- One summer in America Eliot Weinberger, London Review of Books

- Death in prison, a short list Ken White, the Atlantic

- The tyranny of the economists Robin Kaiser-Schatzlein, New Republic

- Elites and the economy Donald Schneider, National Affairs

economics

Nightcap

- Inside the liberal elite’s mountain retreat Linda Kinstler, 1843

- How to reform the Economics PhD Tyler Cowen, Marginal Revolution

- Populism’s prophet C Gavin Collins, Quillette

- The Cherokee want their spot in Congress Nick Martin, New Republic

Not all GDP measurement errors are greater than zero!

Bryan Caplan is an optimist. He thinks that economists do many errors in estimating GDP (overall well-being). He is right in the sense that we are missing many dimensions of welfare improvements in the last half-century (see here, here and here). These errors in measurements lead us to hold incorrectly pessimistic views (such as those of Robert Gordon). However, Prof. Caplan seems to argue (I may be wrong) that all measurements problems and errors are greater than zero. In other words, they all cut in favor of omitting things. There are no reasons to believe this. Many measurement problems with GDP data cut the other way – in favor of adding too much (so that the true figures are lower than the reported ones).

Here are two errors of importance (which are in no way exhaustive): household output and adjustments for household size.

Household Output

From the 1910s to the 1940s, married women began to enter moderately the workforce. This trickle became a deluge thereafter. National GDP statistics are really good at capturing the extra output they were hired to produce. However, national GDP statistics cannot net out the production that was foregone: household output.

A married woman in 1940 did produce something: child-rearing, house chores, cooking, allowing the husband to specialize in his work. That output had a value. Once offered the chance to work, married women thought the utility generated from producing “home outputs” was inferior to the utility generated from “market work”. However, the output that is measured is only related to market work. Women entered the labor force and everything they produced was considered a net addition to GDP. In reality, any economist worth his salt is aware that the true improvement in well-being is equal to the increased market output minus the forsaken house output. Thus, in a transition from a “male-labor force” to a “mixed labor force”, you are bound to overestimate output increases.

How big of an issue is this? Well, consider this paper from 1996 in Feminist Economics. In that paper, Barnet Wagman and Nancy Folbre calculate output in both the “household” and “market” sectors. They find that even very small changes in the relative size of these sectors alter growth rates by substantial margins. Another example, which I discussed in this blog post based on articles in the Review of Income and Wealth, is that when you make the adjustment over four decades of available Canadian data, you can find that one quarter of the increase in living standards is eliminated by the proper netting out of the value of non-market output. These are sizable measurement errors that cut in the opposite direction as the one hypothesized by prof. Caplan (and in favor of people like prof. Gordon).

Household Size

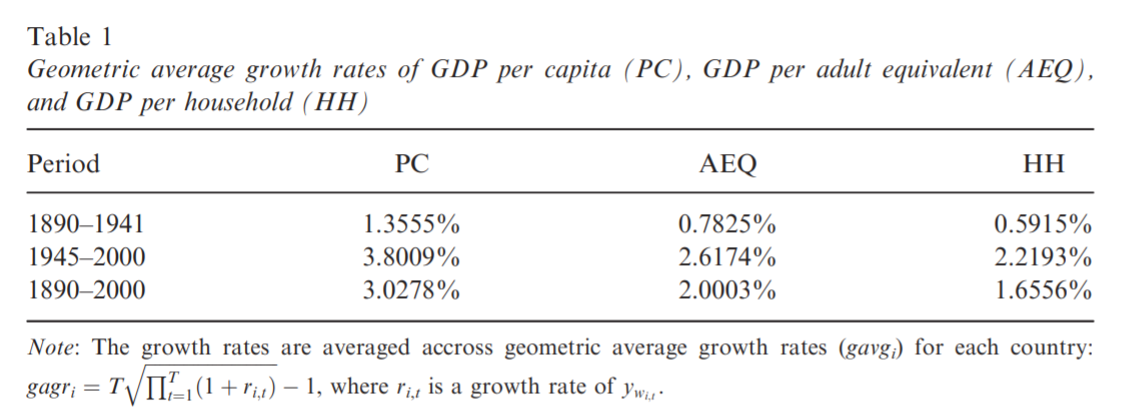

Changes in household sizes also create overestimation problems. Larger households have more economies of scale to exploit than smaller households so that an income of $10,000 per capita in a household of six members is superior in purchasing power than an income of $10,000 per capita in a single-person household. If, over time, you move from large households to small households, you will overestimate economic growth. In an article in the Scottish Journal of Political Economy, I showed that making adjustments for household sizes over time yields important changes in growth rates between 1890 and 2000. Notice, in the table below, that GDP per adult equivalent (i.e. GDP per capita adjusted for household size) is massively different than GDP per capita. Indeed, the adjusted growth rates are reduced by close to two-fifths of their original values over the 1945-2000 period and by a third over the 1890 to 2000 period. This is a massive overestimation of actual improvements in well-being.

A large overestimation

If you assemble these two factors together, I hazard a guess that growth rates would be roughly halved (there is some overlap between the two so that we cannot simply sum them up as errors to correct for – hence my “guess”). This is not negligible. True, there are things that we are not counting as Prof. Caplan notes. We ought to find a way to account for them. However, if they simply wash out the overestimation, the sum of errors may equal zero. If so, those who are pessimistic about the future (and recent past) of economic growth have a pretty sound case. Thus, I find myself unable to share Prof. Caplan’s optimism.

Is minimalism immoral?

I came across a simple but important question on Quora: Is it wrong to aspire to be a minimalist? Doesn’t this negatively affect the country’s GDP?

I see two big lessons here: 1) wise use of metrics requires wisdom… i.e. appropriate interpretation and critical thinking. 2) Maximization is just one version of one part of the whole story. (There are also important questions to ask about what we can expect from others, but I’ll leave that for the comments.)

Readers of NOL should be familiar with the notion that GDP is only an imperfect proxy for well being. But not everyone is so we have to repeat ourselves. There’s what we’re after, and there’s what we can measure, and the two are not the same. GDP is a really clever way to aggregate total production in an economy, but production is only valuable to the extent we’re producing the things that actually improve people’s lives. It’s easy for busy people to confuse a proxy measure for the latent variable we actually care about, so we need someone whispering in the emperor’s ear “the metric is not the mission.”

Economics is easier to describe using the simplifying assumption that people want more stuff. It’s easy to forget that people also want more leisure (and so less work). This is a subtle reappearance of the seen and unseen. We can see when someone gets a cool new car and we can’t see when someone has a fun evening with friends and family. We have to check our bias towards trying to get more stuff and remember that reducing work is another feature of human flourishing.

Fogel on economics and ideology

Many, upon reading the conclusions of economists, believe that economics has an ideological bent. I often respond that this is not the case. True, the “window” of political opinions in economics is narrower but that is largely because the adhesion of economists to methodological individualism precludes certain ideological views that rest on holistic approaches or concepts. However, when you consider more complex situations than “party affiliation”, you will find economists all over the place. They will often cross ideological lines or even have a foot in two antagonistic camps.

Recently, I was reading Robert Fogel’s lectures on the “Slavery debates” which retells the intellectual history of American slavery from U.B. Phillips to … well … Fogel himself. One must remember that Fogel was, and remained from what I can tell, a quite strongly left-leaning economist for most of his life (see here). As such, it is hard to consider Fogel as an ideologue preaching for free market economics. Yet, in the lectures, Fogel (p.19) makes a point that supports the contention that I often make regarding economists and ideology that I believe must be shared:

The ability to view Phillips (NDLR: the dominant interpretation of slavery pre-1960) in a new light was facilitated by the sudden intrusion of a large corps of economists into the slavery debates during the 1960s. This intrusion was welcomed by neither the defenders of the Phillips tradition nor the neoabolitionist school led by Stampp (NDLR: Kenneth Stampp, author of The Peculiar Institution). The cliometricians, as they were called, refused to be bound by the established rules of engagement, and they blithely crossed ideological wires in a manner that perplexed and exasperated traditional historians on both sides of the ideological divide.

Given that the source of this quotation is Fogel, I admit that I am particularly fond of this passage. Maybe the distrust towards economists is because economists can be both friend and foes to established interlocutors in a given discussion.

Economists vs. The Public

Economics is the dismal science, as Thomas Carlyle infamously said, reprising John Stuart Mill for defending the abolishment of slavery in the British Empire. But if being a “dismal science” includes respecting individual rights and standing up for early ideas of subjective, revealed, preferences – sign me up! Indeed, British economist Diane Coyle wisely pointed out that we should probably wear the charge as a badge of honor.

Non-economists, quite wrongly, attack economics for considering itself the “Queen of the Social Science”, firing up slurs, insults and contours: Economism, economic imperialism, heartless money-grabbers. Instead, I posit, one of our great contributions to mankind lies in clarity and, quoting Joseph Persky “an acute sensitivity to budget constraints and opportunity costs.”

Now, clarity requires one to be specific. To clearly define the terms of use, and refrain from the vague generality of unmeasurable and undefinable concepts so common among the subjects over whom economics is the queen. When economists do their best to be specific, they sometimes use terms that also have a colloquial meaning, seriously confusing the layman while remaining perfectly clear for those of us who “speak the language”. I realize the irony here, and therefore attempt my best to straighten out some of these things, giving the examples of 1) money and 2) investments.

An age-old way to see this mismatch is measuring the beliefs held by the vast majority of economists and the general public (Browsing the Chicago IGM surveys gives some examples of this). Bryan Caplan illustrates this very well in his 2006 book The Myth of the Rational Voter:

Noneconomists and economists appear to systematically disagree on an array of topics. The SAEE [“Survey of Americans and Economists on the Economy”] shows that they do. Economists appear to base their beliefs on logic and evidence. The SAEE rules out the competing theories that economists primarily rationalize their self-interest or political ideology. Economists appear to know more about economics than the public. (p. 83)

Harvard Professor Greg Mankiw lists some well-known positions where the beliefs of economists and laymen diverge significantly (rent control, tariffs, agricultural subsidies and minimum wages). The case I, Mankiw, Caplan and pretty much any economist would make is one of appeal to authority: if people who spent their lives studying something overwelmingly agree on the consequences of a certain position within their area of expertise (tariffs, minimum wage, subsidies etc) and in stark opposition to people who at best read a few newspapers now and again, you may wanna go with the learned folk. Just sayin’.

Caplan even humorously compared the ‘appeal to authority’ of other professions to economists:

In principle, experts could be mistaken instead of the public. But if mathematicians, logicians, or statisticians say the public is wrong, who would dream of “blaming the experts”? Economists get a lot less respect. (p. 53)

Money, Wealth, Income

The average public confusingly uses all of these terms interchangeably. A rich person has ‘money’, and being rich is either a reference to income or to wealth, or sometimes both – sometimes even in the same sentence. Economists, being specialists, should naturally have a more precise and clear meaning attached to these words. For us Income refers to a flow of purchasing power over a certain period (=wage, interest payments), whereas Wealth is a stock of assets or “fixed” purchasing power; my monthly salary is income whereas the ownership of my house is wealth (the confusion here may be attributable to the fact that prices of wealth – shares, house prices etc – can and often do change over short periods of time, and that people who specialize in trading assets can thereby create income for themselves).

‘Money’, which to the average public means either wealth or income, is to the economist simply the metric we use, the medium of exchange, the physical/digital object we pass forth and back in order to clear transactions; representing the unit of account, the thing in which we calculate money (=dollars). That little green-ish piece of paper we instantly think of as ‘money’. To illustrate the difference: As a poor student, I may currently have very little income and even negative wealth, but I still possess money with which I pay my rent and groceries. In the same way, Bill Gates with massive amounts of wealth can lack ‘money’, simply meaning that he would need to stop by the ATM.

Investment

A lot like money, the practice of calling everything an ‘investment’ is annoying to most economists: the misuse drives us nuts! We’re commonly told that some durable consumption good was an investment, simply because I use it often; I’ve had major disagreements friends over the investment or consumption status of a) cars, b) houses, c) clothes, and d) every other object under the sun. Much like ‘money’, ‘investment’ to the general public seem to mean anything that gives you some form of benefit or pleasure. Or it may more narrowly mean buying financial assets (stocks, shares, derivatives…). For economists, it means something much more specific. Investopedia brilliantly explains it: The definition has two components; first, it generates an income (or is hoped to appreciate in value); secondly, it is not consumed today but used to create wealth:

An investment is an asset or item that is purchased with the hope that it will generate income or will appreciate in the future. In an economic sense, an investment is the purchase of goods that are not consumed today but are used in the future to create wealth.

This definition clearly shows why clothes, yoga mats and cars are not investments; they are clearly consumption goods that, although giving us lots of joy and benefits, generates zero income, won’t appreciate and is gradually worn out (i.e. consumed). Almost as clearly, houses (bought to live in) aren’t investments (newsflash a decade after the financial crisis); they generate no income for the occupants (but lots of costs!) and deteriorates over time as they are consumed. The only confusing element here is the appreciation in value, which is an abnormal feature of the last say four decades: the general trend in history has been that housing prices move with price inflation, i.e. don’t lose value other than through deterioration. In fact, Adam Smith said the very same thing about housing as an investment:

A dwelling-house, as such, contributed nothing to the revenue of its inhabitant; and though it is no doubt extremely useful to him, it is as his cloaths and household furniture are useful to him, which however make a part of his expence, and not his revenue. (AS, Wealth of Nations, II.1.12)

Cars are even worse, depreciating significantly the minute you leave the parking lot of the dealership. Where the Investopedia definition above comes up short is for business investments; when my local bakery purchases a new oven, it passes the first criteria (generates incomes, in terms of bread I can sell), but not the second, since it is generally consumed today. Some other tricky example are cases where political interests attempt to capture the persuasive language of economists for their own purposes: that we need to invest in our future, either meaning non-fossil fuel energy production, health care or some form of publicly-funded education. It is much less clear that these are investments, since they seldom generate an income and are more like extremely durable consumption goods (if they do classify on some kind of societal level, they seem like very bad ones).

In summary, economists think of investments as something yielding monetary returns in one way or another. Either directly like interest paid on bonds or deposits (or dividends on stocks) or like companies transforming inputs into revenue-generating output. It is, however, clear that most things the public refer to as investments (cars, clothes, houses) are very far from the economists’ understanding.

Economists and the general public often don’t see eye-to-eye. But improving the communication between the two should hopefully allow them to – indeed, the clarity with which we do so is our claim to fame in the first place.

Revised version of blog post originally published in Nov 2016 on Life of an Econ Student as a reflection on Establishment-General Public Divide.

Low-Quality Publications and Academic Competition

In the last few days, the economics blogosphere (and twitterverse) has been discussing this paper in the Journal of Economic Psychology. Simply put, the article argues that economists discount “bad journals” so that a researcher with ten articles in low-ranked and mid-ranked journals will be valued less than a researcher with two or three articles in highly-ranked journals.

Some economists, see notably Jared Rubin here, made insightful comments about this article. However, there is one comment by Trevon Logan that gives me a chance to make a point that I have been mulling over for some time. As I do not want to paraphrase Trevon, here is the part of his comment that interests me:

many of us (note: I assume he refers to economists) simply do not read and therefore outsource our scholarly opinions of others to editors and referees who are an extraordinarily homogeneous and biased bunch

There are two interrelated components to this comment. The first is that economists tend to avoid reading about minute details. The second is that economists tend to delegate this task to gatekeepers of knowledge. In this case, this would be the editors of top journals. Why do economists act as such? More precisely, what are the incentives to act as such? After, as Adam Smith once remarked, the professors at Edinburgh and Oxford were of equal skill but the former produced the best seminars in Europe because their incomes depended on registrations and tuition while the latter relied on long-established endowments. Same skills, different incentives, different outcomes.

My answer is as such: the competition that existed in the field of economics in the 1960s-1980s has disappeared. In “those” days, the top universities such as Princeton, Harvard, MIT and Yale were a more or less homogeneous group in terms of their core economics. Lets call those the “incumbents”. They faced strong contests from the UCLA, Chicago, Virginia and Minnesota. These challengers attacked the core principles of what was seen as the orthodoxy in antitrust (see the works of Harold Demsetz, Armen Alchian, Henry Manne), macroeconomics (Lucas Paradox, Islands model, New Classical Economics), political economy (see the works of James Buchanan, Gordon Tullock, Elinor Ostrom, Albert Breton, Charles Plott) and microeconomics (Ronald Coase). These challenges forced the discipline to incorporate many of the insights into the literature. The best example would be the New Keynesian synthesis formulated by Mankiw in response to the works of people like Ed Prescott and Robert Lucas. In those days, “top” economists had to respond to articles published in “lower-ranked” journals such as Economic Inquiry, Journal of Law and Economics and Public Choice (all of which have risen because they were bringing competition – consider that Ronald Coase published most of his great pieces in the JL&E).

In that game, economists were checking one another and imposing discipline upon each other. More importantly, to paraphrase Gordon Tullock in his Organization of Inquiry, their curiosity was subjected to social guidance generated from within the community:

He (the economist) is normally interested in the approval of his peers and and hence will usually consciously shape his research into a project which will pique other scientists’ curiosity as well as his own.

Is there such a game today? If in 1980 one could easily answer “Chicago” to the question of “which economics department challenges that Harvard in terms of research questions and answers”, things are not so clear today. As research needs to happen within a network where the marginal benefits may increase with size (up to a point), where are the competing networks in economics?

And there is my point, absent this competition (well, I should not say absent – it is more precise to speak of weaker competition) there is no incentive to read, to invest other fields for insights or to accept challenges. It is far more reasonable, in such a case, to divest oneself from the burden of academia and delegate the task to editors. This only reinforces the problem as the gatekeepers get to limit the chance of a viable network to emerge.

So, when Trevon bemoans (rightfully) the situation, I answer that maybe it is time that we consider how we are acting as such because the incentives have numbed our critical minds.

On the rift between economics and everything else

The line is often heard: economists are “scientific imperialists” (i.e. they seek to invade other fields of social science) jerks. All they try to do is “fit everything inside the model”. I have this derisive sneer at economists very often. I have also heard economists say “who cares, they’re a bunch of historians” (this is the one I hear most often given my particular field of research, but I have heard variations involving sociologists and anthropologists).

To be fair, I never noticed the size rift. For years now, I have been waltzing between economics and history (and tried my hand at journalism for some time) which meant that I was waltzing between economic theory and a lot of other fields. The department I was a part of at the London School of Economics was a rich set of quantitative and qualitative folks who mixed history of ideas, economics, economic history and social history. To top it all, I managed to find myself generally in the company of attorneys and legal scholars (don’t ask why, it still eludes me). It was hard to feel a big rift in that environment. I knew there was a rift. I just never realized how big it was until a year ago (more or less).

There is, however, something that annoys me: the contempt appears to be self-reinforcing. Elsewhere on this blog (here and here) (and in a forthcoming book chapter in a textbook on how to do economic history), I have explained that economists have often ventured into certain topics with a lack of care for details. True, there must be some abstraction of details (not all details are useful), but there is an optimal quantity of details. And our knowledge grows, the quantity of details necessary to answering each question (because the scientific margin is increasingly specialized) should grow. And so should the number (and depth) of nuances we make to answer a question. There is a tendency among economists to treat a question outside the usual realm of economics and ignore the existing literature (thus either rushing through an open door or stepping in a minefield without knowing it). The universe is collapsed into the model and, even when it yields valuable insights, other (non-econs) contributors are ignored. That’s when the non-econs counter that economists are arrogant and that they try to force everything into a mold rather than change the mold when it does not apply. However, the reply has often been to ignore the economists or criticize strawmen versions of their argument. Perceived as contemptuous, the economists feel that they can safely ignore all others.

The problem is that this is a reinforcing loop: a) the economists are arrogant; b) non-economists respond by dismissing the economists and ridiculing their assumptions; c) the economists get more arrogant. The cycle persists. I struggle to see how to break this cycle, but I see value in breaking it. Elsewhere, I have made such a case when I reviewed a book (towards which I was hostile) on Canadian economic history. Here is what I said for the sake of showcasing the value of breaking the vicious circle of ignoring both sides:

These scholars (those who have been ignored by non-economists) could have easily derived the same takeaways as Sweeny. Individuals can and do engage in rent-seeking, which economists define as the process through which unearned gains are obtained by manipulating the political and social environment. This could be observed in attempts to shape narratives in the public discourse. According primacy to the biases of sources is a recognition that there can be rent-seeking in the form of actors seeking to generate a narrative to reinforce a particular institutional arrangement and allow it to survive. This explanation is well in line with neoclassical economics.

This point is crucial. It shows a failing on both sides of the debate. Economists and historians favorable to “rational choice” have failed to engage scholars like Sweeny. Often, they have been openly contemptuous. The literature has evolved in separate circles where researchers only speak to their fellow circle members. This has resulted in an inability to identify the mutual gains of exchange. The insights and meticulous treatments of sources by scholars like Sweeny are informative for those economists who consider rational choice as if the choosers were humans, with all their flaws and limitations, rather than mechanistic utility-maximizing machines with perfect foresight (which is a strawman often employed to deride the use of economics in historical debates) . In reverse, the rich insights provided by rational choice theorists could guide historians in elucidating complex social interactions with a parsimony of assumptions. Without interaction, both groups loose and resolutions remain elusive.

See, as a guy who likes economics, I think that trade is pretty great. More importantly, I think that trade between heterogeneous groups (or different individuals) is even greater because it allows for specialization that increases the value (and quantity) of outputs. I see the benefits of trade here, so why is this “circle of contempt” perpetuating so relentlessly?

Can’t we just all pick the 100$ bill on the sidewalk?

Nightcap

- Black African Tudors of England Jonathan Carey, Atlas Obscura

- What can Marx and Smith teach us? Felix Martin, New Statesman

- The history of Leonardo’s Salvator Mundi Morgan Meis, the Easel

- Goddess of Anarchy Elaine Elinson, Los Angeles Review of Books

If causality matters, should the media talk about mass shootings?

My answer to that question is “maybe not” or at the very least “not as much”. Given the sheer amount of fear that can be generated by a shooting, it is understandable to be shocked and the need to talk about it is equally understandable. However, I think this might be an unfortunate opportunity to consider the incentives at play.

I assume that criminals, even crazy ones, are relatively rational. They weigh the pros and cons of potential targets, they assess the most efficient tool or weapon to accomplish the objectives they set etc. That entails that, in their warped view of the world, there are benefits to committing atrocities. In some instances, the benefit is pure revenge as was the case in one of the famous shooting in my hometown of Montreal (i.e. a university professor decided to avenge himself of the slights caused by other professors). In other instances, the benefit is defined in part by the attention that the violent perpetrator attracts for himself. This was the case of another infamous shooting in Montreal where the killer showed up at an engineering school to kill 14 other students and staff. He committed suicide and also left a suicide statement that read like a garbled political manifesto. In other words, killers can be trying to “maximize” media hits.

This “rational approach” to mass shootings opens the door to a question about causality: is the incidence of mass shootings determining the number of media hits or is the number of media hits determining the incidence of mass shootings. In a recent article in the Journal of Public Economics, the possibility of the latter causal link has been explored with regards to terrorism. Using the New York Times‘ coverage of some 60,000 terrorist attacks in 201 countries over 43 years, Michael Jetter used the exogenous shock caused by natural disasters to study they reduced the reporting of terrorist attacks and how this, in turn, reduced attention to terrorism. That way, he could arrive at some idea (by the negative) of causality. He found that one New York Times article increased attacks by 1.4 in the following three weeks. Now, this applies to terrorism, but why would it not apply to mass shooters? After all, there are very similar in their objectives and methods – at the very least with regards to the shooters who seek attention.

If the causality runs in the direction suggested by Jetter, then the full-day coverage offered by CNN or NBC or FOX is making things worse by increasing the likelihood of an additional shooting. For some years now, I have been suggesting this possibility to journalist friends of mine and arguing that maybe the best way to talk about terrorism or mass shooters is to move them from the front page of a newspaper to a one-inch box on page 20 or to move the mention from the interview to the crawler at the bottom. In each discussion, my claim about causality is brushed aside with either incredulity at the logic and its empirical support or I get something like “yes, but we can’t really not talk about it”. And so, the thinking ends there. However, I am quite willing to state that its time for media outlets to deeply reflect upon their role and how to best accomplish the role they want. And that requires thinking about causality and accepting that “splashy” stories may be better left ignored.

On the point of quantifying in general and quantifying for policy purposes

Recently, I stumbled on this piece in Chronicle by Jerry Muller. It made my blood boil. In the piece, the author basically argues that, in the world of education, we are fixated with quantitative indicators of performance. This fixation has led to miss (or forget) some important truths about education and the transmission of knowledge. I wholeheartedly disagree because the author of the piece is confounding two things.

We need to measure things! Measurements are crucial to our understandings of causal relations and outcomes. Like Diane Coyle, I am a big fan of the “dashboard” of indicators to get an idea of what is broadly happening. However, I agree with the authors that very often the statistics lose their entire meaning. And that’s when we start targeting them!

Once we know that this variable becomes the object of target, we act in ways that increase this variable. As soon as it is selected, we modify our behavior to achieve fixed targets and the variable loses some of its meaning. This is also known as Goodhart’s law whereby “when a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure” (note: it also looks a lot like the Lucas critique).

Although Goodhart made this point in the context of monetary policy, it applies to any sphere of policy – including education. When an education department decides that this is the metric they care about (e.g. completion rates, minority admission, average grade point, completion times, balanced curriculum, ratio of professors to pupils, etc.), they are inducing a change in behavior which alters the significance carried by this variable. This is not an original point. Just go to google scholar and type “Goodhart’s law and education” and you end up with papers such as these two (here and here) that make exactly the point I am making here.

In his Chronicle piece, Muller actually makes note of this without realizing how important it is. He notes that “what the advocates of greater accountability metrics overlook is how the increasing cost of college is due in part to the expanding cadres of administrators, many of whom are required to comply with government mandates“(emphasis mine).

The problem he is complaining about is not metrics per se, but rather the effects of having policy-makers decide a metric of relevance. This is a problem about selection bias, not measurement. If statistics are collected without an intent to be a benchmark for the attribution of funds or special privileges (i.e. that there are no incentives to change behavior that affects the reporting of a particular statistics), then there is no problem.

I understand that complaining about a “tyranny of metrics” is fashionable, but in that case the fashion looks like crocs (and I really hate crocs) with white socks.

More simple economic truths I wish more people understood

There are only four ways to spend money:

- You spend your money with yourself.

- You spend your money with others.

- You spend other’s money with yourself.

- You spend other’s money with others.

Just think about it for one second and you will agree: these are the only possible ways to spend money.

The best way to spend money is to spend your money with yourself. The worst is when you spend other’s money with others.

When you spend your money with yourself, you know how much money you have and what your needs are.

When you spend your money with others, you know how much money you have but you don’t know as well what other’s needs are.

When you spend other’s money with yourself you know your needs but you don’t know how much money you can actually spend. In a situation like this, some people will shy away from spending much money (when they actually could) and will end up not totally satisfied. Other people will have no problem like that and will spend as crazy, not noticing that they are spending too much. It doesn’t matter what kind of person you are: the fact is that this is not a good way to spend money.

When you spend other’s money with others you have the worst case scenario: you don’t know other’s needs as well as they know and you also don’t have a clear grasp of how much money you can actually spend.

In a true liberal capitalist society, the majority of the money is spent by individuals on their own needs. The more a society drifts away from this ideal, the more people spend money that is not actually theirs on other people. The more money is misused.

The government basically spend money is not theirs on other people. That’s why government spending is usually bad. Even the most well-meaning government official, more in line with your personal beliefs, will probably not spend your money as well as you could yourself.

Simple economics I wish more people understood

Economics comes from the Greek “οίκος,” meaning “household” and “νęμoμαι,” meaning “manage.” Therefore, in its more basic sense, economy means literally “rule of the house.” It applies to the way one manages the resources one has in their house.

Everyone has access to limited resources. It doesn’t matter if you are rich, poor, or middle class. Even the richest person on Earth has limited resources. Our day has only 24 hours. We only have one body. This body starts to decay very early in our lives. Even with modern medicine, we don’t get to live much more than 100 years.

The key of economics is how well we manage our limited resources. We need to make the best with the little we are given.

For most of human history, we were very poor. We had access to very limited resources, and we were not particularly good at managing them. We became much better in managing resources in the last few centuries. Today we can do much more with much less.

Value is a subjective thing. One thing has value when you think this thing has value. You may value something that I don’t.

We use money to exchange value. Money in and of itself can have no value at all. It doesn’t matter. The key of money is its ability to transmit information: I value this and I don’t value that.

Of course, many things can’t be valued in money. At least for most people. But it doesn’t change the fact that money is a very intelligent way to attribute value to things.

The economy cannot be managed centrally by a government agency. We have access to limited resources. Only we, individually, can judge which resources are more necessary for us in a given moment. Our needs can change suddenly, without notice. You can be saving money for years to buy a house, only to discover you will have to spend this money on a medical treatment. It’s sad. It’s even tragic. But it is true. If the economy is managed centrally, you have to transmit information to this central authority that your plans have changed. But if we have a great number of people changing plans every day, then this central authority will inevitably be loaded. The best judge of how to manage your resources is yourself.

We can become really rich as a society if we attribute responsibility for each person on how we manage our resources. If each one of us manages their resources to the best of their knowledge and abilities, we will have the best resource management possible. We will make the best of the limited resources we have.

Economics has a lot to do with ecology. They share the Greek “οίκος” which, again, means “household.” This planet is our house. The best way to take care of our house is to distribute individual responsibility over individual management of individual pieces of this Earth. No one can possess the whole Earth. But we can take care of tiny pieces we are given responsibility over.

On Borjas, Data and More Data

I see my craft as an economic historian as a dual mission. The first is to answer historical question by using economic theory (and in the process enliven economic theory through the use of history). The second relates to my obsessive-compulsive nature which can be observed by how much attention and care I give to getting the data right. My co-authors have often observed me “freaking out” over a possible improvement in data quality or be plagued by doubts over whether or not I had gone “one assumption too far” (pun on a bridge too far). Sometimes, I wish more economists would follow my historian-like freakouts over data quality. Why?

Because of this!

In that paper, Michael Clemens (whom I secretly admire – not so secretly now that I have written it on a blog) criticizes the recent paper produced by George Borjas showing the negative effect of immigration on wages for workers without a high school degree. Using the famous Mariel boatlift of 1980, Clemens basically shows that there were pressures on the US Census Bureau at the same time as the boatlift to add more black workers without high school degrees. This previously underrepresented group surged in importance within the survey data. However since that underrepresented group had lower wages than the average of the wider group of workers without high school degrees, there was an composition effect at play that caused wages to fall (in appearance). However, a composition effect is also a bias causing an artificial drop in wages and this drove the results produced by Borjas (and underestimated the conclusion made by David Card in his original paper to which Borjas was replying).

This is cautionary tale about the limits of econometrics. After all, a regression is only as good as the data it uses and suited to the question it seeks to answer. Sometimes, simple Ordinary Least Squares are excellent tools. When the question is broad and/or the data is excellent, an OLS can be a sufficient and necessary condition to a viable answer. However, the narrower the question (i.e. is there an effect of immigration only on unskilled and low-education workers), the better the method has to be. The problem is that the better methods often require better data as well. To obtain the latter, one must know the details of a data source. This is why I am nuts over data accuracy. Even small things matter – like a shift in the representation of blacks in survey data – in these cases. Otherwise, you end up with your results being reversed by very minor changes (see this paper in Journal of Economic Methodology for examples).

This is why I freak out over data. Maybe I can make two suggestions about sharing my freak-outs.

The first is to prefer a skewed ratio of data quality to advanced methods (i.e. simple methods with crazy-data). This reduces the chances of being criticized for relying on weak assumptions. The second is to take a leaf out of the book of the historians. While historians are often averse to advantaged data techniques (I remember a case when I had to explain panel data regressions to historians which ended terribly for me), they are very respectful of data sources. I have seen historians nurture datasets for years before being willing to present them. When published, they generally stand up to scrutiny because of the extensive wealth of details compiled.

That’s it folks.

On doing economic history

I admit to being a happy man. While I am in general a smiling sort of fellow, I was delightfully giggling with joy upon hearing that another economic historian (and a fellow Canadian from the LSE to boot), Dave Donaldson, won the John Bates Clark medal. I dare say that it was about time. Nonetheless I think it is time to talk to economists about how to do economic history (and why more should do it). Basically, I argue that the necessities of the trade require a longer period of maturation and a considerable amount of hard work. Yet, once the economic historian arrives at maturity, he produces long-lasting research which (in the words of Douglass North) uses history to bring theory to life.

Economic History is the Application of all Fields of Economics

Economics is a deductive science through which axiomatic statements about human behavior are derived. For example, stating that the demand curve is downward-sloping is an axiomatic statement. No economist ever needed to measure quantities and prices to say that if the price increases, all else being equal, the quantity will drop. As such, economic theory needs to be internally consistent (i.e. not argue that higher prices mean both smaller and greater quantities of goods consumed all else being equal).

However, the application of these axiomatic statements depends largely on the question asked. For example, I am currently doing work on the 19th century Canadian institution of seigneurial tenure. In that work, I question the role that seigneurial tenure played in hindering economic development. In the existing literature, the general argument is that the seigneurs (i.e. the landlords) hindered development by taxing (as per their legal rights) a large share of net agricultural output. This prevented the accumulation of savings which – in times of imperfect capital markets – were needed to finance investments in capital-intensive agriculture. That literature invoked one corpus of axiomatic statements that relate to capital theory. For my part, I argue that the system – because of a series of monopoly rights – was actually a monopsony system through the landlords restrained their demand for labor on the non-farm labor market and depressed wages. My argument invokes the corpus of axioms related to industrial organization and monopsony theory. Both explanations are internally consistent (there are no self-contradictions). Yet, one must be more relevant to the question of whether or not the institution hindered growth and one must square better with the observed facts.

And there is economic history properly done. It tries to answer which theory is relevant to the question asked. The purpose of economic history is thus to find which theories matter the most.

Take the case, again, of asymetric information. The seminal work of Akerlof on the market for lemons made a consistent theory, but subsequent waves of research (notably my favorite here by Eric Bond) have showed that the stylized predictions of this theory rarely materialize. Why? Because the theory of signaling suggests that individuals will find ways to invest in a “signal” to solve the problem. These are two competing theories (signaling versus asymetric information) and one seems to win over the other. An economic historian tries to sort out what mattered to a particular event.

Now, take these last few paragraphs and drop the words “economic historians” and replace them by “economists”. I believe that no economist would disagree with the definition of the tasks of the economist that I offered. So why would an economic historian be different? Everything that has happened is history and everything question with regards to it must be answered through sifting for the theories that is relevant to the event studied (under the constraint that the theory be consistent). Every economist is an economic historian.

As such, the economic historian/economist must use advanced tools related to econometrics: synthetic controls, instrumental variables, proper identification strategies, vector auto-regressions, cointegration, variance analysis and everything you can think of. He needs to do so in order to answer the question he tries to answer. The only difference with the economic historian is that he looks further back in the past.

The problem with this systematic approach is the efforts needed by practitioners. There is a need to understand – intuitively – a wide body of literature on price theory, statistical theories and tools, accounting (for understanding national accounts) and political economy. This takes many years of training and I can take my case as an example. I force myself to read one scientific article that is outside my main fields of interest every week in order to create a mental repository of theoretical insights I can exploit. Since I entered university in 2006, I have been forcing myself to read theoretical books that were on the margin of my comfort zone. For example, University Economics by Allen and Alchian was one of my favorite discoveries as it introduced me to the UCLA approach to price theory. It changed my way of understanding firms and the decisions they made. Then reading some works on Keynesian theory (I will confess that I have never been able to finish the General Theory) which made me more respectful of some core insights of that body of literature. In the process of reading those, I created lists of theoretical key points like one would accumulate kitchen equipment.

This takes a lot of time, patience and modesty towards one’s accumulated stock of knowledge. But these theories never meant anything to me without any application to deeper questions. After all, debating about the theory of price stickiness without actually asking if it mattered is akin to debating with theologians about the gender of angels (I vote that they are angels and since these are fictitious, I don’t give a flying hoot’nanny). This is because I really buy in the claim made by Douglass North that theory is brought to life by history (and that history is explained by theory).

On the Practice of Economic History

So, how do we practice economic history? The first thing is to find questions that matter. The second is to invest time in collecting inputs for production.

While accumulating theoretical insights, I also made lists of historical questions that were still debated. Basically, I made lists of research questions since I was an undergraduate student (not kidding here) and I keep everything on the list until I have been satisfied by my answer and/or the subject has been convincingly resolved.

One of my criteria for selecting a question is that it must relate to an issue that is relevant to understanding why certain societies are where there are now. For example, I have been delving into the issue of the agricultural crisis in Canada during the early decades of the 19th century. Why? Because most historians attribute (wrongly in my opinion) a key role to this crisis in the creation of the Canadian confederation, the migration of the French-Canadians to the United States and the politics of Canada until today. Another debate that I have been involved in relates to the Quiet Revolution in Québec (see my book here) which is argued to be a watershed moment in the history of the province. According to many, it marked a breaking point when Quebec caught up dramatically with the rest of Canada (I disagreed and proposed that it actually slowed down a rapid convergence in the decade and a half that preceded it). I picked the question because the moment is central to all political narratives presently existing in Quebec and every politician ushers the words “Quiet Revolution” when given the chance.

In both cases, they mattered to understanding what Canada was and what it has become. I used theory to sort out what mattered and what did not matter. As such, I used theory to explain history and in the process I brought theory to life in a way that was relevant to readers (I hope). The key point is to use theory and history together to bring both to life! That is the craft of the economic historian.

The other difficulty (on top of selecting questions and understanding theories that may be relevant) for the economic historian is the time-consuming nature of data collection. Economic historians are basically monks (and in my case, I have both the shape and the haircut of friar Tuck) who patiently collect and assemble new data for research. This is a high fixed cost of entering in the trade. In my case, I spent two years in a religious congregation (literally with religious officials) collecting prices, wages, piece rates, farm data to create a wide empirical portrait of the Canadian economy. This was a long and arduous process.

However, thanks to the lists of questions I had assembled by reading theory and history, I saw the many steps of research I could generate by assembling data. Armed with some knowledge of what I could do, the data I collected told me of other questions that I could assemble. Once I had finish my data collection (18 months), I had assembled a roadmap of twenty-something papers in order to answer a wide array of questions on Canadian economic history: was there an agricultural crisis; were French-Canadians the inefficient farmers they were portrayed to be; why did the British tolerate catholic and French institutions when they conquered French Canada; did seigneurial tenure explain the poverty of French Canada; did the conquest of Canada matter to future growth; what was the role of free banking in stimulating growth in Canada etc.

It is necessary for the economic historian to collect a ton of data and assemble a large base of theoretical knowledge to guide the data towards relevant questions. For those reasons, the economic historian takes a longer time to mature. It simply takes more time. Yet, once the maturation is over (I feel that mine is far from being over to be honest), you get scholars like Joel Mokyr, Deirdre McCloskey, Robert Fogel, Douglass North, Barry Weingast, Sheilagh Ogilvie and Ronald Coase (yes, I consider Coase to be an economic historian but that is for another post) who are able to produce on a wide-ranging set of topics with great depth and understanding.

Conclusion

The craft of the economic historian is one that requires a long period of apprenticeship (there is an inside joke here, sorry about that). It requires heavy investment in theoretical understanding beyond the main field of interest that must be complemented with a diligent accumulation of potential research questions to guide the efforts at data collection. Yet, in the end, it generates research that is likely to resonate with the wider public and impact our understanding of theory. History brings theory to life indeed!