Pompeo, indicate that the American Department of State seems to be keen to dispel this notion that the Indo-Pacific narrative is bereft of substance. Here it would be pertinent to point out that Pompeo’s speech was followed by an Asia visit to Indonesia, Malaysia, and Singapore.

The US needs to walk the course and, apart from investing, it needs to think of involving more countries, including Taiwan and more South Asian countries like Sri Lanka and Bangladesh in the Indo-Pacific partnership.

The Indo-Pacific also speaks in favor of democracy as well as greater integration, but countries are becoming more inward-looking, and their stands on democracy and human rights are more ambiguous than in the past. Japan is trying to change its attitude towards immigration, and is at the forefront of promoting integration and connectivity within the Indo-Pacific. Neither the US, nor India, Japan, or Australia have criticized China for its human rights violations against the Uighur minority in Xinjiang province.

Here it would also be important to state that there is scope for China to be part of the Indo-Pacific, but it needs to look at certain projects beyond the rubric of the BRI. A perfect instance is the Bangladesh, China, India, Myanmar (BCIM) Corridor, which India was willing to join, but China now considers this project as a part of BRI.

In conclusion, Beijing can not be excluded from the ‘Indo-Pacific’ narrative, but it cannot expect to be part of the same, on its own terms. It is also important for countries like the United States and India to speak up more forcefully on key issues pertaining to freedom of speech and diversity (and ensure that these remain robust in their own respective countries), given that one of the objectives of the Indo-Pacific vision is a ‘Free and Open Indo-Pacific’.

Nightcap

- Lessons of the Westphalian Peace for the Middle East Andreas Kluth, Handelsblatt

- Is Democracy Dying? Francis Fukuyama (interview), Hromadske

- Yes, the Press Helps Start Wars Ted Galen Carpenter, American Conservative

- The Most Hawaiian Stephanie Lee, Coldnoon