- Will UCLA ever escape John Wooden’s shadow? ESPN

- The politics of the classics in Japan John D’Amico, JHIBlog

- When Pakistan had jazz and cabarets in abundance Ali Bhutto, Guardian

- Lego vs. Lepin Rob Fisher, Samizdata

imperialism

Nightcap

- The last (effortless) rulers of the world Branko Milanovic, globalinequality

- How TikTok is rewriting the world John Herrman, New York Times

- Empires of the weak: European imperialism reconsidered Peter Gordon, Asian Review of Books

- The place that launched a thousand ships Sean McMeekin, Literary Review

Nightcap

- Ottoman nostalgia (back to the Balkans) Alev Scott, History Today

- Did post-Marxist theories destroy Communist regimes? Branko Milanovic, globalinequality

- Islam in Eastern Europe (a silver thread) Jacob Mikanowski, Los Angeles Review of Books

- Against Imperial Nostalgia: Or why Empires are Kaka Barry Stocker, NOL

Nightcap

- The St. Valentine’s Day massacre Evan Bleier, RealClearLife

- The Sons of Mars and the ancient Mediterranean Erich Anderson, History Today

- The two trilemmas today Branko Milanovic, globalinequality

- How the United States reinvented empire Patrick Iber, New Republic

Nightcap

- Pontius Pilate: the first Christian? Branko Milanovic, globalinequality

- Politics and forgiveness – a leftist proposal John Holbo, Crooked Timber

- Bumps on the road to pot legalization Irfan Khawaja, Policy of Truth

- America’s bewildering imperialism Damon Linker, the Week

Nightcap

- Olive Oatman Ann Turner, 3 Quarks Daily

- Don’t let the rise of Europe steal world history Peter Frankopan, Aeon

- Africa’s forgotten empires David Olusoga, New Statesman

- Colonialism: Myths and Realities Brandon Christensen, NOL

RCH: Annexation of the Hawaiian islands

That’s the topic of my latest over at RealClearHistory. An excerpt:

That is to say, there are theoretical lessons we can draw from the American annexation of Hawaii and apply them to today’s world. The old Anglo-Dutch playbook turned out to serve American imperial interests well, especially when contrasted with the disastrous Spanish-American War of 1898, when the United States seized the Philippines, Cuba, Guam, and Puerto Rico from Spain in an unwarranted act of aggression. Hawaii, now an American state, has one of the highest standards of living in the world (including for its indigenous and Japanese citizens), while the territories seized by the U.S. from Spain continue to wallow in relative poverty and autocratic governance.

Please, read the rest.

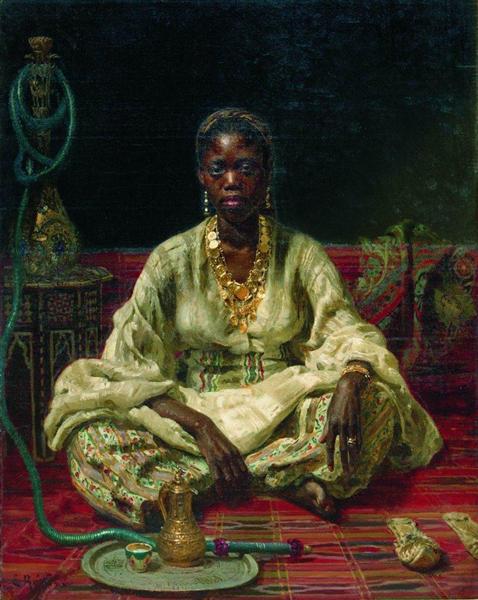

Afternoon Tea: Negress (1876)

This is from Russian painter Ilya Repin:

RCH: Crazy Horse’s last battle

I’m back at it over at RealClearHistory. An excerpt:

When the Indian wars were underway, the battles were characterized as two very different peoples fighting against each other. Today, this view is still espoused, but the logic underneath has changed. Today, the American Indian fighting the American soldier has come to be viewed as more of a civil war than a clash of civilizations. The Native Americans are deeply intertwined in our culture, our history. As historical research gets better, thanks in part to the fact that our society continues to get wealthier and wealthier, the indigenous actors who helped shape American history receive more attention, empirically and theoretically.

Crazy Horse’s last battle in Montana against the U.S. Army highlights this civil war better than most. The Sioux and Cheyenne were not being pursued to be eliminated, but to be domesticated and transformed, by a benevolent government with the best of intentions, into American citizens.

Please, read the rest.

RCH: the Christmas Battles in Latvia

That’s the subject of this weekend’s column over at RealClearHistory. An excerpt:

9. The battles didn’t actually take place on Christmas Day. They actually occurred in early January. However, under the old czarist Julian calendar, the battles occurred over the Christmas season, from Dec. 23-29. The Germans were caught by surprise because even though it was January in the West, it was Christmas season in Russia and the Germans believed the Russians would be celebrating their Christmas rather launching a major counter-offensive.

And

3. The Siberians were eventually slaughtered. The Siberians who refused to fight were not necessarily betraying their Latvian brothers-in-imperium. They knew they were cannon fodder. And, indeed, when the Siberians finally went to reinforce the Russian gains made, they were greeted with a massive German counter-offensive. The Siberians (and others) were left for dead. They received no food, no weapons, and no good tidings of comfort and joy.

Please, read the rest (and tell your friends about it). It’s my last post at RCH for the year, so there’s lots of links to other World War I-themed articles I wrote throughout 2018.

Why Cultural Marxism is a big deal for Brazil, and also for you

I already heard the criticism that cultural Marxism is not a real thing. It’s just a scary word, like neoliberalism, that doesn’t mean anything really. Well, for those who think that way, please pay a visit to Brazil.

When I talk about cultural Marxism, here is what I have in mind: I’m not a specialist in Marx or Marxism by any means, but what I understand is that Marx gravitated towards economic theory in his life. He began his intellectual journey more like a general philosopher but ended more like an economist. A very bad economist. Marx’s economic theory in The Capital is based on the premise of the labor theory of value: things cost what they cost depending on how much work it takes to produce them. Of course, this theory does not represent reality. You take the labor theory of value, Marx’s economic theory crumbles down. That is what Mises explained on paper at the beginning of the 20th century and reality proved throughout it everywhere and every time people tried to put Marxism into practice.

Although Marx’s economic theory didn’t work, Marx’s admirers didn’t give up. In Russia Lenin tried to explain that capitalism survived because of imperialism. Many Marxists working in International Relations make a similar claim. In Italy Gramsci tried to explain that capitalism survived because capitalist elites exercise cultural hegemony. The Frankfurt Schools said the same. It is mostly Gramsci and the Frankfurt School, sometimes collectively called critical theory, that I call cultural Marxism.

Marxism arrived in Brazil mainly in the beginning of the 20th century. Very early then, a communist party was founded there. This communist country was initially very orthodox, following whatever Moscow told them to. However, after WWII and especially after the Military Coup of 1964, Brazilian Marxists started to gravitate towards Gramsci. During the Military Dictatorship, many leftists tried to fight guerrillas, but others simply chose to get into universities, newspapers, churches and other places, and try to overthrow capitalism from there.

In general, I am not a great fan of John Maynard Keynes, but there is a quote from him that I absolutely adore: ““Practical men, who believe themselves to be quite exempt from any intellectual influences, are usually the slaves of some defunct economist”. That’s how I see most Brazilian intellectuals. They are of a superficial brand of Marxism. It would certainly be incorrect to call them Marxist in an orthodox sense, but I understand that they are what Marxism has become: something vaguely anti-establishment, anti-capitalism, in favor of big government and very entitled.

Why is this important for you? Because Brazil is the second largest country in America in population, territory, and economy. That’s why. The economy is a win-win game. An economically free, prosperous Brazil would be good for everyone, not just for Brazilians. But that can only happen if we first defeat the mentality that capitalism is bad and that the state should be an instrument for some vague sort of social justice.

Afternoon Tea: “Confucian Constitutionalism in Imperial Vietnam”

The phantasm of “Oriental despotism” dominating our conventional views of East Asian imperial government has been recently challenged by the scholarship of “Confucian constitutionalism.” To contribute to our full discovery of the manifestations of Confucian constitutionalism in diverse Confucian areas, this paper considers the case of imperial Vietnam with a focus on the early Nguyễn dynasty. The investigation reveals numerous constitutional norms as the embodiment of the Confucian li used to restrain the royal authority, namely the models of ancient kings, the political norms in the Confucian classics, the ancestral precedents, and the institutions of the precedent dynasties. In addition, the paper discovers structuralized forums enabling the scholar-officials to use the norms to limit the royal power, including the royal examination system, the deliberative institutions, the educative institution, the remonstrative institution, and the historical institution. In practical dimension, the paper demonstrates the limitations of these norms and institutions in controlling the ruler due to the lack of necessary institutional independence. At the same time, it also suggests that the relative effectiveness of these norms and institutions could be achieved thanks to the power of tradition. The study finally points out several implications. First, the availability of the constitutional norms and institutions in the tradition is the cultural foundation for the promotion of modern constitutionalism in the present-day Vietnam. Second, the factual material concerning the Vietnamese experiences can hopefully be used for further study of the practice of Confucian constitutionalism in East Asia and further revision of the “Oriental despotism” - based understanding of imperial polity in the region. Third, the findings may also be useful for a more general reflection on pre-modern constitutionalism.

That is from Son Ngoc Bui, a legal scholar at the Chinese University of Hong Kong’s law school. Here is a link.

Afternoon Tea: “Albert Venn Dicey and the Constitutional Theory of Empire”

In the post-1945 world, constitutionalism has transcended the nation-state, with an array of transnational arrangements now manifesting constitutional characteristics — so says a growing number of scholars. This paper reveals an earlier but largely forgotten discourse of transnational constitutionalism: the constitutional theory of the British Empire in the late-nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Focusing on the work of Albert Venn Dicey, the paper shows that, when the Empire was at the height of its power and prestige, British constitutional scholars came to see the Empire as a constitutional order and project. For Dicey, a committed constitutionalist and imperialist, the central dynamic of the imperial constitutional order was balancing British constitutional principles with imperial unity. This paper focuses in particular on parliamentary sovereignty, a constitutional principle that for Dicey was both necessary for and dangerous to the Empire’s integrity. An exercise in intellectual history, the paper rethinks Dicey’s work and the constitutional tradition in which Dicey has played such an integral part, seeking to bring empire back into the picture.

This is from Dylan Lino, a legal theorist at the University of Western Australia’s Law School. Here is the link.

Nightcap

- The day MIT won the Harvard-Yale game Kyle Bonagura, ESPN

- The short, brutish career of the Lion of Punjab Robert Carver, Spectator

- The idea of a borderless world Achille Mbembe, Africa is a Country

- Organised crime and oligarchy in Putin’s Russia Louise Shelley, War on the Rocks

Afternoon Tea: “English Liberties Outside England: Floors, Doors, Windows, and Ceilings in the Legal Architecture of Empire”

We tend to think of global migration and the problem of which legal rights people enjoy as they cross borders as modern phenomena. They are not. The question of emigrant rights was one of the foundational issues in what can be called the constitution of the English empire at the beginning of transatlantic colonization in the seventeenth century. This essay analyzes one strand of this constitutionalism, a strand captured by the resonant term, ‘the liberties and privileges of Englishmen’. Almost every colonial grant – whether corporate charter, royal charter, or proprietary grant – for roughly two dozen imagined, projected, failed, and realized overseas ventures contained a clause stating that the emigrants would enjoy the liberties, privileges and immunities of English subjects. The clause was not invented for transatlantic colonization. Instead, it had medieval roots. Accordingly, royal drafters, colonial grantees, and settlers penned and read these guarantees against the background of traditional interpretations about what they meant.

Soon, however, the language of English liberties and privileges escaped the founding documents, and contests over these keywords permeated legal debates on the meaning and effects of colonization. Just as the formula of English liberties and privileges became a cornerstone of England’s constitutional monarchy, it also became a foundation of the imperial constitution. As English people brought the formula west, they gave it new meanings, and then they returned with it to England and created entirely new problems.

This is from Daniel J. Hulsebosch, a historian at NYU’s Law School. Here is a link.