from Kevin Vallier, in the latest issue of Isonomia Quarterly.

Don’t forget to check out the rest, which includes essays on Hayek, the geopolitics of Greenland, the nuclear bombing of Nagasaki, and a poem by Robert Frost.

from Kevin Vallier, in the latest issue of Isonomia Quarterly.

Don’t forget to check out the rest, which includes essays on Hayek, the geopolitics of Greenland, the nuclear bombing of Nagasaki, and a poem by Robert Frost.

For those of you on Bluesky, we now are too. Feel free to give us a follow.

Note: This is the third in a series of essays on public discourse. Here’s Part 1 and Part 2

Three years ago, I started this essay series on the collapse of public discourse. At the time, I was frustrated by how left-wing and progressive spaces had become cognitively rigid, hostile, and uncharitable to any and all challenges to their orthodoxy. I still stand by most everything I said in those essays. Once you have successfully identified that your interlocutors are genuinely engaging in good faith, you must drop the soldier mindset that you are combating a barbarian who is going to destroy society and adopt a scout mindset. For discourse to serve any useful epistemic or political function, interlocutors must accept and practice something like Habermas’ rules of discourse or Grice’s maxims of discourse, where everyone is allowed to question or introduce any idea to cooperatively arrive at an intersubjective truth. The project of that previous essay was to therapeutically remind myself and any readers to actually apply and practice those rules of discourse in good-faith communication.

However, at the time, I should have more richly emphasized something that has been quite obviously true for some time now: most interlocutors in the political realm have little to no interest in discourse. I wish more people had such an interest, and still stand by the project of trying to get more people, particularly in leftist and libertarian spaces, to realize that when they speak to each other, they are not dealing with barbarian threats. However, recent events have made it clear that the real problem is figuring out when an interlocutor is worthy of having the rules of discourse applied in exchanges with them. Here is an obviously non-exhaustive list of such events in recent times that make this clear:

All these were obvious trends three years ago and have very predictably only gotten more severe. You may quibble with the extent of my assessment of any individual example above. Regardless, all but the most committed of Trumpanzees can agree that there is a time and place to become a bit dialogically illiberal in times like these. Thus, it is time to address how one can be a dialogical liberal when the barbarians truly are at the gates. The tough question to address now is this: what should the dialogical liberal do when faced with a real barbarian, and how does she know she is dealing with a barbarian?

This is an essay about how to remain a dialogical liberal when dialogical liberalism is being weaponized against you. This essay isn’t for the zealots or the trolls. It’s for those of us who believed, maybe still believe, that democracy depends on dialogue—but who are also haunted by the sense that this faith is being used against us.

Epistemically Exploitative Bullshit

I always intended to write an essay to correct the shortcomings of the original one. I regret that, for various personal reasons, I did not do so sooner. The sad truth is that a great many dialogical illiberals who are also substantively illiberal engage in esoteric communication (consciously or not). That is, their exoteric pretenses to civil, good-faith communication elide an esoteric will to domination. Sartre observed this phenomenon in the context of antisemitism, and he is worth quoting at length:

Never believe that anti‐Semites are completely unaware of the absurdity of their replies. They know that their remarks are frivolous, open to challenge. But they are amusing themselves, for it is their adversary who is obliged to use words responsibly, since he believes in words. The anti‐Semites have the right to play. They even like to play with discourse for, by giving ridiculous reasons, they discredit the seriousness of their interlocutors. They delight in acting in bad faith, since they seek not to persuade by sound argument but to intimidate and disconcert. If you press them too closely, they will abruptly fall silent, loftily indicating by some phrase that the time for argument is past. It is not that they are afraid of being convinced. They fear only to appear ridiculous or to prejudice by their embarrassment their hope of winning over some third person to their side.

If then, as we have been able to observe, the anti‐Semite is impervious to reason and to experience, it is not because his conviction is strong. Rather, his conviction is strong because he has chosen first of all to be impervious.

What Sartre says of antisemitism is true of illiberal authoritarians quite generally. Thomas Szanto has helpfully called this phenomenon “epistemically exploitative bullshit.”

One feature of epistemically exploitative bullshit that Szanto highlights is that epistemically exploitative bullshit need not be intentional. Indeed, as Sartre implies in the quote above, the ‘bad faith’ of the epistemically exploitative bullshitter involves a sort of self-deception that he may not even be consciously aware of. Indeed, most authoritarians (especially in the Trump era) are not sufficiently self-aware or intelligent enough to consciously realize that they are deceiving others about their attitude towards truth by spouting bullshit. As Henry Frankfurt observed, bullshit is different from lying in that the liar is intentionally misrepresenting the truth, but the bullshitter has no real concern for truth in the first place. Thus, many bullshiters (especially those engaged in epistemically exploitative bullshit) believe their own bullshit, often to their detriment.

However, the fact that epistemically exploitative bullshit is often unintentional, or at least not consciously intentional, creates a serious ineliminable epistemic problem for the dialogical liberal who seeks to combat it. It is quite difficult to publicly and demonstrably falsify the hypothesis that one’s interlocutor is engaging in epistemically exploitative bullshit. This often causes people who, in their heart of hearts, aspire to be epistemically virtuous dialogical liberals to misidentify their interlocutors as engaging in epistemically exploitative bullshit and contemptuously dismiss them. I, for one, have been guilty of this quite a bit in recent years, and I imagine any self-reflective reader will realize they have made this mistake as well. We will return to this epistemic difficulty in the next essay in this series.

To avoid this mistake, we must continually remind ourselves that the ascription of intention is sometimes a red herring. Epistemically exploitative bullshit is not just a problem because bullshitters intentionally weaponize it to destroy liberal democracies. It is a problem because of the social and (un)dialectical function that it plays in discourse rather than its psychological status as intentional or unintentional.

It is also worth remembering at this point that it is not just fire-breathing fascists who engage in epistemically exploitative bullshit. Many non-self-aware, not consciously political, perhaps even liberal, political actors spout epistemically exploitative bullshit as well. Consider the phenomenon of property owners—both wealthy landlords and middle-class suburbanites—who appeal to “neighborhood character” and environmental concerns to weaponize government policy for the end of protecting the economic rents they receive in the form of property values. Consider the similar phenomenon of many market incumbents, from tech CEOs in AI to healthcare executives and professionals, to sports team owners, to industrial unions, to large media companies, who all weaponize various seemingly plausible (and sometimes substantively true) economic arguments to capture the state’s regulatory apparatus. Consider how sugar, tobacco, and petrochemical companies all weaponized junk science on, respectively, obesity, cigarettes, and climate change to undermine efforts to curtail their economic activity. Almost none of these people are fire-breathing fascists, and many may believe their ideological bullshit is true and tell themselves they are helping the world by advancing their arguments.

The pervasive economic phenomenon of “bootleggers and Baptists” should remind us that an unintentional form of epistemically exploitative bullshit plays a crucial role in rent seeking all across the political spectrum. This form of bullshit is particularly hard to combat precisely because it is unintentional, but its lack of intentionality in no way lessens the harmful social and (un)dialectical functions it severe.

Despite those considerations, it is still worth distinguishing between consciously intentional forms of aggressive esotericism and more unintentional versions because they must be approached very differently. Unintentional bullshitters do not see themselves as dialogically illiberal. Therefore, responding to them with aggressive rhetorical flourishes that treat them contemptuously is very unlikely to be helpful. For this reason, the general (though defeasible) presumption that any given person spouting epistemically exploitative bullshit is not an enemy that I was trying to cultivate in the second part of this essay series still stands. In the next essay, I will address how we know when this presumption has been defeated. However, for now, let us turn our attention to the forms of epistemically exploitative bullshit common today on the right. We have now seen how epistemically exploitative bullshit can appear even in technocratic, liberal settings. But that phenomenon takes on a more virulent form when fused with authoritarian intent. This is what I call aggressive esotericism.

Aggressive Esotericism

The corrosiveness of these more ‘liberal’ and technocratic forms of epistemically exploitative bullshit discussed above, while serious, pales in comparison to more bombastically authoritarian forms of it. The truly authoritarian epistemically exploitative bullshiter aims at more than amassing wealth by capturing some limited area of state policy. While he also does that, the fascist aims at the more ambitious goal of dismantling democracy and seizing the entire apparatus of the state itself.

Let us name this more dangerous form of epistemically exploitative bullshit. Let us call this aggressive esotericism and loosely define it as the phenomenon of authoritarians weaponizing the superficial trappings of democratic conversation to elide their will to dominate others. This makes the fascistic, aggressive esotericist all the more cruel, destructive, and corrosive of society’s epistemic and political institutions.

It is worth briefly commenting on my choice of the words “aggressive esotericism” for this. The word “esoteric” in the way I am using it has its roots in Straussian scholars who argue that many philosophers in the Western tradition historically did not literally mean what their discursive prose appears to say. Esoteric here does not mean “strange,” but something closer to “hidden,” in contrast to the exoteric, surface-level meaning of the text. We need not concern ourselves with the fascinating and controversial question of whether Straussians are right to esoterically read the history of Western philosophy as they do. Instead, I am applying the general idea of a distinction between the surface level and deeper meaning of a text, the sociological problem of interpreting both the words and the deeds of certain very authoritarian political actors.

I choose the word “aggressive” to contrast with what Arthur Melzer calls “protective,” “pedagogical,” or “defensive” esotericism. In Philosophy Between the Lines Melzer argues that historically, philosophers often hid a deeper layer of meaning in their great texts. In the ancient world, Melzer argues, this was in part because they feared theoretical philosophical ideas could disintegrate social order (hence the “protective esotericism”), wanted their young students to learn how to come to philosophical truths themselves (hence the “pedagogical esotericism”), or else wanted to protect themselves from authorities for ‘corrupting the youth’ (as Socrates was accused) with their heterodox ideas.

As the modern world emerged during the Enlightenment, Melzer argues esotericism continued as philosophers such as John Locke wrote hidden messages not just for defensive reasons but to help foster liberating moral progress in society, as they had a far less pessimistic view about the role of theoretical philosophy in public life (hence their “political esotericism”). Whether Melzer is correct in his reading of the history of Western political thought need not concern us now. My claim is that many authoritarians (both right-wing Fascists and left-wing authoritarian Communists) invert this liberal Enlightenment political esotericism by engaging—both in words and in deeds, both consciously and subconsciously, and both intentionally and unintentionally—in aggressive esotericism. Hiding their esoteric will to domination behind a superficial façade of ‘rational’ argumentation.

Aggressive esotericism is a subset of the epistemically exploitative bullshit. While aggressive esotericism may be more often intentional than more technocratic forms of epistemically exploitative bullshit, it is not always so. You might realize this when you reflect on heated debates you may have had during Thanksgiving dinners with your committed Trumpist family members. Nonetheless, this lack of intention doesn’t cover up the fact that their wanton wallowing in motivated reasoning, rational ignorance, and rational irrationality has the selfish effect of empowering members of their ingroup over members of their outgroup. This directly parallels how the lack of self-awareness of the technocratic rentseeker ameliorates the dispersed economic costs on society.

Aggressive Esotericism and the Paradox of Tolerance

Even if one suspects one is encountering a true fascist, one should still have the defeasible presumption that they are a good-faith interlocutor. Nonetheless, fascists perniciously abuse this meta-discursive norm. This effect has been well-known since Popper labelled it the paradox of tolerance.

The paradox of tolerance has long been abused by dialogical illiberals on both the left and the right to undermine the ideas of free speech and toleration in an open society, legal and social norms like academic freedom and free speech, and to generally weaken the presumption of good faith we have been discussing. This, however, was far from Popper’s intention. It is worth revisiting Popper’s discussion of the Paradox of Tolerance in The Open Society and Its Enemies:

Unlimited tolerance must lead to the disappearance of tolerance. If we extend unlimited tolerance even to those who are intolerant, if we are not prepared to defend a tolerant society against the onslaught of the intolerant, then the tolerant will be destroyed, and tolerance with them. In this formulation, I do not imply, for instance, that we should always suppress the utterance of intolerant philosophies; as long as we can counter them by rational argument and keep them in check by public opinion, suppression would certainly be most unwise. But we should claim the right even to suppress them, for it may easily turn out that they are not prepared to meet us on the level of rational argument, but begin by denouncing all argument; they may forbid their followers to listen to anything as deceptive as rational argument, and teach them to answer arguments by the use of their fists. We should therefore claim, in the name of tolerance, the right not to tolerate the intolerant. We should claim that any movement preaching intolerance places itself outside the law, and we should consider incitement to intolerance and persecution as criminal, exactly as we should consider incitement to murder, or to kidnapping, or as we should consider incitement to the revival of the slave trade.

His point here is not so much to sanction State censorship of fascist ideas. Instead, his point is that there are limits to what should be tolerated. To translate this to our language earlier in the essay, he is just making the banal point that our presumption of good-faith discourse is, in fact, defeasible. The “right to tolerate the intolerant” need not manifest as legal restrictions on speech or the abandonment of norms like academic freedom. This is often a bad idea, given that state and administrative censorship creates a sort of Streisand effect that fascists can exploit by whining, “Help, help, I’m being repressed.” If you gun down the fascist messenger, you guarantee that he will be made into a saint. Further, censorship will just create a backlash as those who are not yet fully-committed Machiavellian fascists become tribally polarized against the ideas of liberal democracy. Even if Popper himself might not have been as resistant to state power as I am, there are good reasons not to use state power.

Instead, our “right to tolerate the intolerant” could be realized by fostering a strong, stigmergically evolved social stigma against fascist views. Rather than censorship, this stigma should be exercised by legally tolerating the fascists who spout their aggressively esoteric bullshit even while we strongly rebuke them. Cultivating this stigma includes not just strongly rebuking the epistemically exploitative bullshit ‘arguments’ fascists make, but exercising one’s own right to free speech and free association, reporting/exposing/boycotting those, and sentimental education with those the fascists are trying to target. Sometimes, it must include defensive violence against fascists when their epistemically exploitative bullshit manifests not just in words, but acts of aggression against their enemies.

The paradox of tolerance, as Popper saw, is not a rejection of good-faith dialogue but a recognition of its vulnerability. The fascists’ most devastating move is not to shout down discourse but to simulate it: to adopt its procedural trappings while emptying it of sincerity. What I call aggressive esotericism names this phenomenon. It is the strategic abuse of our meta-discursive presumption of good faith.

Therefore, one must be very careful to guard against mission creep in pursuing this stigmergic process of cultivating stigma in defense of toleration. As Nietzsche warned, we must be guarded against the danger that we become the monsters against whom we are fighting. I hope to discuss later in this essay series how many on the left have become such monsters. For now, let us just observe that this sort of non-state-based intolerant defense of toleration does not conceptually conflict with the defeasible presumption of good faith.

In the next part of this series, I turn to the harder question: when and how can a dialogical liberal justifiably conclude that an interlocutor is no longer operating in good faith?

You can read the whole thing here.

You can read the whole thing here.

Friedrich Hayek’s main thesis in “The Road to Serfdom” (1944) consists of postulating that attempts at central planning and dirigisme provoke, through the increasing use of political expediency, a continuous erosion of the political institutions that characterize to democracy and the separation of powers, thus leaving aside, by way of exception, constitutional rules and procedures. Hayek had warned that such a process had occurred in the Weimar Republic and pointed out that England could incur a similar process if it chose dirigisme as an instrument to overcome the post-war crisis.

Hayek himself recalled in various interviews and articles that the message of his book was rarely interpreted with due accuracy, and that, consequently, statements were attributed to him that he had never made, thus blurring the authentic gist of the work. However, this does not prevent “The Road to Serfdom” from being a classic, since, as such, it offers diverse insights as times and geographies vary, to be applied to the analysis of current events or history.

Regarding this last point, it is worth saying that the processes initiated by Argentina in 1946 -whose consequences persist to this day- and by Venezuela in 1998 -still in development today- present traits that make them different from other historical examples of how a country might take a road to serfdom. Throughout the 20th century, it was possible to verify that both the cases of dirigisme in democratic nations and the advent of totalitarian and authoritarian regimes followed profound economic crises, which were in turn consequences, directly or indirectly, of the two World Wars. On the other hand, the aforementioned experiences of Argentina and Venezuela began in quite different scenarios.

But the aim here is not to identify the historical cause of a social and political event, but only to describe a series of circumstances that condition the particular form of manifestation of a phenomenon that is essentially the same: that of dirigisme and the attempt to configure economic central planning. In most of the cases that occurred throughout the 20th century -outside of those mentioned in Argentina and Venezuela- those in charge of implementing dirigiste policies found themselves with devastated economies and societies dismantled by wars. In these situations, both economic dirigisme and the attempts at central planning of the economy acted provisionally -although in a mistaken and deficient way- as organizing principles of social and economic arrangements that were already chaotic, such as the interwar period and the first years of the postwar period. Subsequently, when in the 1970s it became evident that both economic dirigisme and central planning of the economy were yielding increasing negative net results, the different countries, whether capitalist or socialist, sought their respective ways to liberalize and decentralize their economies, which led to the economic and political processes of the 1980s and 1990s.

On the other hand, the case of Argentina in 1946, as stated, was very different. Argentina had not participated in the war and its economy was robust, despite the difficulties inherent to the international context. Similarly, Venezuela in 1998, despite having a highly discredited political class, had a prosperous economy for decades, in a very favorable international context. In these countries, economic dirigisme sought to be implemented in situations in which civil society was well structured and the private sector economic system was fully operational. Therefore, it is important to point out that both processes of increased government interference in the social and economic life of both countries were accompanied by a fracture in civil society and a growing antagonism and belligerence among different social sectors, promoted from the political system itself.

Several years after “The Road to Serfdom” (1944) was published, Hayek stated in “Rules and Order” (1973) – the first volume of “Law, Legislation and Liberty” – that a legal and political order based on respect for individual freedoms was characterized by functioning as a negative feedback system: each divergence, each conflict, each imbalance, is endogenously redirected by the legal system itself in order to maintain peace between the interactions of the different individuals with each other, defining and redefining through the judicial system -which is characterized by settling intersubjective controversies, specifying the content of the law for each specific case- the limits of the respective spheres of individual autonomy. This is how a rules-based system works, as opposed to a regime in which most decisions regarding the limits of individual freedoms are made at the discretion of government authorities.

Given that the 20th century mostly offered examples of societies devastated by war, pending reconstruction, perhaps we have lost sight of the effects of economic dirigisme and attempts at central planning of the economy on Nealthy civil societies and fully functioning economies. The cases of the processes initiated by Argentina in 1946 and by Venezuela in 1998 call to think about what their consequences could be for societies with economies with a moderately satisfactory performance. Among these consequences, there will surely be a growing social polarization, in which the different sectors demand their respective participation in the discretionary redistribution of income. These situations therefore acquire the dynamics inherent to positive feedback systems, in which social belligerence escalates and demands increasing levels of government interference and authoritarianism. This is another aspect of the road to serfdom that should begin to be considered in the 21st century.

Several years ago, a mentor shared Paul Graham’s 2008 essay ‘Cities and ambition’ as part of helping me evaluate where to pursue my doctorate. Graham’s argument is that cities act like a peer group on an individual: where one lives affects one’s goals, sense of individuality, and ambition. Therefore, one should choose where to live carefully, just as one should choose one’s friends carefully.

Graham pointed out that a city is not only a geographic location, an administrative area, or a convenient location. A city is a collection of individuals who form a group. Groups in turn have a culture, a mentality, a way of doing things. As Graham described it, “[O]ne of the exhilarating things about coming back to Cambridge every spring is walking through the streets at dusk, when you can see into the houses. When you walk through Palo Alto in the evening, you see nothing but the blue glow of TVs. In Cambridge [Massachusetts, the home of Harvard and MIT] you see shelves full of promising-looking books.” Following on Graham’s essay, I propose an additional metric for evaluating a city: the contents of its second-hand bookshops.

When I travel, inevitably I wash up in at least one used bookstore. Sometimes they are independent establishments, sometimes they are specialist stores focused on collectors, sometimes they’re big chains, such as Half Price Books. Like a weathervane, second-hand bookshops point to the state of a city’s intellectual and cultural life.

Big cities, such as New York, Paris, Vienna, or Washington, D.C., have a wide array of types of second-hand bookstores. Generally, one can find a suitably catholic selection: Israel Joshua Singer lives in the same space as Olivia Butler, R. F. Kuang, William Faulkner, or Kingsley Amis. At a level above or below one can find copies of old translations of the Zohar or the Buddhist sutras along with crumbling copies of the Douay-Rheims Bible. What one will probably not find are volumes of esoteric slogans with saccharine cover designs from which religious symbolism is carefully excluded, even if the books are filed under “Christianity.”

A recent visit to St. Louis, a city which despite its problems has a lovely art museum that was buzzing with activity on its free access day (every Friday), led to the requisite visit to a small, second-hand bookstore. It was a charmingly simple establishment but rich with selection. After admiring the contrast between the display of books from the “Childhood of Famous Americans” children’s series placed near Ta-Nehisi Coates’ books, I came away with several volumes of Stefan Zweig’s essays in the original German.

In contrast, a visit to the Half Price Books in a college city which hosts the flagship state university was almost futile. A single volume of Olivia Butler sat alone amongst mishmash of fantasy books. Poetry was non-existent in the poetry section, excluding a college textbook edition of excerpts of Homer. The jewel of the literature section was an incomplete paperback set of Winston Graham’s Poldark series, with covers alluding to the derivative television show. The foreign language section had no books in French, German, or Italian, excluding dictionaries and outdated textbooks, and the Japanese subdivision had only children’s books. Translations of popular manga don’t count toward foreign language credit in such establishments. A request for the writings of Epictetus turned up nothing in the system, but several cartoon books of witches’ spells were prominently displayed at the entrance of the religion and philosophy section. The young adult section overflowed with cheap vampire romances, a fitting start for what was in the more advanced reading sections. Based on the detritus of current residents’ reading, the prognosis for intellectual or cultural life is not good for this college town.

During my long traveling over Europe this summer, among other areas, I ventured to Albania, a country where houses frequently do not have numbers and where I located the building where a friend of my youth now lives by a drawing on a gate. This is a country where the so-called oriental bazaar is buzzing everywhere, where towns literally hang on cliffs, and where one easily runs across the ruins of the Roman, Byzantine, and Ottoman legacy of the country and the “archaeology” of the recent communist past (small concrete family bunkers, tunnels for the former communist nomenklatura, monumental sculptures and mosaics in the socialist realism style).

It was interesting to see how this country, which lived much of the 20th century under the most vicious communist dictatorship (1944-1990), is now trying to live a normal life. To some extent, Albania is very similar to present-day Russia: decades of the negative natural selection under communism killed much of self-reliance, individual initiative, and produced the populace that looks up to the government for the solutions of their problems. For the past thirty years, a new generation emerged, and things did dramatically change. Yet, very much like in Russia, much of the populace feels nostalgia for the “good” old days, which is natural.

According to opinion polls, 46% of the people are nostalgic for the developed communism of dictator Enver Hoxha (1944-1985), an Albanian Stalin, and 43% are against communism; the later number should be higher, given the fact that many enterprising Albanians (1/4 of the population) live and work abroad. During the last decades of its existence, Albanian communism slipped into a wild isolationism of the North Korean style. Except for Northern Korea and Romania, all countries, from the United States, Germany, UK (capitalist hyenas) to the USSR, China, and Yugoslavia (traitors to socialism), were considered enemies. Incidentally, Albanian communism was much darker and tougher than the Brezhnev-era USSR. Nevertheless, as it naturally happened in Russia and some other countries, in thirty years, the memory of a part of the population laundered and cleansed the communist past, and this memory now paints this past as a paradise, where everyone was happy and looked confidently into the future, where secret police and labor concentration camps existed for a good reason, and where the vengeful dictator appears as a caring father.

In the hectic transition to market economy and with the lack of established judicial system, there naturally emerged a widespread corruption, nepotism. But, at the same time, small business somehow flourishes. The masses and elites of the country aspire to be united with neighboring Kosovo since both countries are populated by Albanian majorities. On top of this, Kosovo is the birthplace of Albanian nationalism. However, unlike current Russia, which is spoiled with abundant oil and gas resources (the notorious resource curse factor), corrupt Albanian bureaucrats that rule over a small country exercise caution. Although that small country is too blessed with oil, natural gas, chromium, copper, and iron-nickel, they do not waste their resources on sponsoring geopolitical ventures and harassing their neighbors. For themselves, the Albanians resolved the Kosovo issue as follows: we will be administratively two different states, but de facto economically and socially we will be tied to each other, and all this makes life easier for people, preventing any conflicts. Not a small factor is that, unlike, for example, Russia or Turkey, Albanian nationalism is devoid of any imperial syndromes, and therefore there is no nostalgia for any glorious lost empire. The fact that Albania is a member of NATO also plays a significant role, which forces the Albanian elites behave. Acting smartly, instead of geopolitical games, they decided to fully invest in the development of the tourism business, believing that, in addition to mining their resources, this is the best development option.

“Young man, what we meant in going for those Redcoats was this: we had always governed ourselves and we always meant to. They didn’t mean we should.”

First of all, thanks to anyone who read my post on the deleted clause of the Declaration of Independence. I see many more readers around today every year, and I think that it serves as a constant reminder that our Founders were not a uniform group of morally perfect heroes, but a cobbled-together meeting of disagreeable risk-takers who were all dedicated to ‘freedom’ but struggled to agree on what it meant.

However, as we all get fat and blind celebrating the bravery of the 56 men putting who put pen to paper, I also want to call out the oft-forgotten history of rebellion that preceded this auspicious day. July 4th, 1776 makes such a simple story of Independence that we often overlook the men and women who risked (and many who lost) their lives, fortunes, and sacred honor to make that signing possible, and who kept the flame of rebellion alive when it was most likely to be snuffed out.

This inspired me to collate some of the most important early moments and individuals on whom fate turned. I’m deliberately skipping some well known icons and events (the Boston Massacre and Tea Party, the first shot on Lexington Green, etc.), but if you want to see the whole tapestry and not just the forgotten images, I recommend the following Founding Trilogy:

I owe my knowledge and the stories below to these histories that truly put you among the tiny communities that fought before July 4th, and they have convinced me, there is no Declaration, no Revolution, and no United States of America without the independent actions and decisions of their central cast.

Part I: Before the Ride

Paul Revere’s ride is one of the most mythologized, and mis-cast, moments in history. As early as the day after the Battle of Lexington and Concord, local Whigs were intent on casting the battle as an unprovoked attack by the tyrannical British occupiers and their imperious leader in Boston, General (and Governor) Thomas Gage. That meant that they brushed possibly the most important aspect of the rebellion’s early success under the rug, and honored Revere for his rapid responsiveness on that very night. Since then, unfortunately, the ride has been the center of most messaging honoring or criticizing this patriot.

Revere’s ride would have been useless if, for several years, he had not been New England’s most active community organizer. The battle did not represent the first time Thomas Gage secretly marched on the powder stores of small New England towns (he had successfully done so to Somerville in 1774), or even the first time Boston’s suburbs were called to arms in response (in the Powder Alarm, thousands turned out to defend against a false-alarm gunpowder raid). Revere’s real contribution was that he was one of many go-betweens for small towns intent on protecting their freedom and their guns, and their link to the conspirators led by Sam Adams and John Hancock in Boston. He helped spawn a network of communication, intelligence, and purchase of arms that was built on New England’s uniquely localized community leadership, without which it would have been impossible for over 4,000 revolutionaries to show up, armed and organized, on the road from Concord to Boston, in less than 8 hours.

New England towns had some of the most uniquely localized leadership in the history of political organization. In these small, prosperous towns, with churches as their center of social organization, government was effectively limited to organizing defense, mostly in the purchase of cannon and gunpowder, both of which were rare in the colonies. The towns also mustered and drilled, and while most towns did not have centralized budgets, they honored wealthier citizens who would donate guns to those who could not afford their own. From town government to General Gage’s seizures to the early supply conflicts, then, guns and especially gunpowder (which was not manufactured anywhere in New England in 1775, and rapidly became the scarcest resource of the early Revolution) were literally the center of town government and the central reason underlying the spark and growth of Revolution.

The Whigs (or Patriots) could have, in fact, just as easily noted December 14th, 1774, as the kick-off of the Revolution, since it was the first military conflict between Patriots and British garrisons, centered around gunpowder and cannon. On that day, the ever-present Revere, having learned that Gage may attempt to seize the powder of Portsmouth, NH, rode to warn John Langdon, who organized several hundred men not only to defend the town’s powder but to seize Fort William and Mary. He led several hundred Patriots to the fort, on the strategic Newcastle Island at the mouth of the Portsmouth River, and after asking the six British soldiers garrisoning the fort to surrender, stormed it in the face of cannonfire. No deaths resulted, and more Patriots arrived the next day, stealing a march on Gage and driving him to see his Boston post as a tender toehold in a territory alight with spies, traitors, and rebels.

However, despite the fact that the British governor of New Hampshire fled and the British never regained the territory, December 14th is not our Independence Day. Even though it was a successful pre-Lexington battle, defending the same rights, and resulting from a ride of Paul Revere, it has been largely overshadowed. Is it because it was an attack by Patriots, undermining the ‘innocent townsfolk’ myth of Patriot propaganda? Because no one died for freedom? Because American historians like to remember symbolic signatures by fancy Congresses rather than the trigger fingers of rural nobodies? Either way, December 14th shows that the gunpowder-centric small town networks, and their greatest community organizer, were the kindling, the flint, and the steel of the Revolution, and were all ready to spark long before Lexington Green.

Even the events that led to that fateful battle center around a few key organizers and intelligence operatives. Hancock and Adams were only the most publicly known of hundreds of hidden leaders, and lacking the space to recognize all, I’ll just recognize Dr. Joseph Warren, who asked Revere to make his famous ride and who served as President of the Provincial Congress until he was killed in the desperate fighting on Bunker Hill, and Margaret Kemble Gage, who despite being married to General Gage favored the Whigs likely leaked his secret plans to march on Concord, and was subsequently forced to sail to Britain by her husband, probably to stop her role as the Revolution’s key spy.

These key figures put their lives on the line not for their country, nor for the political philosophies of classic liberalism, nor even because of the ‘oppressive’ Stamp Act or Intolerable Acts, but to defend their own and their community’s visceral freedoms from seizures and suppression by Gage’s men. They were joined by thousands of otherwise-nobodies who jumped out of bed to defend their neighbors, whose motivations are best captured by the quote above by Levi Preston, the longest-lived veteran of Lexington and Concord. The full quote, given to a historian asking about the context for the battle in 1842, is revealing:

Chamberlain (historian): “Captain Preston, why did you go to the Concord Fight, the 19th of April, 1775?”

Preston didn’t answer.

Chamberlain: “Was it because of the Intolerable Oppressions?”

Preston: “I never felt them.”

What of the Stamp Act?

Preston: “I never saw one of those stamps.” he responded.

Tea Tax?

Preston: “I never drank a drop of the stuff…The boys threw it all overboard.”

Chamberlain: “Maybe it was the words of Harrington, Sydney or Locke?”

Preston: “Never heard of ‘em,”

Chamberlain: “Well, then, what was the matter? And what did you mean in going to the fight?”

Preston: “Young man, what we meant in going for those Redcoats was this: we always had governed ourselves, and we always meant to. They didn’t mean we should.”

“And that, gentlemen,” Chamberlain resolved in his history, “is the ultimate philosophy of the American Revolution.”

I spotted two Bald Eagles today in Cincinnati, which is really fitting for the Fourth of July. The two Bald Eagles—one indolent and one vigilant—capture not only the attitudes of two influential figures in American politics about this national symbol that was hotly debated till 1789, but they also reflect the fractured character of these United States.

You probably already know that Benjamin Franklin was an outspoken detractor of the bald eagle. He stated his disinterest in the national symbol in a letter to a friend:

“I wish the bald eagle had not been chosen as the representative of our country; he is a bird of bad moral character; like those among men who live by sharping and robbing, he is generally poor, and often very lousy. The turkey is a much more respectable bird and withal a true, original native of America.”

In contrast, President John F. Kennedy wrote to the Audubon Society:

“The Founding Fathers made an appropriate choice when they selected the bald eagle as the emblem of the nation. The fierce beauty and proud independence of this great bird aptly symbolizes the strength and freedom of America. But as latter-day citizens we shall fail our trust if we permit the eagle to disappear.”

The two Bald Eagles, which symbolize, in my estimation, two divergent historical viewpoints, show us that American history is splintered into sharp conceptions of the past as it has been politicizedly revised to forge a more perfect union. There is little question that the tendency toward seeking out varied intellectual interpretations of US history is unabating and maybe essential to the growth of a mature republic. On holidays like the Fourth of July, however, a modicum of romanticism of the past is also required if revisionist histories make it harder and harder for the average person to develop a classicist vision of the Republic as a good—if not perfect—union and make it seem like a simple-minded theory.

The two Bald Eagles aren’t just symbolic of the past; they also stand for partisanship and apathy in the present toward issues like inflation, NATO strategy, Roe v. Wade, and a variety of other divisive concerns. In addition, I learned there is an unfortunate debate on whether to have a 4th of July concert without hearing the 1812 Overture. For those who are not familiar, it is a musical composition by the Russian composer Tchaikovsky that has become a staple for July 4th events since 1976.

In view of this divisiveness here is my unsophisticated theory of American unity for the present moment: Although the rhetoric of entrenched divisiveness and the rage of political factions—against internal conflicts and international relations—are not silenced by the Fourth of July fireworks, the accompanying music, festivities, and the promise of harmony, they do present a forceful antidote to both. So why have a double mind on a national ritual that serves as a unifying force and one of the few restraints on partisanship? Despite the fact that I am a resident alien, I propose preserving Tchaikovsky’s 1812 Overture, arousing the inner dozing Bald Eagle, and making an effort to reunite the divided attitude toward all challenges. The aim, in my opinion, should be to manifest what Publius calls in Federalist 63 the “cool and deliberate sense of community.”

An Address on Liberty (Deirdre McCloskey)

As usual, insightful and educational.

Much of our life is governed neither by the government’s laws or by solely individual fancies, but by

following or resisting or riding spontaneous orders.

The speech also references Harrison Bergeron, the short story by Kurt Vonnegut, Jr. (published in 1961), which NOL treated few years ago. I have to admit, I only knew the author’s name and no more. The opening is quite something:

THE YEAR WAS 2081, and everybody was finally equal. They weren’t only equal before God and the law. They were equal every which way. Nobody was smarter than anybody else. Nobody was better looking than anybody else. Nobody was stronger or quicker than anybody else. All this equality was due to the 211th, 212th, and 213th Amendments to the Constitution, and to the unceasing vigilance of agents of the United States Handicapper General.

This absurd world drips vitriol, though the target is debatable: Most see a parody of socialistic/ communistic principles, though others think that the irony was intended to the (Cold War) US perception of those principles. Also: What’s this thing with dystopias and April?

Vonnegut is the second-in-a-row author from that era that I added to my list, after the recent discovery of Frederik Pohl (just acquired The Space Merchants, written with Cyril M. Kornbluth, in a decadent 90s Greek version).

(H/T to Cafe Hayek for the McCloskey link, and Skyclad for the title word play).

Today’s food-for-thought menu includes Eco-Feminism, Indics of Afghanistan, the Fetus Problem, a Mennonite Wedding, the Post-Roe Era, and the Native New World. I’m confident the dishes served today will stimulate your moral taste buds, and your gut instincts will motivate you to examine these themes in greater depth.

Note: I understand that most of us are unwilling to seek the opposing viewpoint on any topic. Our personal opinions are a fundamental principle that will not be altered. However, underlying this fundamental principle is our natural proclivity to prefer some moral taste buds over others. This series represents my approach to exploring our natural tendencies and uncovering different viewpoints on the same themes without doubting the validity of one’s own fundamental convictions. As a result, I invite you to reorder the articles I’ve shared today using moral taste buds that better reflect your convictions about understanding these issues. For instance, an article that appeals to my Care/Harm taste bud may appeal to your Liberty/Oppression taste bud. This moral divergence reveals different ways to look at the same thing.

The Care/Harm Taste Bud: Eco-feminism: Roots in Ancient Hindu Philosophy

The Nature-Culture Conflict Paradigm today reigns supreme and seeks to eradicate cultures, societies, and institutions that advocate for and spread the Nature-Culture Continuum Paradigm. Do you see this conflict happening? If so, can you better care for the environment by adopting a Nature-Culture Continuum paradigm? Is there anything one may learn from Hindu philosophy in this regard?

The Fairness/Cheating Taste Bud: 9/11 FAMILIES AND OTHERS CALL ON BIDEN TO CONFRONT AFGHAN HUMANITARIAN CRISIS

Due to a focus on other issues in Afghanistan, such as terrorism, food and water shortages, and poverty, the persecution of religious minorities in the nation is not as generally known, despite the fact that it has been a human rights crisis for decades. Ignorance of this topic poses a serious risk to persecuted groups seeking protection overseas. Western governments have yet to fully appreciate the risks that Afghan Sikhs and Hindus endure. I also recommend this quick overview of the topic: 5 things to know about Hindus and Sikhs in Afghanistan.

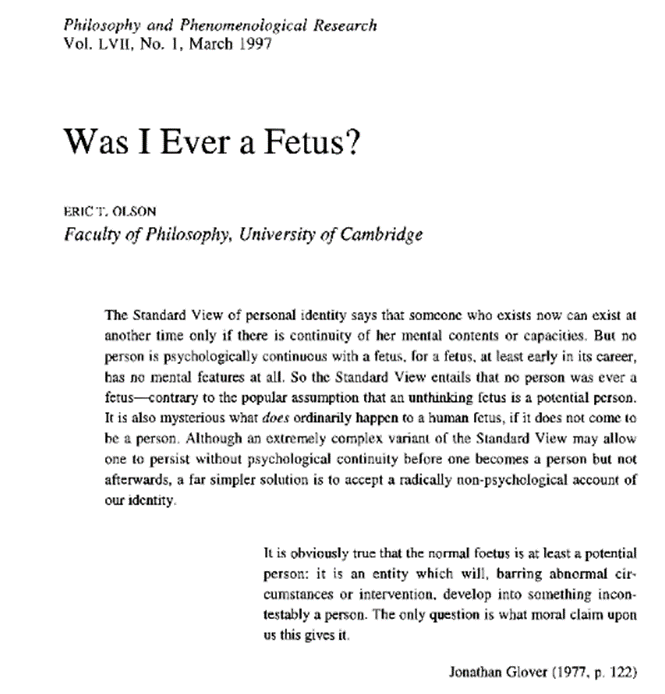

The Liberty/Oppression Taste Bud: Biological Individuality and the Foetus Problem

As I’ve discovered, abortion was one of the earliest medical specialties in American history when it became entirely commercialized in the 1840s. As a result, the United States has been wrestling with moral issues about abortion for 182 years! The abortion debate has gone through rights-based assertions and advanced to claims about the policy costs and benefits of abortion and now appears to have returned to rights-based arguments in the last 50 years. Regardless of where you stand on this debate, this much is clear: in the U.S., the circle of moral quandary surrounding abortion never closes. Nevertheless, what is the source of the moral ambiguity surrounding abortion? Can the philosophy of biology help us better comprehend this moral quandary?

Some philosophers would argue that the issue of biological individuality is central to this moral dispute. But why is biological individuality even a point of contention? Counting biologically individual organisms like humans and dogs appears straightforward at first glance, but the biological world is packed with challenges. For instance, Aspen trees appear to be different biological units from above the ground; nonetheless, they all share the same genome and are linked beneath the ground by a sophisticated root system. So, should we regard each tree as a distinct thing in its own right or as organs or portions of a larger organism?

Similarly, humans are hosts to a great variety of gut bacteria that play essential roles in many biological activities, including the immune system, metabolism, and digestion. Should we regard these microorganisms as part of us, despite their genetic differences, and treat a human being and its germs as a single biological unit?

Answers to the ‘Problem of Biological Individuality’ have generally taken two main approaches: the Physiological Approach, which appeals to physiological processes such as immunological interactions, and the Evolutionary Approach, which appeals to the theory of evolution by natural selection. The Physiological Approach is concerned with biological individuals who are physiological wholes [Human + gut bacteria = one physiological whole], whereas the Evolutionary Approach is concerned with biological individuals who are selection units [Human and gut bacteria = two distinct natural selection units].

Is a fetus an Evolutionary individual or a Physiological individual? If we are Evolutionary individuals, we came into being before birth; if we are Physiological individuals, we come into being after birth. While the Physiological Approach makes it evident that a fetus is a part of its mother, the Evolutionary Approach makes it far less clear. But is there an overarching metaphysical approach to solving the problem of biological individuality? Can metaphysics (rather than organized monotheistic religion) lead us to a pluralistic zone where we can accept both perspectives with some measure of doubt?

The Loyalty/Betrayal Taste Bud: What I Found at a Mennonite Wedding

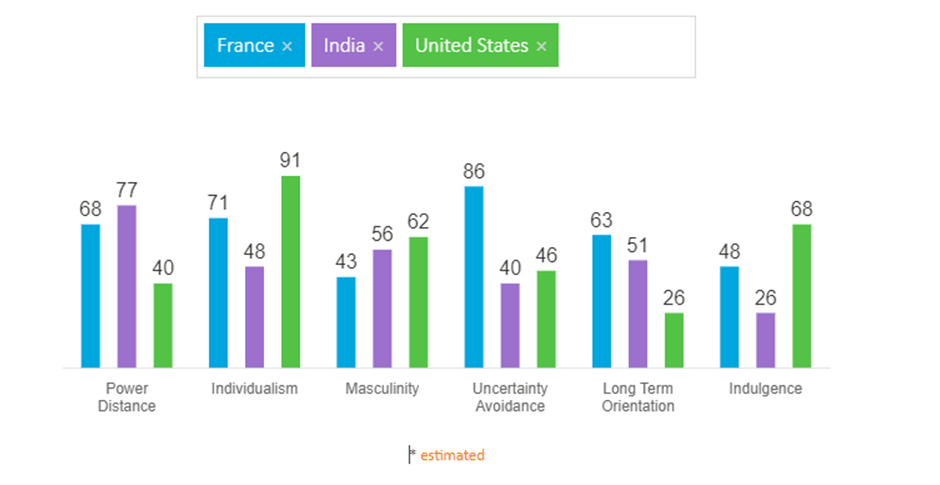

Do you consider the United States to be a high-power-distance or low-power-distance culture? Coming from India, I used to see the U.S. as the latter, but in the last 12 years of living here, it is increasingly becoming the former.

Does your proximity to an authority strengthen or lessen your loyalty?

The Authority/Subversion Taste Bud: The Post-Roe Era Begins Political and practical questions in an America without a constitutional right to abortion.

[In the link above, make sure to listen to both Akhil Amar and Caitlin Flanagan]

I also recommend reading Why Other Fundamental Rights Are Safe (At Least for Now)

Is there a flaw in the mainstream discussion of the U.S. Constitution that the abortion debate has brought to light? In my opinion, although predating the U.S. federal constitution and being significantly more involved in federal politics and constitutional evolution, each American state’s constitution is widely ignored. Keep in mind that state constitutions in the United States are far more open to public pressure. They frequently serve as a pressure release valve and a ‘pressuring lever’ for fractious U.S. national politics, catalyzing policy change. Regrettably, in an era of more contentious national politics, mainstream U.S. discourse largely ignores changes to state constitutions and spends far too much time intensely debating the praise or ridicule the federal Constitution receives for specific clauses, by which time the individual states have already shaped how the nation’s legal framework should perceive them. Altogether, a federal system, where individual state constitutions are ignored, and conflicts are centralized, is the American political equivalent of Yudhishthira’s response to the world’s greatest wonder in the thirty-three Yaksha Prashna [33 questions posed by an Indic tutelary spirit to the perfect king in the Hindu epic of Mahabharata].

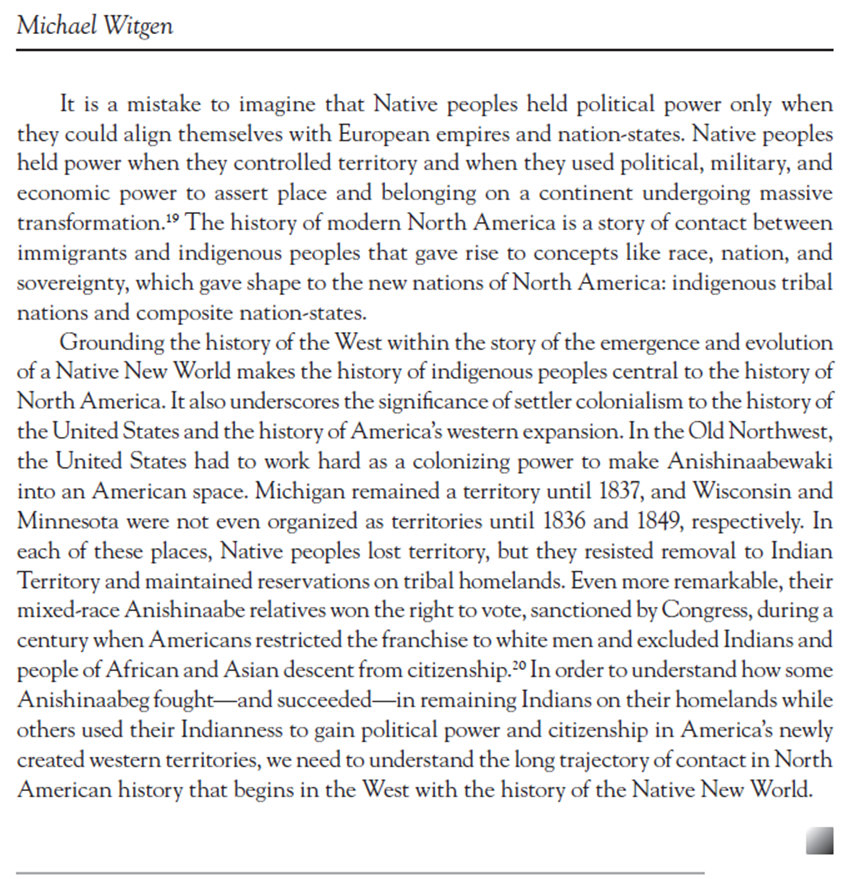

The Sanctity/Degradation Taste Bud: The Native New World and Western North America

The emergence of a distinctly Native New World is a founding story that has largely gone unrecorded in accounts of early America. Here’s an excerpt from the article:

To round off this edition, a Western movie question: Are there any examples of American Westerns developed with the opposing premise—valuing the First Nation’s People’s agency, which has gained historical support? Why not have a heroic Old World First Nation protagonist who safeguards indigenous practices and familial networks in a culturally diverse middle ground somewhere in the frontier country, shaping and influencing the emerging New World? Can this alternate perspective revitalize the jaded American Western movie genre?

[Here’s the previous edition of Stimuli For Your Moral Taste Buds]

2s rhyme nicely with 7s

Academic papers are a tough nut to crack. Apart from the prerequisite of expertise in the field (acquired or ongoing, real or imaginary), there is some ritualistic, innuendo stuff, like the author list. I always keep in mind this strip from PHD Comics:

It came handy when MR suggested this paper, A Golden Opportunity: The Gold Rush, Entrepreneurship and Culture.

Now, I cannot even pretend I read the thing. But eight listed authors popped-up to my eyes. And the subject is catchy enough in cementing the hard way what may seem as a pretty evident proposition

The term “Argonauts” (used for the gold rushers of 1849) irked me somewhat at first, since the crew of legendary, talking ship Argo was an all-star Fellowship of Justice Avengers team, featuring the baddest champions around (warfare, navigation, pugilism, wrestling, horse riding, music, to note the most renown, some of them later fathered other heroes), human or demi-god. But there is a sad story behind it, and also the Greek myth can be understood as a parable for ancient gold hunting, so I indeed learned something (on-top of quit charging to the void without good reason).

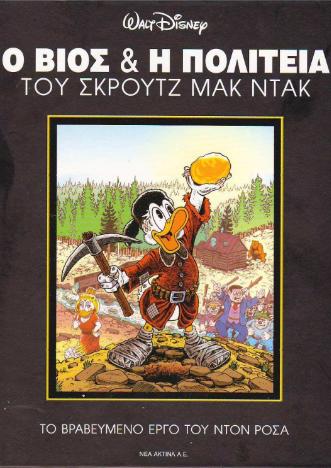

Argonautica notwithstanding, there is an even more telling reference for the theme of the paper. That would be no other than Scrooge McDuck, the creation of Carl Barks, the richest duck in the world. Per his biography, a gravely underappreciated graphic nov comic book (originally a series of twelve stories, published thirty years ago, other stories were added as a Companion edition later) that frustratingly keeps falling off best-of lists (I mean, apparently there is So MucH DePtH in costumed clowns, but not in anthropomorphic animals without pants) he was a gold rusher AND and an entrepreneur extraordinaire. The book, The Life and Times of Scrooge McDuck by Don Rosa, tells Scrooge’s life before his first official appearance as a depressed old recluse who meets his estranged nephews in Christmas 1947. The duck adventures we all are familiar with followed that meeting. Rosa collected all the smatterings of Scrooge’s past from these endeavors, memories, quotes, thoughts, and reconstructed a working timeline (with the inevitable and necessary artist’s liberty, of course). The resulting prequel is all the more impressive given the sheer volume of detail, the breezy rhythm and the context it gives to a deserving character.

According to the Life and Times, Scrooge struggled from child’s age. The Number One Dime was not “Lucky”, it was earned by polishing boots. It deliberately was a lowly US coin (instead of the expected Scottish one), by a well-meaning ploy to inform young Scrooge that there are cheaters about. It was this underwhelming payment for tough work that lead him to drop this signature line and decide on how to conduct his business:

Well, I’ll be tougher than the toughies and sharper than the sharpies — and I’ll make my money square!

Scrooge McDuck, The Last of the Clan McDuck

This fist “fail” was followed by a series of entrepreneurial tries, each failing and each teaching our hero a lesson. Scrooge moved to the US to join as a deckhand, and then as a captain, a steamboat just as railroads were picking up. His cowboy and gun slinging chops went down the drain when the expansion to the West ended. He rose, fell, and still kept coming back. He became rich in the Klondike Gold Rush in 1897, 20 years after the Number One Dime affair (and a little late for the California Gold Rush, my bad).

As the paper technically puts it, the personality traits of those involved in gold prospecting associated with openness (resourceful, innovative, curious), conscientiousness (hardworking, persistent, cautious) and emotional stability (even-tempered, steady, confident), underpinned by low risk aversion, low fear of failure and self-efficacy. This constellation of traits, the authors note, is consistently associated with entrepreneurial activity. Indeed, from that point Scrooge demonstrated considerable acumen and expanded his business across industries and countries. A trait that serves him in building and maintaining his wealth (and seems lacking in his peers) is prudence (perceived as stinginess) and a very laconic lifestyle.

He casually brawled and stood his ground against scum. His undisputable morals lapsed only once, when ruthlessness briefly overtook decency. Though he made amends and corrected course, this failing, coupled with a hard demeanor, made his family distance themselves from him, adding a tragic – and very humane – edge to the duck mogul.

The hero, “born” 155 years ago (8 Jul 1867), stands as an underrated icon of individual effort and ethics.

Based on anthropologist Richard Shweder’s ideas, Jonathan Haidt and Craig Joseph developed the theory that humans have six basic moral modules that are elaborated in varying degrees over culture and time. The six modules characterized by Haidt as a “tongue with six taste receptors” are Care/harm, Fairness/cheating, Loyalty/betrayal, Authority/subversion, Sanctity/degradation, and Liberty/oppression. I thought it would be interesting to organize articles I read into these six moral taste buds and post them here as a blog of varied reading suggestions to stimulate conversation not just on various themes but also on how they may affect our moral taste buds in different ways. To some of you, an article that appeals to my Fairness taste bud may appeal to your taste bud on Authority.

I had planned to post this blog yesterday, but it got delayed. Today, I can’t write a blog without mentioning guns. Given that gun violence is a preventable public health tragedy, which moral taste bud do you favor when considering gun violence? Care and Fairness taste buds are important to me.

I’ve only ever been a parent in the United States, where gun violence is a feature rather than a bug, and my childhood in India has provided no context for this feature. But, I can say that India has not provided me with reference points for several other cultural features that I can embrace, with the exception of this country’s gun culture. It is one aspect of American culture that most foreign nationals, including resident aliens like myself, find difficult to grasp, regardless of how long you have lived here. I’d like to see a cultural shift that views gun ownership as unsettling and undesirable. I know it is wishful thinking, but aren’t irrational ideas salvation by imagination?

Though I’m not an expert on guns and conflict, I can think broadly using two general arguments on deterrence, namely:

A) The general argument in favor of expanding civilian gun ownership is that it deters violence at the local level.

B) The general case for countries acquiring nuclear weapons is that it deters the escalation of international conflict.

I sense an instinctual contradiction when A) and B) are linked to the United States. The US favors a martial culture based on deterrence by expanding civilian gun ownership within its borders while actively preventing the same concept of deterrence from taking hold on a global scale with nuclear weapons. Why? The US understands that rogue states lacking credible checks and balances can harm the international community by abusing nuclear power. Surprisingly, this concept of controlling nuclear ammunition is not effectively translated when it comes to domestic firearms control. I get that trying to maintain a global monopoly on nuclear weapons appeals to the Authority taste bud, but does expanding firearms domestically in the face of an endless spiral of tragedies appeal just to the Liberty taste bud? Where are your Care and Fairness taste buds languishing?

Care: The Compassionate Invisibilization Of Homelessness: Where Revanchist And Supportive City Policies Meet/ Liberal US Cities Including Portland Change Course, Now Clearing Homeless Camps

[I’m sharing these two articles because my recent trip to Portland, Oregon, revealed some truly disturbing civic tragedies hidden within a sphere of natural wonders. I hadn’t expected such a high rate of homelessness. It’s a shame. “Rent control does not control the rent,” Thomas Sowell accurately asserts.]

Fairness: America Has Never Really Understood India

[I’d like to highlight one example of how “rules-based order” affected India: In the 1960s, India faced a severe food shortage and became heavily reliant on US food aid. Nehru had just died, and his successor, Prime Minister Lal Bahadur Shastri, called upon the nation to skip at least one meal per week! Soon after, Shastri died, and Prime Minister Indira Gandhi took over, only to be humiliated by US President Lyndon B. Johnson for becoming dependent on food aid from his country. The progressive US President was irked by India’s lack of support for his Vietnam policy. So he vowed to keep India on a “ship-to-mouth” policy, whereby he would release ships carrying food grain only after food shortages reached a point of desperation. Never to face this kind of humiliation, India shifted from its previous institutional approach to agricultural policy to one based on technology and remunerative prices for farmers. The Green Revolution began, and India achieved self-sufficiency. The harsh lesson, however, remains: in international relations, India is better off being skeptical of self-congratulatory labels like “leader of the free world,” “do-gooders,” “progressives,” and so on.]

Liberty: Can Islam Be Liberal? / Where Islam And Reason Meet

[I would like to add that, in the name of advocating liberalism for all, personal liberty is often emphasized over collectivist rights in the majority, while collectivist rights are allowed to take precedence over personal liberty in minority groups, and all religious communities suffer as a result.]

Loyalty: Black-Robed Reactionaries: Has The Supreme Court Been Bad For The American Republic?

[Is it all about Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Supreme Court Majority?]

Authority: How Curing Aging Could Help Progress

[In my opinion, the indefinite future that awaits us compels us to contextualize our current activities and lives. What do you think will happen if anti-aging technology advances beyond the limits of our evolutionary environment? Furthermore, according to demographer James Vaupel, medical science has already unintentionally delayed the average person’s aging process by ten years [Vaupel, James W. “Biodemography of human ageing.” Nature 464.7288 (2010): 536-542]. We have 10 extra years of mobility compared to people living in the nineteenth century; 10 extra years without heart disease, stroke, or dementia; and 10 years of subjectively feeling healthy.]

Sanctity: India and the Indian: Hinduism, Caste Act As Unifying Forces In The Country

[Here is my gaze-reversal on caste as a moderate Hindu looking at a complacent American society: If caste is a social division or sorting based on wealth, inherited rank or privilege, or profession, then it exists in almost every nation or culture. Regardless of religious affiliation, there is an undeniable sorting of American society based on the intense matching of people based on wealth, political ideology, and education. These “American castes,” not without racial or ethnic animus, organize people according to education, income, and social class, resulting in more intense sorting along political lines. As a result, Democrats and Republicans are more likely to live in different neighborhoods and marry among themselves, which is reflected in increased polarization in Congress and perpetual governmental gridlock. The intensification of “American castes,” in my opinion, is to blame for much of the political polarization. What is the United States doing about these castes? Don’t tell me that developing more identity-centered political movements will solve it.]

I intend to regularly blog under this heading. To be clear, I refer to regularly using the Liberty taste bud rather than Fairness.