Draft material for a joint conference paper/Work in Progress on a long term project

This paper comes out of a long term project to work on ideas of liberty in relation to republicanism in political thought, along with issues of law and sovereignty. The paper in question here comes out of collaborative work on questions of law, judgement, and republicanism in relation to Turkey’s history and its current politics. Though this comes from collaborative work, I take sole responsibility for this iteration of draft material towards a joint conference paper, drafted with the needs of a blog with a broad audience in mind.

The starting point is in Immanuel Kant with regard to his view of law and judgement. His jurisprudence, mostly to be found in the first part of the Metaphysics of Morals on ‘The Doctrine of Right’, is that of law based on morality, so is an alternative to legal positivism. The argument here is not to take his explicit jurisprudence as the foundation of legal philosophy. There is another way of looking at Kant’s jurisprudence which will be discussed soon.

What is particularly valuable at this point is that Kant suggests an alternative to legal positivism and the Utilitarian ethics with which is has affinities, particularly in Jeremy Bentham. Legal positivism refers to a position in which laws are commands understood only as commands, with regard to some broader principles of justice. It is historically rooted in the idea of the political sovereign as the author of laws. Historically such a way of thinking about law was embedded in what is known to us as natural law, that is, ideas of universal rules of justice. This began with a very sacralised view of law as coming from the cosmos and divine, in which the sovereign is part of the divinely ordained laws. Over time this conception develops more into the idea of law as an autonomous institution resting on sovereign will. Positivism develops from such an idea of legal sovereignty, leaving no impediment to the sovereign will.

Kant’s understanding of morality leaves law rooted in ideas of rationality, universality, human community, autonomy, and individual ends which are central to Kant’s moral philosophy. The critique of legal positivism is necessary to understanding law in relation to politics and citizenship in ways which don’t leave a sovereign will with unlimited power over law. Kant’s view of judgement suggests a way of taking Kant’s morality and jurisprudence out of the idealist abstraction he tends towards. His philosophy of judgement can be found in the Critique of Judgement Power, divided into parts on aesthetic judgments of beauty and teleological judgments of nature.

The important aspect here is the aesthetic judgement, given political significance through the interpretation of Hannah Arendt. From Arendt we can take an understanding of Kant’s attempts at a moral basis for law, something that takes political judgement as an autonomous, though related, area. On this basis it can be said that the judgement necessary for there to be legal process, bringing particular cases under a universal rule, according to a non-deterministic subjective activity, on the model of Kant’s aesthetic judgement is at the root of politics.

Politics is a process of public judgement about particular cases in relation to the moral principles at the basis of politics. The making of laws is at the centre of the political process and the application of law in court should also have a public aspect. We can see a model of a kind in antiquity with regard to the minor citizen assembly, selected by lottery, serving as a jury in the law courts of ancient Athens. It is Roman law that tends to impose a state oriented view of law, in which the will of the sovereign is applied in a very absolutist way, so that in the end the Emperor is highest law maker and highest judge of the laws.

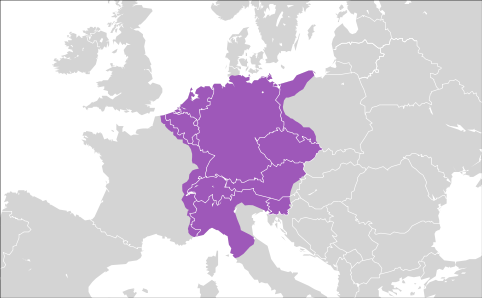

As Michel Foucault argues, and Montesquieu before him, the German tribes which took over Roman lands had more communal and less rigidly defined forms of court judgement, and were more concerned with negotiating social peace than applying laws rigidly to cases. Foucault showed how law always has some political significance with regard to the ways in which sovereignty works and power is felt. That is the law and the work of the courts is a demonstration of sovereignty, while punishment is concerned with the ways that sovereignty is embedded in power, and how that power is exercised on the body to form a kind of model subjugation to sovereignty. The Foucauldian perspective should not be one in which everything to do with the laws, the courts, and methods of punishment is an expression of politics narrowly understood.

The point is to understand sovereignty as whole, including the inseparability of institutions of justice from the political state. The accountability of the state and the accountability of justice must be taken together. Both should work in the context of public accessibility and public discussion. The ways in which laws, courts, and judges can be accountable to ideas of autonomy must be declared and debate. Courts should be understood as ways of addressing social harms and finding reconciliation rather than as the imposition of state-centric declarations of law.