Year: 2017

Coup and Counter Coup in Turkey (first of a series of posts on Turkey since 15th July 2016 and background topics)

On July 15th 2016, a group of army officers up to at least the Brigadier General (one star general) level attempted to seize control of the Turkish state. On the morning of the 20th it was evident that the coup had collapsed though the government, along with its allies in the media, social media, think tanks and so on was eager to promote the idea of an unended coup which might spring back into life, like the villain in a horror film, at any moment over a long indefinite period of time. No follow-up coup materialised. The most that can be said for that unending coup mentality was that it is difficult to know how much of the army would have gone over if the coup organisation had captured or killed President Erdoğan. What the never-ending coup claims achieved was to legitimise and mobilise paranoia, intolerance, and authoritarian state reactions with regard to anyone who might be in opposition to the Erdogan/Justice and Development Party (AKP) government.

The overwhelming feeling among government supporters and opponents on the 21st was that the coup was instigated by followers of Fetullah Gülen, a religious leader who went into exile before the AKP came to power in 2002. His followers control an international network of businesses, banks, schools, and media organisations. They carefully targeted the most sensitive areas of state employment in Turkey with the goal of creating a Gülenist dominated state and were aided in this enterprise by the AKP governments who wanted a network to rival the ‘Kemalists’, relatively secular people in the state, business, media, and educational sectors. Their relationship broke down in 2013 for reasons which are inevitably obscure at present, but appear to arise from the conflicting extreme ambitions for absolute power on both sides.

The coup may have been joined by Kemalists and the coup organisers gestured towards this position when a television announcement proclaimed that the coup council name referred to a well-known slogan of Kemal Atatürk, ‘Peace at home, peace in the world’. Kemalism of course refers to the ideology of secularist nationalist republicanism endorsed by Kemal Atatürk, the founder of the Republic of Turkey. I will return to this topic in a later post, but in brief Kemalism of some kind – and there are many kinds and many grey areas – was the dominant influence in the army and allied parts of the state until recently. It is roughly analogous to the Jacobin tradition in France and in the same way has referred both to popular sovereignty and vanguardism. There are some who promoted the idea in the past that Kemalism was the problem and the AKP was the solution, and they are having difficulty in not seeing the 15th July Coup attempt as at least a Gülenist-Kemalist partnership. However, there is no evidence that Kemalists participated in any more than an individual ad hoc basis. Indeed after the 15th, retired generals associated with Kemalism were called back into service, in a process which now seems to have ended Kemalist sympathy for Erdoğan as a bulwark against the Gülenists and the PKK (socialist-Kurdish autonomy guerrilla/terrorist group), which intensified its activities in the summer of 2015.

Vast waves of arrest began after the coup attempt, which, unlike the coup itself, have not ended. For the first wave of arrests it was just about possible to believe they were genuine attempts to find coup plotters, but it quickly became apparent that the scope of arrests was much wider. President Erdoğan announced soon after the coup attempt that it was a gift of God and showed how he wanted to use this gift on July 20th, when he proclaimed a state of emergency. The state of emergency has become the means for Erdoğan to purge and punish tens of thousands who have no connection with the coup. The AKP supporters who obsessed about the follow-up coup were right, but the follow-up coup came from their own side. The state of emergency is the real coup, though it is also just a moment in the process of the creation of an AKP-Erdoğanist state, designed to facilitate what appears to be Erdoğan’s final goal (though maybe there will be others later): the creation of an extreme version of the presidential political system in which the head of state is more an elected dictator than the head of a system of checks and balances under law. More soon.

Main postmodern theorists and their main concepts

Postmodernism has been defined as “unbelief about metanarratives.” Metanarratives are great narratives or great stories; comprehensive explanations of the reality around us. Christianity and other religions are examples of metanarratives, but so are scientism and especially the positivism of more recent intellectual history. More specifically, postmodernism questions that there is a truth out there that can be objectively found by the researcher. In other words, postmodernism questions the existence of an objective external reality, as well as the distinction between the subject who studies this reality and object of study (reality itself), and consequently the possibility of a social science free of values, assumptions, or neutrality.

One of the main theorists of postmodernism (or of deconstructionism, to be more exact) was Jacques Derrida (1930-2004). Derrida noted that Western intellectual history has been, since ancient times, a constant search for a Logos. The Logos is a concept of classical philosophy from which we derive the word logic. It concerns an order, or logic, behind the universe, bringing order (cosmos) to what would otherwise be chaos. The concept of Logos was even appropriated by Christianity when the evangelist John stated that “In the beginning was the Logos, and the Logos was with God and the Logos was God,” identifying the Logos with Jesus Christ. In this way, this concept is undoubtedly one of the most influential in the intellectual history of the West.

Derrida, however, noted that this search for identifying a logos (whether it be an abstract spiritual principle, the person of Jesus Christ, or reason itself) implies the formation of dichotomies, or binary oppositions, where one of the elements of the binary opposition is closer to the Logos than the other, but with the two cancelling each other out in the last instance. In this way, Western culture tended to value masculine over feminine, adult over child, and reason over emotion, among other examples. However, as Derrida observes, these preferences are random choices, coupled with the fact that it is not possible to conceive the masculine without the feminine, the adult without the child, and so on. Derrida’s proposal is to identify and deconstruct these binaries, demonstrating how our conceptions are random.

Michel Foucault (1926-1984) developed a philosophical system similar to that of Derrida. At the beginning of his career he was inserted into the post-WWII French intellectual environment, deeply influenced by existentialists. Eventually Foucault sought to differentiate himself from these thinkers, although Nietzsche’s influence can be seen throughout his career. One of the recurring themes in Foucault’s literary production is the link between knowledge and power. Initially identified as a medical historian (and more precisely of psychoanalysis), he sought to demonstrate how behaviors identified as pathologies by psychiatrists were simply what deviated from accepted societal standards. In this way, Foucault tried to demonstrate how the scientific truths elaborated by the doctors were only authoritarian impositions. In a broader sphere he has identified how the knowledge produced by individuals and institutions clothed with power become true and define the structures in which the other individuals must insert themselves. At this point the same hermeneutic of the suspicion that appears in Nietzsche can be observed in Foucault: distrust of the intentions of the one who makes an assertion. The intentions behind an assertion are not always the explicit ones. Foucault’s other contribution was his discussion of the pan-optic, a kind of prison originally envisioned by the English utilitarian philosopher Jeremy Bentham (1748-1832) in which the incarcerated are never sure whether they are being watched or not. The consequence is that the incarcerated need to behave as if they are constantly being watched. Foucault imagined this as a control mechanism applied to everyone in modern society. We are constantly being watched, and charged to suit our standards.

In short, postmodernism questions Metanarratives and our ability to identify absolute truths. Truth becomes relative and any attempt to identify truth becomes an imposition of power over others. In this sense the foundations of modern science, especially in its positivist sense, are questioned. Postmodernism further states that “there is nothing outside the text,” that is, our language has no objective relation to a reality external to itself. Similarly, there is a “death of the author” after the enunciation of a discourse: it is impossible to identify the meaning of a discourse by the intention of the author in writing it, since the text refers only to itself, and is not capable of carrying any sense present in the intention of its author. In this way, discourses should be analyzed not by their relation to a reality external to them or by the intention of the author, but rather in their intertextuality.

The tortuous road to higher education

Below is an excerpt from my book I Used to Be French: an Immature Autobiography. You can buy it on amazon here.

I spent nearly two years aboard a French Navy aircraft carrier between ages 19 and 21. What follows takes place at the end of my period of military service.

Concurrently with the beach-boy fantasies, I developed a more complex and more convoluted life plan, centering on journalism. There was one journalism school in Paris that would accept students without baccalauréat, the sacred university admission exam I had failed twice. The school relied instead on a personal dossier of achievements, a blatant abnormality in the frigid, constipatedly meritocratic French educational system. I thought I might qualify by becoming one of the few French people – aside from some language teachers – who could really write English. Looking back on it, it was an imaginative but reasonable project. I imagined I would go back to California and spend two years in community college, concentrating on writing and literature classes. Older California friends had sent me the catalog of College of Marin, situated near San Quentin prison. I noticed that the college offered many courses in “Penology.” Of course, I thought that those were about using a pen, about writing, in other words. I applied and was accepted on the basis of the social promotion high-school diploma I had obtained during my one year in the US.

As soon as I was discharged from the service, with a one-way train ticket to Paris and fifty of today’s dollars in separation pay, I went back to work at the hotel where I had labored during my teen-age years. I had left such a good impression there that the concierge tried to talk me into becoming his successor. That was not a trivial offer but a sure path to riches. The concierges of high-end hotels are in a position to do wealthy guests many favors, from finding rare theater tickets at the last minute to procuring call-girls in the wee-hours of the morning. Often, both sides of a transaction reward them. Even a prosaic service such as getting shoes resoled overnight generates income. In his early forties, the concierge owned a stable of race horses. His plan was that he would sell me his position and that I would pay him over several years from the graft generated by my talents.

I was absolutely poor so, the offer was tempting. Yet, I declined cordially because, by that time, the thought of studying had become attractive. I saved enough tips in two months to buy a one-way ticket, passage on a student ship to New York, and a little more. On the ship, I met a buxom Christian Scientist blonde who was not a very good Christian but had a lively interest in science, at least in Anatomy. She could not bear to part with me so, she made me detour through Saint-Louis, her hometown. She was sweet and had beaucoup de tempérament, as my mother would have put it, but her father, an Army officer, was soon on to me and I had to keep going. By the way, the same girl had made such a strong impression on me that I hitched-hiked back to Saint Louis in the middle of the winter to be with her. And, no, she wasn’t very beautiful. I cannot tell this story here because writing soft-core is not my purpose right now!

I left Saint Louis by Greyhound bus. I arrived in San Francisco two weeks before classes were to start at the community college. I had no money left at all because the bus had made several stops in Nevada. At twenty-one, after three senior years in high-school (two in France and one in the US), after a few months traveling around Europe and getting into nothing but trouble, after almost two years well warehoused by the French Navy, I was finally ready. Suddenly, I became a first-rate student.

Aggregate measures of well-being, England 1781-1850

I went in the field of economic history after I discovered how much it was to properly measure living standards. The issue that always interested me was how to “capture” the multidimensional nature of living standards. After all, what weight should we give to an extra year of life relative to the quality of that extra year (see all my stuff on Cuba)?

However, I never tried to create “a composite” measure of living standards. I thought that it was necessary, first, to get the measurements right. However, I had been aware of the work of Leandro Prados de la Escosura who has been doing considerable work on this in order to create composite measures (Leandro also influenced me on my Cuba reasoning – see this article).

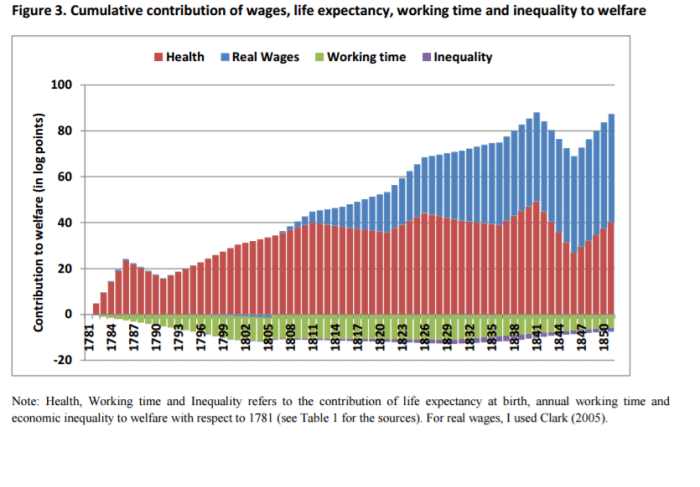

A year ago, I discovered the work of Daniel Gallardo Albarrán from the University of Groningen at the meeting of the Economic History Society (EHS). Daniel’s work is particularly interesting because he is trying to generate a composite measure of well-being at one of the most important moment in history: the start of the British industrial revolution.

Because of its importance and some pieces of contradicting evidence (inequality, stature, amplitude of real wage increases, amplitude of income increases, urban pollution leading to increased mortality risks etc), the period has been begging for some form of composite measure to come along (at least a serious attempt at generating it). Drawing on some pretty straightforward microeconomic theory (the Beckerian in me likes this), Daniel generates this rich graph (see the paper here).

The idea is very neat and I hope it will inspire some economic historians to attempt an expansion upon Daniel’s work. I have already drawn outlines for my own stuff on Canada since I study an era when (from the early 1800s to the mid-1850s) real wages and incomes seem to be going up but stature and mortality are either deteriorating or remaining stable while inequality is clearly increasing.

Star Trek Did More For the Cultural Advancement of Women Than Government Policies

The fondest memories of my childhood center on the time I spent with my father watching Star Trek. At the time, I simply enjoyed science fiction. However, as an adult I have often revisited Star Trek (on multiple occasions) and I realized that I had incorporated subconsciously many elements of the show into my own political reasoning.

Not to give too much away about my age, my passion with Star Trek started largely with the Voyager installments. As a result, I ended up seeing Kate Mulgrew as Captain Janeway. And that’s what she was: the captain. I never saw the relevance that she was a woman. A few years ago, I saw her speak at the Montreal Comic-Con (yes, I am that kind of Trekkie) and she mentioned how crucial she thought her role to be for the advancement of women. By that time, I had already started to consider Star Trek as one of the most libertarian-friendly shows ever to have existed. While its economics were strange, its emphasis on tolerance, non-intervention and equality of rights make it hard to argue that it is not favorable to broadly-defined liberal mindset. However, I had not realized how much so until I heard Mulgrew speak about her vision of the role. After all, I had somehow forgotten that Mulgrew was a woman and how novel her role was.

One person who understands how important was this point is Shannon Mizzi who wrote a piece for Wilson Quarterly which I ended up reading while I was still a PhD student. Her core point was that in Star Trek, women were simply professionals. They were rarely seen doing other things than their work. While she argues that this meant that Star Trek played an underappreciated role in the history of women’s advancement, I am willing to go a step further. That step is to assert that the cause of the cultural advancement of women has been better served by Star Trek than by governments. (Please note that I am only considering cultural advancement)

The pre-1900 economic and social history of women would be sufficient in itself to make this point of mine. After all, women were given a lesser legal status by governments. This is both a necessary and sufficient element to assert that, overall, governments have been noxious to women’s advancement over many centuries. One century of legal emancipation would still leave Star Trek as a net positive force. But that would be a lazy argument on my part and I should simply focus on the present day. In fact, thanks to a wealth of data on wage gaps, gender norms and measures of legal institutions, I can more easily back up the claim.

My friend Rosemarie Fike of Texas Christian University is the first person that comes to mind in that regard. Her own doctoral dissertation, Economic Freedom and the Lives of Women, introduced me to a wide literature on the role of economic freedom in the advancement of women. To be sure, Rosemarie was not the first to try to measure the role of economic freedom (which we should understand as how small and non-interventionist a government is). There had already been some research showing that higher levels of economic freedom were associated with smaller hourly wage gaps between genders and how liberalizing reforms were associated with wage convergence between genders. However, some economists have been arguing that there are other “soft sides” to economic freedom – like in the promotion of cultural equality and norms that promote certain types of attitudes. This is where Rosemarie’s work is most crucial. In a section of her dissertation, she essentially builds up on the work of (my favorite Nobel laureate) Gary Becker regarding preferences and discrimination. Basically, the idea is that free markets will penalize people who willingly discriminate. After all, if an employer refuses to hire redheads for some strange reason, I can compete by hiring the shunned redheads at a lower wage rate and out-compete him. In order to stay in business, the ginger-hating fool has to change his behavior and hire redheads which will push wages up. Its hard to be a racist or misogynist when it costs you a lot of money.

However, if you prevent this mechanism from operating (by intervening in markets), you are making it easier to be bigoted-chauvinistic-male-pigs. As a result, laws that prevent market operations (like the Jim Crow laws did for blacks) enshrine discriminatory practices. Individuals growing up in such environment may accept this as normal and acceptable behavior and strange beliefs about gender equality may cement themselves in the popular imagination. When markets are allowed to operate, beliefs will morph to reflect the actions taken by individuals (see Jennifer Roback’s great story of tramways in the US South as an example of how strong markets can be in changing behavior and see her article on how racism is basically rent-seeking). As a result, Rosemarie’s point is that societies with high levels of economic freedom will be associated with beliefs favorable to gender equality.

But the mirror of that argument is that government policies, even if their spirits have no relation to gender issues, may protect illiberal beliefs. Case in point, women are more responsive to tax rates than men – much more. In short, if you reduce taxes, women will adjust their labor supply more importantly at the extensive and intensive margin than men will. This little, commonly accepted, fact in labor economics is pregnant with implications. Basically, it means that women will work less in high tax environments and will acquire less experience than men will. Since it is also known that differences in the unmeasured effects of experience weigh heavily in explaining the remaining portion of the gender pay gap, this means that high tax rates contribute indirectly to maintaining the small gender pay gap that remains. Now, imagine what would be the beliefs of employers towards women if they did not believe that women are more likely to work fewer hours or drop out of the workforce for some time? Would you honestly believe that they would be the same? When Claudia Goldin argues that changes in labor market structures could help close the gap, can you honestly say that the uneven effect of high tax rates on the labor supply decisions of the different genders are not having an effect in delaying experimentation with new structures? This only one example meant to show that governments may, even when it is not their intent, delay changes that would be favorable to gender equality. There are mountains of other examples going the larger effects of the minimum wage on female employment to the effects of occupational licencing falling heavily on professions where women are predominant.

With such a viewpoint in mind, it is hard to say how much governments helped the cultural advancement of women (on net) over the 20th and 21st centuries . However, Star Trek clearly had a positive net effect on that cultural advancement. That is why I am willing to say it here: Star Trek did more for the cultural advancement of women than governments did.

Why do we teach girls that it’s cute to be scared?

I just came across this fantastic op-ed while listening to the author being interviewed.

The author points out that our culture teaches girls to be afraid. Girls are warned to be careful at the playground while boys are expected… to be boys. Over time we’re left with a huge plurality of our population hobbled.

It’s clear that this is a costly feature of our culture. So why do we teach girls to be scared? Is there an alternative? This cultural meme may have made sense long ago, but society wouldn’t collapse if it were to disappear.

Culture is a way of passing knowledge from generation to generation. It’s not as precise as science (another way of passing on knowledge), but it’s indispensable. Over time a cultural repertoire changes and develops in response to the conditions of the people in that group. Routines, including attitudes, that help the group succeed and that are incentive-compatible with those people will persist. When groups are competing for resources, these routines may turn out to be very important.

It’s plausible that in early societies tribes had to worry about neighboring tribes stealing their women. For the tribe to persist, there needs to be enough people, and there needs to be fertile women and men. The narrower window for women’s productivity mean that men are more replaceable in such a setting. So tribes that are protective of women (and particularly young women and girls) would have an cultural-evolutionary advantage. Maybe Brandon can tell us something about the archaeological record to shed some light on this particular hypothesis.

But culture will be slower to get rid of wasteful routines, once they catch on. For this story to work, people can’t be on the razor’s edge of survival; they have to be wealthy enough that they can afford to waste small amounts of resources on the off-chance that it actually helped. Without the ability to run randomized control trials (with many permutations of the variables at hand) we can never be truly sure which routines are productive and which aren’t. The best we can do is to try bundles of them all together and try to figure out which ones are especially good or bad.

So culture, an inherently persistent thing, will pick up all sorts of good and bad habits, but it will gradually plod on, adapting to an ever-changing, ever evolving ecosystem of competing and cooperating cultures.

So should we still teach our girls to be scared? I’d argue no.* Economics tells us that being awesome is great, but in a free society** it’s also great when other people are awesome. Those awesome people cure diseases and make art. They give you life and make life worth living.

Bringing women and minorities into the workplace has been a boon for productivity and therefore wealth (not without problems, but that’s how it goes). Empowering women in particular, will be a boon for the frontiers of economic, scientific, technical, and cultural evolution to the extent women are able to share new view points and different ways of thinking.

And therein lies the rub… treating girls like boys empowers them, but also changes them. So how do we navigate this tension? The only tool the universe has given us to explore a range of possibilities we cannot comprehend in its entirety: trial and error.

We can’t run controlled experiments, so we need to run uncontrolled experiments. And we need to try many things quickly. How quickly depends on a lot of things and few trials will be done “right.” But with a broader context of freedom and a culture of inquiry, our knowledge can grow while our culture is enriched. I think it’s worth making the bet that brave women will make that reality better.

* But also, besides what I think, if I told parents how to act… if I made all of them follow my sensible advice, I’d be denying diversity of thought to future generations. That diversity is an essential ingredient, both because it allows greater differences in comparative advantage, but also because it allows more novel combinations of ideas for greater potential innovation in the future.

** And here’s the real big question: “What does it mean for a society to be free?” In the case of culture it’s pretty easy to say we want free speech, but it runs up against boundaries when you start exploring the issue. And with billions of people and hundreds (hopefully thousands) of years we’re looking at a thousand-monkey’s scenario on steroids… and that pill from Flowers for Algernon.

There’s copyright which makes it harder to stand on the shoulders of giants, but might be justified if it helps make free speech an economically sustainable reality. There’s the issue of yelling “Fire!” in a crowded theater, and the question of how far that restriction can be stretched before political dissent is being restricted. We might not know where the line should be drawn, but given enough time we know that someone will cross it.

And the issue goes into due process and business regulation, and any area of governance at all. We can’t be free to harm others, but some harms are weird and counter-intuitive. If businesses can’t harm one another through competition then our economy would have a hard time growing at all. Efficiency would grow only slowly tying up resources and preventing innovation. Just as there’s an inherent tension in the idea of freedom between permissiveness and protection, there’s a similar tension in the interdependence of cooperation and competition for any but the very smallest groups.

The existentialist origins of postmodernism

In part, postmodernism has its origin in the existentialism of the 19th and 20th centuries. The Danish theologian and philosopher Søren Kierkegaard (1813-1855) is generally regarded as the first existentialist. Kierkegaard had his life profoundly marked by the breaking of an engagement and by his discomfort with the formalities of the (Lutheran) Church of Denmark. In his understanding (as well as of others of the time, within a movement known as Pietism, influential mainly in Germany, but with strong precedence over the English Methodism of John Wesley) Lutheran theology had become overly intellectual, marked by a “Protestant scholasticism.”

Scholasticism was before this period a branch of Catholic theology, whose main representative was Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274). Thomas Aquinas argued against the theory of the double truth, defended by Muslim theologians of his time. According to this theory, something could be true in religion and not be true in the empirical sciences. Thomas Aquinas defended a classic concept of truth, used centuries earlier by Augustine of Hippo (354-430), to affirm that the truth could not be so divided. Martin Luther (1483-1546) made many criticisms of Thomas Aquinas, but ironically the methodological precision of the medieval theologian became quite influential in Lutheran theology of the 17th and 18th centuries. In Germany and the Nordic countries (Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway and Sweden) Lutheranism became the state religion after the Protestant Reformation of the 16th century, and being the pastor of churches in major cities became a respected and coveted public office.

It is against this intellectualism and this facility of being Christian that Kierkegaard revolts. In 19th century Denmark, all were born within the Lutheran Church, and being a Christian was the socially accepted position. Kierkegaard complained that in centuries past being a Christian was not easy, and could even involve life-threatening events. In the face of this he argued for a Christianity that involved an individual decision against all evidence. In one of his most famous texts he makes an exposition of the story in which the patriarch Abraham is asked by God to kill Isaac, his only son. Kierkegaard imagines a scenario in which Abraham does not understand the reasons of God, but ends up obeying blindly. In Kierkegaard’s words, Abraham gives “a leap of faith.”

This concept of blind faith, going against all the evidence, is central to Kierkegaard’s thinking, and became very influential in twentieth-century Christianity and even in other Western-established religions. Beyond the strictly religious aspect, Kierkegaard marked Western thought with the notion that some things might be true in some areas of knowledge but not in others. Moreover, its influence can be seen in the notion that the individual must make decisions about how he intends to exist, regardless of the rules of society or of all empirical evidence.

Another important existentialist philosopher of the 19th century was the German Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900). Like Kierkegaard, Nietzsche was also raised within Lutheranism but, unlike Kierkegaard, he became an atheist in his adult life. Like Kierkegaard, Nietzsche also became a critic of the social conventions of his time, especially the religious conventions. Nietzsche is particularly famous for the phrase “God is dead.” This phrase appears in one of his most famous texts, in which the Christian God attends a meeting with the other gods and affirms that he is the only god. In the face of this statement the other gods die of laughing. The Christian God effectively becomes the only god. But later, the Christian God dies of pity for seeing his followers on the earth becoming people without courage.

Nietzsche was particularly critical of how Christianity in his day valued features which he considered weak, calling them virtues, and condemned features he considered strong, calling them vices. Not just Christianity. Nietzsche also criticized the classical philosophy of Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle, placing himself alongside the sophists. The German philosopher affirmed that Socrates valued behaviors like kindness, humility, and generosity simply because he was ugly. More specifically, Nietzsche questioned why classical philosophers defended Apollo, considered the god of wisdom, and criticized Dionysius, considered the god of debauchery. In Greco-Roman mythology Dionysius (or Bacchus, as he was known by the Romans) was the god of festivals, wine, and insania, symbolizing everything that is chaotic, dangerous, and unexpected. Thus, Nietzsche questioned the apparent arbitrariness of the defense of Apollo’s rationality and order against the irrationality and unpredictability of Dionysius.

Nietzsche’s philosophy values courage and voluntarism, the urge to go against “herd behavior” and become a “superman,” that is, a person who goes against the dictates of society to create his own rules . Although he went in a different religious direction from Kierkegaard, Nietzsche agreed with the Danish theologian on the necessity of the individual to go against the conventions and the reason to dictate the rules of his own existence.

In the second half of the 20th century existentialism became an influential philosophical current, represented by people like Jean-Paul Sartre (1905-1980) and Albert Camus (1913-1960). Like their predecessors of the 19th century, these existentialists criticized the apparent absurdity of life and valued decision-making by the individual against rational and social dictates.

Famine and Finance: Credit and the Great Famine of Ireland

I have recently finished reading Famine and Finance by Tyler Beck Goodspeed. While short, it should have a prominent place on the shelves of economic historians interested (obviously) in Irish history and (less obviously) in Malthusian theory.

I have recently finished reading Famine and Finance by Tyler Beck Goodspeed. While short, it should have a prominent place on the shelves of economic historians interested (obviously) in Irish history and (less obviously) in Malthusian theory.

Famine and Finance is a study of the response of Irish farmers to the potato blight. As it is known to many, many individuals simply left Ireland. However, where micro-credit was available, Goodspeed finds that farmers adapted by shifting to different types of activities – notably livestock. These areas experienced a smaller decline in population. Basically, where the institution of micro-credit was present, the demographic shock was much less severe. If only for this nuance, the book makes a sizeable contribution to the historiography of Ireland. The methods used are also elegantly simple and provide an interesting road map for anyone interested in studying the responses of local population to environmental shocks.

However, the deeper point comes from it tells us about institutions. In Goodspeed’s story, the amplitude of the collapse of the Irish population in the 19th century depends on the presence of the institution of micro-credit. Basically, the institution determined the amplitude of the shock. Since Ireland’s potato blight is often presented as the textbook case of Malthusian pressures, Goodspeed’s results are particularly interesting. In his chatper titled”Was Malthus Right?”, he shows that when controls for the institution of micro-credit is present, the typical Malthusian variables fail to explain population changes. In other words (i.e. my words) , Malthusian pressures (the change in population) are in fact institutional failures.

This is a point I have often made elsewhere (see here, here and here and a blog post here). And because Goodspeed backs this point of mine, he has earned himself a place on my shelf of “go-to” books.

The Latin American tropism

Below is an excerpt from my book I Used to Be French: an Immature Autobiography. You can buy it on amazon here.

The Paris in which I grew up (outside of the long summer vacations), was a gray, dank and dark place. It was an easy locale from which to fantasize about the sun-drenched tropics. Palm-trees were our favorite trees because we never saw any except at the movies. Of all the tropics, the Latin American tropics took pride of place. Perhaps that was because France had negligible colonial entanglement there and therefore, no colonial retirees to mug our fantasy with their recollections of reality. Or perhaps, it was because, well after the emergence of rock-and-roll in France, close dancing was still taking place to the sound of Latin music: Rumba, Samba, Tango. One sensuous experience easily becomes grafted onto another; the clinging softness of girls’ flesh became associated in our minds with that particular kind of music and thence, with a whole unknown continent. This cocktail of sensations biased me until now in favor of that continent.

At one of the stops where several foreign student buses met, I became smitten with a Bolivian girl and she with me. We were to each other the most exotic thing ever touched. She had luscious brown skin, thick, black, lustrous Indian hair, swinging hips, and a lovely round chest. Our buses met again several times and the passion was renewed each time. Although those encounters involved little more than many sloppy deep kisses and some furious mutual groping, indirectly, they were to shape an important part of my mental life, a favorable disposition toward the otherness of others, “xenophilia,” if you will.

The Heights of French-Canadian Convicts, 1780 to 1830

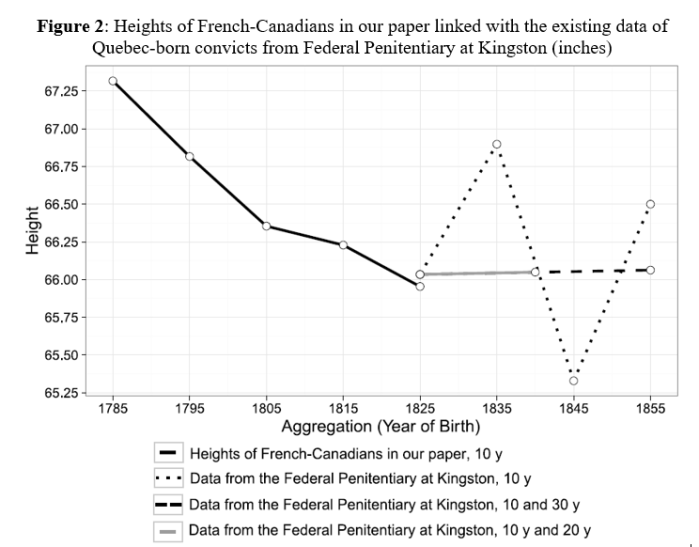

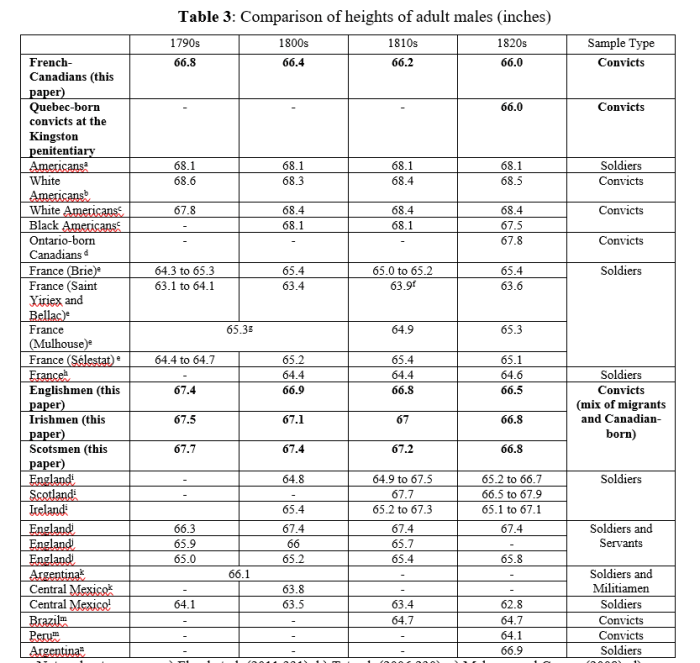

A few days ago, it was confirmed that my article with Vadim Kufenko and Alex Arsenault Morin on the heights of French-Canadians between 1780 and 1830 was accepted for publication in Economics and Human Biology. In that paper, we try to introduce French-Canadians before 1850 to the anthropometric history literature by using the records of the prison of Quebec City. Stature is an important measure of living standards. As it is heavily related to other aspects of health outcomes, it is a strong measure of biological living standards. More importantly, there are moments in history when material living standards and biological living standards move in opposite directions (in the long-run, this is not the case).

We find three key results. The first is that the French-Canadians grew shorter throughout the era when living standards did not increase importantly (and were very volatile). This puts them at odds from other places in North America where increases in stature were experienced up until the 1820s. Furthermore, stature stops falling around 1820 when economic growth picked up. This places the French-Canadians in a unique category in North America since it seems unlikely that they experienced a strong version of the antebellum puzzle (decline in stature with increases in material living standards which is what the US experienced). The second key result is that the French-Canadians are the shortest in North America, shorter even than Black Americans in slavery. However, they are considerably taller than most (save Argentinians) Latin Americans. More importantly, they are considerably taller than their counterparts in France. The third key result is related to the second key result. Today, French-Canadians are noticeably shorter than other Canadians. However, the gap was more important in the late 19th century and early 20th century. Pegged as a “striking exception” within Canada, we do not know when it actually started. Thanks to our work, we know that this was true as far back at the early 19th century.

The working paper (dramatically different than the accepted version) is here and I am posting key results in tables and figures below. Moreover, I will be talking about anthropometric history and economic history with Garrett Petersen of Economics Detective Radio this Tuesday (I do not know when the podcast will be made available, but you should subscribe to that show anyways).

Immigration, Cultural Change, and Diversity as a Cultural Discovery Process

I have spent a couple of posts addressing various spurious economic and fiscal arguments against looser immigration restrictions. But, as Brandon pointed out recently, these aren’t really the most powerful arguments for immigration restrictions. Most of Donald Trump’s anti-immigrant rhetoric revolves around strictly alleged cultural costs of immigration. I agree that for all the economic rhetoric used in these debates, it is fear of the culturally unfamiliar that is driving the opposition. However, I still think the tools of economics that are used to address whether immigration negatively impacts wages, welfare, and unemployment can be used to address the question of whether immigrants impact our culture negatively.

One of the greatest fears that conservatives tend to have of immigration is the resulting cultural diversity will cause harmful change in society. The argument goes that the immigrant will bring “their” customs from other countries that might do damage to “our” supposedly superior customs and practices, and the result will be a damage to “our” long-held traditions and institutions that make “our” society “great.” These fears include, for example, lower income immigrants causing higher divorce rates spurring disintegration of the family, possible violence coming from cultural differences, or immigrants voting in ways that are not conducive to what conservatives tend to call “the founding principles of the republic.” Thanks to this insight, it is argued, we should restrict immigration or at least force prospective immigrants to hop through bureaucracy so they may have training on “our” republican principles before becoming citizens.

There are a number of ways one may address this argument. First, one could point out that immigrants face robust incentives to assimilate into American culture without needing to be forced to by restrictive immigration policies. One of the main reasons why immigrants come to the United States is for better economic opportunity. However, when immigrants are extremely socially distant from much of the native population, there a tendency for natives to trust them less in market exchange. As a result, it is in the best interest of the immigrant to adopt some of the customs of his/her new home in order to reduce the social distance to maximize the number of trades. (A more detailed version of this type of argument, in application to social and cultural differences in anarchy, can be found in Pete Leeson’s paper Social Distance and Self-Enforcing Exchange).

The main moral of the story is that peaceable assimilation and social cohesion comes about through non-governmental mechanisms far more easily than is commonly assumed. In other words, “our” cultural values are likely not in as much danger as conservatives would have you think.

Another powerful way of addressing this claim is to ask why should we assume that “our” ways of doing things is any better than the immigrant’s home country’s practices? Why is it that we should be so resistant to the possibility that culture might change thanks to immigration and cultural diversity?

It is tempting for conservatives to respond that the immigrant is coming here and leaving his/her home, thus obviously there is something “better” about “our” cultural practices. However, to do so is to somewhat oversimplify why people immigrate. Though it might be true that, on net, they anticipate life in their new home to be better and that might largely be because “our” institutions and cultural practices are on net better, it is a composition fallacy to claim that it follows from this that all our institutions are better. There still might be some cultural practices that immigrants would want to keep thanks to his/her subjective value preferences from his or her country, and those practices very well might be a more beneficial. This is not to say our cultural practices are inherently worse, or that they are in every instance equal, just that we have no way of evaluating the relative value of cultural practices ex ante.

The lesson here is that we should apply FA Hayek’s insights from the knowledge problem to the evolution of cultural practices in much the way conservatives are willing to apply it to immigration. There is no reason to assume that “our” cultural practices are better than foreign ones; they may or may not be, but it is a pretense of knowledge to attempt to use state coercion to centrally plan culture just as it is a pretense of knowledge to attempt to centrally plan economic production.

Instead of viewing immigration as a necessary drain on culture, it may be viewed as a potential means of improving culture through the free exchange of cultural values and practices. In the market, individuals are permitted to experiment with new inventions and methods of production because this innovation and risk can lead to better ways of doing things. Therefore, entrepreneurship is commonly called a “discovery process;” it is how humanity may ‘discover’ newer, more efficient economic production techniques and products.

Why is cosmopolitan diversity not to be thought of as such a discovery process in the realm of culture? Just as competition between firms without barriers to entry brings economic innovation, competition between cultural practices without the barrier to entry of immigration laws may be a means of bettering culture. When thought of in that light, the fact that our cultural traditions may change is not so daunting. Just as there is “creative destruction” of firms in the marketplace, there is creative destruction of cultural practices.

Conservative critics of immigration may object that such cultural diversity may cause society to evolve in negative ways, or else they may object and claim that I am not valuing traditions highly enough. For the first claim, there is an epistemic problem here on how we may know which cultural practices are “better.” We may have our opinions, based on micro-level experience, on which cultural practices are better, and we have every right to promote those in non-governmental ways and continue to practice them in our lives. Tolerance for such diversity is what allows the cultural discovery process to happen in the first place. However, there is no reason to assume that our sentiments towards our tradition constitute objective knowledge of cultural practices on the macro-level; on the contrary, the key insight of Hayek is it is a fatal conceit to assume such knowledge.

As Hayek said in his famous essay Why I’m Not a Conservative:

As has often been acknowledged by conservative writers, one of the fundamental traits of the conservative attitude is a fear of change, a timid distrust of the new as such, while the liberal position is based on courage and confidence, on a preparedness to let change run its course even if we cannot predict where it will lead. There would not be much to object to if the conservatives merely disliked too rapid change in institutions and public policy; here the case for caution and slow process is indeed strong. But the conservatives are inclined to use the powers of government to prevent change or to limit its rate to whatever appeals to the more timid mind. In looking forward, they lack the faith in the spontaneous forces of adjustment which makes the liberal accept changes without apprehension, even though he does not know how the necessary adaptations will be brought about. It is, indeed, part of the liberal attitude to assume that, especially in the economic field, the self-regulating forces of the market will somehow bring about the required adjustments to new conditions, although no one can foretell how they will do this in a particular instance.

As for the latter objection that I’m not valuing tradition, what is at the core of disagreement is not the value of traditions. Traditions are highly valuable: they are the cultural culmination of all the tacit knowledge of the extended order of society and have withstood the test of time. The disagreement here is what principles we ought to employ when evaluating how a tradition should evolve. The principle I’m expressing is that when a tradition must be forced on society through state coercion and planning, perhaps it is not worth keeping.

Far from destroying culture, the free mobility of individuals through immigration enables spontaneous order to work in ways which improve culture. Immigration, tolerance, and cultural diversity are vital to a free society because it allows the evolution and discovery of better cultural practices. Individual freedom and communal values are not in opposition to each other, instead the only way to improve communal values is through the free mobility of individuals and voluntary exchange.

On power-display bias and the historians

This is an excerpt from my upcoming book at Palgrave McMillan which discusses Canadian economic history. This excerpt relates to a point that I have made numerous times on this blog regarding the bias for power held by historians and how it often leads them to inaccurate conclusions (here and here):

When the great historian Lord Acton warned that, “absolute power corrupts absolutely,” he was not only referring to imbuing certain fallible humans with excessive powers, but also as a caution to historians for their assessment of politicians. Too often, politicians become known for “greatness” because of their actions, regardless of how much they impoverished society or put in place measures that would ultimately erode their citizens’ quality of life. By the same token, some eminent figures remain unknown, relegated to a footnote in the history books, even though they have contributed in a more significant way to economic enrichment, cultural development, and social cohesion. Grand gestures and large-scale social projects inspired by good intentions do not always yield great results – or desirable ones.

If we truly want to assess the Quiet Revolution and the “Great Darkness” with any clarity, we must consider politicians’ actions in a more realistic scope, and sift through the quantitative and qualitative data that show how people thought and acted in the everyday. Through the use of rigorous tools, statistical methods and economic theories, we ought to consider how things might reasonably have developed otherwise without the Quiet Revolution. This is what I have tried to do in this book. (…)

The discourse on Quebec modernity that emerged along with the Quiet Revolution coincided with the emergence of a strong interventionist State. When we compare Quebec to other Western countries, however, our analysis reveals that the State did not play a major role in modernization here. After all, it was in a period when Quebec’s State apparatus was less active compared to the rest of Canada that it was able to progress in leaps and bounds. Of course, the State must have had some effect in certain areas, but the Quiet Revolution was not responsible for the bulk of positive outcomes that came to term during this period. Analyzing trends, causes, explanations and secondary forces at play in Quebec society’s metamorphosis definitely requires a degree of patience and effort. It would be much less onerous to take the easier path of only looking at the State’s activities as worthy of attention in this regard. If we fail to make these efforts, we risk succumbing to the “Nirvana Fallacy.” In order words, we tend to put the State on a pedestal: it becomes a kind of disembodied entity in a virtual reality where it plays the VIP or starring role. Comparing reality with a utopia necessary leads us to conclude that utopia is better, but this approach is utterly fruitless.

Illegal Immigration: Pres. Trump’s New Measures

I can’t wait for the raging assaults by the pseudo-cultural elite and by the media against Pres. Trump to stop to begin criticizing some of his decisions, as I would with any other president.

I have heard and read reports that the president intends to launch a policy of accelerated repatriation of illegal aliens. It will single out criminals for priority deportation (as was the case under Mr Obama). At this point, almost everybody agrees about getting rid of illegal aliens who are real criminals, especially the violent ones. Again, the new policy sounds a lot like Mr Obama’s, with a few details different. The details often matter when it comes to human lives, also when it comes to traditions of government. Here are two such details.

First, I have heard that even traffic tickets qualify an illegal alien for quick deportation. Make a wrong u-turn and your life gets broken up.

Second, I have heard and read that even being merely charged with a crime places you at the head of the line for deportation. Someone who looks like you steals a car. You get charged by mistake. You are gone.

The first detail seems awfully rough to me. I would feel better if the word “recidivist” were included. A person who breaks driving rules repeatedly is a trouble-maker we can do without. A guy who is too distracted to interpret the U-turn sign (could be me – once) is not exactly a criminal in the real sense of the word.

It’s true that such extreme severity would improve the driving of all illegal aliens. The claim is probably also correct however that it would interfere with aliens’ (legal and not) willingness to cooperate with the local police. Aside from this, I would bet it would involve significant law enforcement costs just to process traffic tickets through to the Immigration Service. I am a conservative, I am against big government, even against big government at the local level. I don’t want tax money, federal, state, or local, to be wasted processing a U-turn violator. It seems irrational to me.

The second, detail concerns the treatment of people only charged with a crime. It’s simple. I just don’t want any of them to be included in the priority list. Having any branch of government treating the accused as guilty simply goes too strongly against everything I believe. It’s un-American.

Yes, I have not forgotten that the subjects have no right to be in the country in the first place. I don’t care. It’s not about illegal aliens’ rights. Immigrants, legal or not, have no rights as a category as far as I am concerned. They only possess the ordinary human rights of anyone under American jurisdiction.

It’s about a slippery slope for all. If we begin officially thinning out the traditional wall between “charged” and “guilty,” where are we going to stop?

I understand that a lawyer would argue that the person is technically not being deported for the imaginary crime of being charged but because he has no right to be in the country, period. Do you know the one about the lawyer….

Brazil six months after Dilma Rousseff

Six months after President Dilma Rousseff’s impeachment, Brazil remains plunged into one of the biggest crises in its history. Economically the outlook is worrisome, with little chance that the country will grow again anytime soon. Politically the government of President Michel Temer has little credibility. Although brought to power by a process whose legitimacy cannot be questioned (even if groups linked to the former president still insist on the narrative of the coup – although without the same energy as before), Temer has no expressive popular support and is attached to oligarchic interests difficult to circumvent. In other areas, the crisis is also present: urban violence is increasing, unemployment, especially among the young, remains high, and education is among the worst in the world, among other examples. It is surprising that Brazil, considering its GDP, is one of the largest economies on the planet.

As I predicted in a previous article, Dilma Rousseff’s departure from power, however just and necessary, would not be the solution to all Brazil’s problems. Rousseff, although president of the country, was far from having a leading role in the Brazilian reality. As local press often put it, she was just a pole put in place by former President Luis Inacio Lula da Silva hoping to one day return to power (which he never completely left). Today, however, Lula is the target of several corruption investigations and is expected to go to jail before he can contest new elections. Meanwhile, the government of Michel Temer offers little news compared to the previous.

Michel Temer is a lifelong member of PMDB. PMDB was formed during the Military Government that lasted from the early 1960s to the early 1980s. It was the consented opposition to the military, and eventually added a wide variety of political leadership. Leaving the military leadership period, some tried to keep the PMDB united as a great democratic front, but this was neither doable nor desirable. Keeping the PMDB together was not feasible because what united its main leaders was only opposition to the military government. In addition, the party added an irreconcilable variety of political ideas and projects, and it was not desirable to keep them together because it would be important for Brazilian political leaders to show their true colors at a moment when internationally the decline of socialism was being discussed. After a stampede of many of its most active leadership to other parties (mainly to the PSDB), the PMDB became a pragmatic, often oligarchic, legend and without clear ideological orientation, very similar to the Mexican PRI.

Being a party of national expression, the PMDB had oscillating relations with all Brazilian governments since the 1980s, but with one certainty: the PMDB is a party that does not play to lose. Eventually a part of the party leadership understood that the arrival of the PT to the presidency of the country was inevitable and proposed an alliance. This explains the presence of Temer as Rousseff’s vice president. But it would be wrong to say that the PMDB simply joined the winning team: the PT was immeasurably benefited by the alliance, and probably would not have reached or remained in power without the new ally. The alliance with the PT also showed that, despite the ideological discourse, the PT had little novelty to offer to Brazilian politics.

Although he has waved with reforms in favor of economic freedom, Temer has done little that can considered new so far. The freezing of government spending, well received by many right-wing groups, does not really touch the foundations of Brazilian statism: the government remains almost omnipresent, only without the same money to play its part. The proposed pension reform, similarly, does not alter the fundamentals of the state’s relationship with society. Finally, Temer put the economic policy in the hands of Henrique Meirelles, who had already been President of the Central Bank of Lula. Meirelles is one of the main responsible for the crisis that the country faces today, and its revenue to get around the problems remains the same: stimulus spending. In other words, do more of what brought us to the current situation in the first place.

A positive aspect of the current Brazilian crisis is the emergence or strengthening of right-wing political groups. Although the Brazilian right still is quite authoritarian, there are inclinations in favor of the free market being strengthened. Of course, strengthening a pro-market right annoys the left, and this is perhaps the best sign that this is a political trend gaining real space. While it is still difficult to see a light at the end of the tunnel, the 2018 presidential election may be the most relevant to the country since 1989.