- West Coast jazz revival Ted Gioia, City Journal

- Augustine’s Cogito David Potts, Policy of Truth

- Iraq: A failure of ideas Sam Roggeveen, War on the Rocks

- Confucian patriarchy and the allure of communism in China Alan Roberts, Not Even Past

communism

RCH: Grenada and the polarization of democratic society

I’ve been so busy enjoying Jacques’ series on immigration that I almost forgot to link to my latest over at RealClearHistory. A slice:

Grenada is a small island in the Caribbean about 100 miles to the north of Venezuela. The island gained its independence from the United Kingdom in 1974 and held elections that year. In 1979, communists violently overthrew the democratically elected government of Grenada and installed a dictatorship. By 1983, infighting between communist factions produced yet another coup, and the leader of the first coup was murdered and replaced by a more hardline Marxist faction (the New Joint Endeavor for Welfare, Education, and Liberation, or New JEWEL, movement). Pleas from democrats inside Grenada were heard by Reagan and he ordered the invasion of Grenada, which was bolstered by troops from most of Grenada’s neighbors. Today, Oct. 25 is celebrated in Grenada as Thanksgiving Day, in honor of the United States coming to the defense of Grenada’s fledgling democracy.

Please, read the rest.

Nightcap

- Maggie Thatcher still owns the Left John Harris, New Statesman

- Stalinist Terror, Communist Prisons Patrick Kurp, Los Angeles Review of Books

- 1968 and the Irony of History Michael Mandelbaum, American Interest

- When Populism First Eclipsed the Liberal Elite Michael Massing, New York Review of Books

Sunday reading: Bertrand Russell

We have a lot of fresh faces in my philosophy club this semester. On one hand, the new perspectives remind our old heads about some of the basic questions we studied when we first arrived at university, and it’s nice to introduce new students to philosophy; on the other, it makes us behave like a wolf pack, moving at the pace of the slowest member. Sometimes, I want to be an elitist and focus on more complex areas, utilizing the knowledge of our most experienced members. This would mean we lose all of our new members. Ultimately, semester after semester, keeping a high membership (and keeping students participating) always proves to be more important.

This fall I assigned Bertrand Russell’s Problems of Philosophy, as an easy intro text. As he introduces ideas, he injects his own interpretations and potential solutions, and I find I usually disagree with him. However, Russell is great at moving between analytic argument and simple, digestible prose, so I started seeking his other writing out, as one of the canonical popularizers. Here is an essay I thought I’d share, on his meeting with Lenin, Trotsky and Maksim Gorky, when, as a self-identified Communist seeking out the new post-capitalist order, he inadvertently ended up completely disillusioned with the “Bolshevik religion.” He would publish The Practice and Theory of Bolshevism shortly after in 1920, condemning the historical materialist philosophy and system he saw just three years after the October Revolution.

Russell remained somewhere between a social democrat and a democratic socialist throughout his life (e.g., his 1932 “In Praise of Idleness” on libcom.org), but a vocal critic of Soviet repression. He was also a devout pacifist, which explains his early infatuation with the Russian political party which advocated an end to WWI. He died of influenza in 1970 after appealing to the United Nations to investigate the Pentagon for war crimes in South Vietnam.

From his article on meeting Lenin:

Perhaps love of liberty is incompatible with wholehearted belief in a panacea for all human ills. If so, I cannot but rejoice in the skeptical temper of the Western world. I went to Russia believing myself a communist; but contact with those who have no doubts has intensified a thousandfold my own doubts, not only of communism, but of every creed so firmly held that for its sake men are willing to inflict widespread misery.

Is Socialism Really Revolutionary?

A central feature of Karl Marx’s thought is its teleological character: the world walks inexorably towards communism. It is not a question of choices. It is not a question of individual decisions. Communism is simply the direction in which the world walks. Capitalism will collapse not because of some external force, but because of its own internal contradictions (centrally the exploitation of the workers).

I don’t know exactly what History classes are like in other countries, but in basically all my academic trajectory I was bombarded with some version of Marxism. Particularly as far as my country was concerned, the question was not whether a socialist revolution would happen, but why it was taking so long! Looking at events in the past, the reading was as follows: the bourgeoisie overthrew the Old Regime in the French Revolution. At that time the bourgeoisie were revolutionaries (and therefore left-wing). However, overthrowing the monarchy and establishing a constitutional government, the bourgeois became advocates of the new order (and therefore, reactionary, or right-wing). Socialists have become the new revolutionaries, the new left, the new radicals.

This way of seeing history has a Hegelian background: there are no absolutes. History moves through a process of thesis, antithesis, and synthesis. History’s god is learning to be a god. I’ve written earlier here about how this kind of relativistic view does not stand on its own terms. Now I would like to say that this way of looking at history can be intellectually dishonest.

According to the historical view I have learned, there is no absolute of what is left or right. One political group is always to the left or to the right of another, depending on how much this group is revolutionary or reactionary. Thus, the bourgeois were revolutionaries at one time, but today they are no longer. But what happens when the Socialists come to power? Do not they themselves become reactionary, defenders of the status quo? According to everything they taught me, no. The revolution is permanent. My assessment is that at this point they are partly right: the revolution must be permanent.

Socialists can not take the risk of becoming exactly what they fought at the first place. In practice, however, this is not the case: the Socialists occupy the posts of the state and begin to defend their position and these positions more than anything else. That’s what I see in my country today. In practice, it is impossible to be revolutionary all the time, just as it is impossible to be relativistic in a consistent way. I have not yet met a person who, looking at the red light, said “but to me it’s green and all these other cars are just a narrative of patriarchal society.”

Politics is unfortunately, for the most part, simply a search for power. Even the most idealistic groups need the power to put their agendas into practice. And experience shows that once installed in power, many idealistic groups become pragmatic.

Socialism is not revolutionary. It is only a reaction against the real revolution that is capitalism defended by classical liberalism. Classical liberalism says: men are all equal, private property is inviolable, exchanges can only occur voluntarily and no one can be forced to work against their will. Marxism responds: men are not all the same (they are divided into classes), private property is relative (if it is in the interest of the collective I can take what was once yours) and you will work for our cause, whether or not you want to. In short, Marxism is a return to the Old Regime.

Communist Yugoslavia

Below is an excerpt from my book I Used to Be French: an Immature Autobiography. You can buy it on amazon here.

I was led into a large cell with an arching stone ceiling I would have called a dungeon except that it was harshly lit. There were about twenty-five men in the room, mostly in their late twenties. They greeted me loudly in their language. An older man who looked vaguely middle class because he wore a suit (without a tie) asked me in Italian where I was from. There were five or six blankets altogether. A tall, bony guy with the ravaged face of an operetta brigand requisitioned two and handed them to me. Then, we all lined up for whole-grain bread and soup. (Yes, whole-grain used to be the cheapest before it became fashionable, in the seventies.) The brigand pushed me to the head of the line. Then he showed me that you had to dunk the hard bread into the soup to soften it. After dinner, I had a long, civilized conversation with the old man, he speaking Italian and I, French. He told me that most of my cellmates were returning from Germany where they had gone to work without a proper Yugoslav exit visa, and that they were awaiting trial for that low-grade offense. “Why don’t they look more worried?”- I asked. (The mood was, in fact, downright merry.) He told me each would get a few months in the poker but that the cars they had bought in Germany with their earnings would be awaiting them when they got out. In fact, he said, the jail had a parking lot reserved for that usage. Real communism, communism as it existed, communism with a small “c,” was not simple!

As evening came, the inmates prepared for bed in their own rudimentary ways. There was tenseness when the brigand signaled for me to set down my two blankets next to him, on a raised wooden platform. I was old enough to doubt a free lunch existed. I perceived that I was the cutest thing in the joint, and the youngest! With no gracious way to escape, I did as he suggested. Tension turned into panic when he took my head into the crook of his arm. I withdrew brusquely. He delivered himself of a vociferous and loud speech that I guessed was at once re-assuring and reproachful. There was probably no ambiguity in his gesture. Yugoslavia was the beginning of the mysterious Orient, deep into Western Europe, with different customs. Later, I saw soldiers, and once, a pair of policemen, walking peaceably hand in hand. The brigand had just adopted me as a brother. He was no jail predator. For all I know, he had protected me from the real thing.

How Well Has Cuba Managed To Improve Health Outcomes? (part 2)

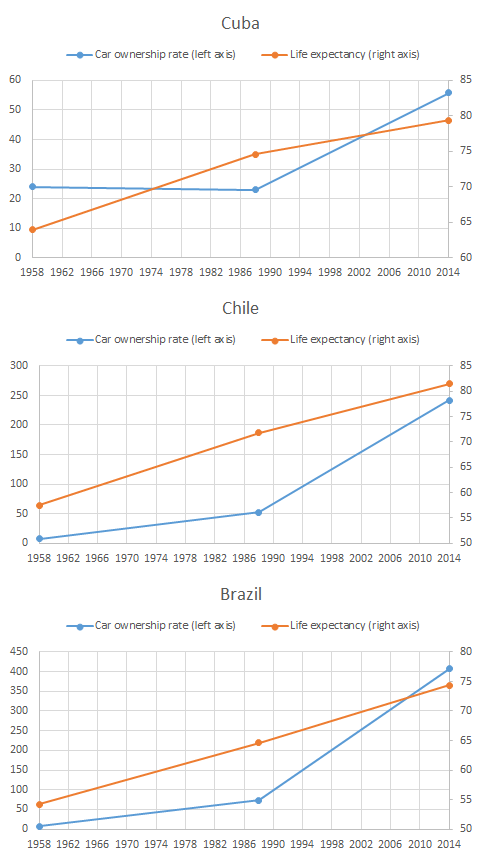

In a recent post, I pointed out that life expectancy in Cuba was high largely as a result of really low rates of car ownerships. Fewer cars, fewer road accidents, higher life expectancy. As I pointed out using a paper published in Demography, road fatalities reduced life expectancy by somewhere between 0.2 and 0.8 years in Brazil (a country with a car ownership rate of roughly 400 per 1,000 persons). Obviously, road fatalities have very little to do with health care. Praising high life expectancy in Cuba as the outcome Castrist healthcare is incorrect, since the culprit seems to be the fact that Cubans just don’t own cars (only 55 per 1,000). But that was a level argument – i.e. the level is off.

It was not a trend argument. The rapid increase in life expectancy is undeniable, so my argument about level won’t affect the claim that Cubans saw their life expectancy increase under Castro.

I say “wait just a second”.

Cuba is quite unique with regards to car ownership. In 1958, it had the second highest rate of car ownership of all Latin America. However, while the rate went up in all of Latin America between 1958 and 1988, it went down in Cuba. During that period, life expectancy went up in all countries while there were substantial increases in car ownership (which would, all things being equal, slow down life expectancy growth). Take Chile and Brazil as example. In these countries, the rate went up by 6.9% and 8.1% every year – these are fantastic rates of growth. During the same period, life expectancy increased 25% in Chile and 19% in Brazil compared with Cuba where the increase stood at 17%. In Cuba, the moderate decline in car ownership (-0.1% per annum) would have (very) modestly contributed to the increase of life expectancy. In the other countries, car ownership hindered the increase. (The data is also from the WHO section on Road Safety while the life expectancy data is from the World Bank Database)

This does not alter the trend of life expectancy in Cuba dramatically, but it does alter it in a manner that forces us, once more, to substract from Castro’s accomplishments. This increase would not have been the offspring of the master plan of the dictator, but rather an accidental side-effect springing from policies that depressed living standards so much that Cubans drove less and were less subjected to the risk of dying while driving. However, I am unsure as to whether or not Cubans would regard this as an “improvement”.

Below are the comparisons between Cuba, Chile and Brazil.

The other parts of How Well Has Cuba Managed To Improve Health Outcomes?

- Life Expectancy Changes, 1960 to 2014

- Car ownership trends playing in favor of Cuba, but not a praiseworthy outcome

- Of Refugeees and Life Expectancy

- Changes in infant mortality

- Life expectancy at age 60-64

- Effect of recomputations of life expectancy

- Changes in net nutrition

- The evolution of stature

- Qualitative evidence on water access, sanitation, electricity and underground healthcare

- Human development as positive liberty (or why HDI is not a basic needs measure)

Great quotes by Vladimir Lenin

Last week I posted some quotes by Joseph Stalin. I’m afraid too many people are still misguided by the myth that Lenin was a good leader whose plans were somehow distorted by Stalin. Nothing could be further from the truth. Joseph Stalin had a great teacher, Vladimir Lenin, and brought the plans of his teacher to perfection. Here are some quotes by Lenin, so that we can learn more about international Marxism. Notice that he sounded very reasonable and pacific before 1917, and not so much so when revolution actually came.

On terror:

The Congress decisively rejects terrorism, i.e., the system of individual political assassinations, as being a method of political struggle which is most inexpedient at the present time, diverting the best forces from the urgent and imperatively necessary work of organisation and agitation, destroying contact between the revolutionaries and the masses of the revolutionary classes of the population, and spreading both among the revolutionaries themselves and the population in general utterly distorted ideas of the aims and methods of struggle against the autocracy.

Lenin, Vladimir Ilich (July–August) [1903], “Second Congress of the RSDLP: Drafts of Minor Resolutions”, Collected Works, 6, Marxists.

It is necessary — secretly and urgently to prepare the terror. And on Tuesday we will decide whether it will be through SNK or otherwise.

Memorandum to Nikolay Nikolayevich Krestinsky (3 or 4 September 1918) while recovering from an assassination attempt by Socialist-Revolutionary Fanni Kaplan on 30 August 1918; published in The Mitrokhin Archive: The KGB in Europe and the West (1999) Christopher Andrew and Vasili Mitrokhin, p. 34.

On democracy:

Whoever wants to reach socialism by any other path than that of political democracy will inevitably arrive at conclusions that are absurd and reactionary both in the economic and the political sense.

Lenin, Vladimir Ilich (Summer) [1905], “Two Tactics of Social Democracy in the Democratic Revolution”, Collected Works, 9, Marxists, p. 29.

You cannot do anything without rousing the masses to action. A plenary meeting of the Soviet must be called to decide on mass searches in Petrograd and the goods stations. To carry out these searches, each factory and company must form contingents, not on a voluntary basis: it must be the duty of everyone to take part in these searches under the threat of being deprived of his bread card. We can’t expect to get anywhere unless we resort to terrorism: speculators must be shot on the spot. Moreover, bandits must be dealt with just as resolutely: they must be shot on the spot.

“Meeting of the Presidium of the Petrograd Soviet With Delegates From the Food Supply Organisations” (27 January 1918) Collected Works, Vol. 26, p. 501.

On individual liberty:

Everyone is free to write and say whatever he likes, without any restrictions. But every voluntary association (including the party) is also free to expel members who use the name of the party to advocate anti-party views. Freedom of speech and the press must be complete. But then freedom of association must be complete too.

Lenin, Vladimir Ilich (13 November 1905), “Party Organisation and Party Literature”, Novaya Zhizn (Marxists) (12).

We set ourselves the ultimate aim of abolishing the state, i.e., all organized and systematic violence, all use of violence against people in general. We do not expect the advent of a system of society in which the principle of subordination of the minority to the majority will not be observed.

In striving for socialism, however, we are convinced that it will develop into communism and, therefore, that the need for violence against people in general, for the subordination of one man to another, and of one section of the population to another, will vanish altogether since people will become accustomed to observing the elementary conditions of social life without violence and without subordination.

Lenin, Vladimir Ilich, The State and Revolution, Ch. 4: “Supplementary Explanations by Engels”

On violence:

No Bolshevik, no Communist, no intelligent socialist has ever entertained the idea of violence against the middle peasants. All socialists have always spoken of agreement with them and of their gradual and voluntary transition to socialism.

“Reply to a Peasant’s Question” (15 February 1919); Collected Works, Vol. 36, p. 501.

When violence is exercised by the working people, by the mass of exploited against the exploiters — then we are for it!

“Report on the Activities of the Council of People’s Commissars” (24 January 1918); Collected Works, Vol. 26, pp. 459-61.

Great quotes by Joseph Stalin

Sometimes I like to read quotes by famous intellectuals and leaders. I believe it is a great way to learn one thing or two about several subjects, and specially the thought of said people. I suddenly became curious about Joseph Stalin, and to my surprise he was at times a very reasonable (albeit terribly evil) person. Here are some quotes by Joseph Stalin I subjectively find interesting:

On Social Democracy:

Social democracy is objectively the moderate wing of fascism…. These organisations (ie Fascism and social democracy) are not antipodes, they are twins.

Joseph Stalin, “Concerning the International Situation,” Works, Vol. 6, January-November, 1924, pp. 293-314.

On Anarchism:

We are not the kind of people who, when the word “anarchism” is mentioned, turn away contemptuously and say with a supercilious wave of the hand: “Why waste time on that, it’s not worth talking about!” We think that such cheap “criticism” is undignified and useless.

(…)

We believe that the Anarchists are real enemies of Marxism. Accordingly, we also hold that a real struggle must be waged against real enemies.

Anarchism or Socialism (1906)

On differences within the communist movement:

We think that a powerful and vigorous movement is impossible without differences — “true conformity” is possible only in the cemetery.

Stalin’s article “Our purposes” Pravda #1, (22 January 1912)

He did make a lot of people conform to his ideas.

On diplomacy:

A sincere diplomat is like dry water or wooden iron.

Speech “The Elections in St. Petersburg” (January 1913)

On the press:

The press must grow day in and day out — it is our Party’s sharpest and most powerful weapon.

Speech at The Twelfth Congress of the R.C.P.(B.) (19 April 1923)

On elections:

I consider it completely unimportant who in the party will vote, or how; but what is extraordinarily important is this—who will count the votes, and how.

Said in 1923, as quoted in The Memoirs of Stalin’s Former Secretary (1992) by Boris Bazhanov [Saint Petersburg]

On education:

Education is a weapon whose effects depend on who holds it in his hands and at whom it is aimed.

Interview with H. G. Wells (September 1937)

On Hitler:

So the bastard’s dead? Too bad we didn’t capture him alive!

Said in April 1945 — On hearing of Hitler’s suicide, as quoted in The Memoirs of Georgy Zhukov

On his role as a leader at the USSR:

Do you remember the tsar? Well, I‘m like a tsar.

To his mother in the 1930s as quoted in Young Stalin (2007) by Simon Sebag Montefiore

To finish, a comment by George Orwell about Stalin, and above that, about people in the West who failed to see what the USSR actually was:

I would not condemn Stalin and his associates merely for their barbaric and undemocratic methods. It is quite possible that, even with the best intentions, they could not have acted otherwise under the conditions prevailing there.

But on the other hand it was of the utmost importance to me that people in western Europe should see the Soviet regime for what it really was. Since 1930 I had seen little evidence that the USSR was progressing towards anything that one could truly call Socialism. On the contrary, I was struck by clear signs of its transformation into a hierarchical society, in which the rulers have no more reason to give up their power than any other ruling class. Moreover, the workers and intelligentsia in a country like England cannot understand that the USSR of today is altogether different from what it was in 1917. It is partly that they do not want to understand (i.e. they want to believe that, somewhere, a really Socialist country does actually exist), and partly that, being accustomed to comparative freedom and moderation in public life, totalitarianism is completely incomprehensible to them.

George Orwell, in the original preface to Animal Farm; as published in George Orwell : Some Materials for a Bibliography (1953) by Ian R. Willison

The Myth of Common Property

An Observation by L.A. Repucci

It has been proposed that there exists a state in which property — whether defined in the physical sense such as objects, products, buildings, roads, etc, or financial instruments such as monetary instruments, corporate title, or deed to land ownership — may be owned or possessed in common; that is to say, that property may be possessed of multiple rightful claimants simultaneously. This suggestion, when examined rationally and exhaustively, is untenable from the perspective of any logical school of economic, social, and indeed physical school of thought, and balks at simple scrutiny.

In law, Property may be defined as the tangible product of enterprise and resources, or the gain of capital wealth which it may create. To ‘hold’ Property, a Party, or private, sentient entity, must have rightful claim to it and be capable of using it freely as they see fit, in keeping with natural law.

Natural resources, including land, are said to be owned either jurisdictionally by State, privately by party, or in common to the natural world. If property may be legally defined only as a product, then natural resources may be excluded from all laws pertaining to legal property. If property also may be further defined by the ability of it’s owner to use it as they see fit, in keeping with Ius Naturale, then any property claimed jurisdictionally by the State and said to be held in common amongst the citizenry must meet the article of usage to be legally owned. Consider Hardin’s tragedy of the commons as an argument for the conservation of private property over a state of nature, rather than an appeal to the economic law of scarcity or an appeal to the second law of thermodynamics ,

In Physics: Property may be defined as either an observable state of physical being. The universe of Einstein, Kepler, and Newton rests soundly on the tenet that physical bodies cannot occupy multiple physical locations simultaneously. The laws that govern the macro-physical world do not operate in the same way on the quantum level. At that comparatively tiny level, the rules of our known universe break down, and matter may exhibit the observed property of being at multiple locations simultaneously — bully and chalk 1 point for common property on the theoretically-quantum scale.

Currency: The attempt to simultaneously possess and use currency as defined above would result in praxeologic market-hilarity in the best case, and imprisonment or physical injury in the worst. Observe: Two friends in common possession of 1$ walk into a corner shop to buy a pack of chewing gum, which costs 1$. They each place a pack on the counter, and present the cashier with their single dollar bill. “It’s both of ours! We earned it in business together!” they beam as the cashier calls the cops and racks a shotgun under the register…

The two friends above may not use the paper currency simultaneously — while the concept of a dollar representing two, exclusively owned fifty-percent equity shares may be widely and innately understood — the single bill is represented in specie among the parties would still be 2 pairs of quarters. While they could pool their resources and ‘both’ purchase a single pack of gum, they would continue to own a 50% equity share in the pack — resulting in a division yet again of title equally between the dozen-or-so sticks of gum contained therein. This reduction and division of ownership can proceed ad quantum.

This simple reason is applicable within and demonstrated by current and universal economic realities, including all claims of joint title, common property law, jurisdictional issues, corporate law, and financial liability. A joint bank account is simply the sum of the parties’ individual interest in that account — claims to hold legal property in common are bunk.

The human condition is marked by the sovereignty, independence and isolation of one’s own thought. Praxeological thought-experiments like John Searle’s Chinese Room Argument and Alan Turing’s Test would not be possible to pose in a human reality that was other than a state of individual mental separation. As we are alone in our thoughts, our experience of reality can only be communicated to one another. It is therefore not possible to ever ‘share’ an experience with any other sentient being, because it is not possible to perceive reality as another person…even if the technology should develop such that multiple individuals can network and share the information within their minds, that information must still filter through another individual consciousness in order to be experienced simultaneously. The physical separation of two minds is reinforced by the rationally-necessary separation of distinct individuals. There may exist a potential hive-mind collectivist state, but it would require such a radical change to that which constitutes the human condition, that it would violate the tenets of what it is to be human.

In conclusion, logically, the most plausible circumstance in which property could exist in common would be on the quantum level within a hive-minded non-human collective, and the laws that govern men are and should be an accurate extension of the laws that govern nature — not through Social Darwinism, but rather anthropology. Humans, as an adaptation, work interdependently to thrive, which often includes the voluntary sharing and trading of resources and property…none of which are held in common.

Ad Quantum,

L.A. Repucci

Around the Web

- Missing from President’s Day: The People They Enslaved

- The Left Still Harbors a Soft Spot For Communism from Cathy Young at Reason

- Tyler Cowen on practical gradualism vs. moral absolutism, for immigration and revolution; see also Dr Delacroix’s very relevant “If Mexicans and Americans Could Cross the Border Freely” article [pdf] in the Independent Review

- Writing in the Wall Street Journal, James Freeman reviews the results of Obama’s stimulus package five years on

- Theologian and philosopher Eric Hall on Confusing Confucianism with Collectivism

“Cybernetics in the Service of Communism”

In October, 1961, just in time for the opening of the XXII Party Congress, a group of Soviet mathematicians, computer specialists, economists, linguists, and other scientists interested in mathematical model and computer simulation published a collection of papers called “Cybernetics in the Service of Communism”. In that collection they offered a wide variety of applications of computers to various problems in science and in the national economy.

From this video interview of MIT Lecturer (and historian) Vyacheslav Gerovitch conducted by the website Serious Science. The interview is only 15 minutes long.

Is President Obama the culmination of American Marxism?

I recently tried my hand at prodding Jacques to blog more often about Marxism and Marxist thought. As an immigrant from a country with a strong Marxist tradition and – more importantly – with his educational background (Stanford’s sociology department in the late 60s/early 70s; arguably the time period with the most sophisticated understanding of Marxist thought ever), I think he provides readers with a nuanced and sharply critical glance into Marxism, something that is very tough to do. Alas:

Brandon: Thanks for the suggestion and for the incense. However, the charm of blogging has much to do for me with following whatever my inspiration whispers at any one time. Once in a while, it lands on Marxism, not often. When it does, it’s often in the context of conversations in French with French speakers. (You may have noticed something on my blog called, “Le dernier Communiste.” )

To the extent that I am impelled to do the needful rather than the natural, I direct my steps to whatever I think I do well and that is also in demand. In general, I am not sure waking up Marx for the benefit of young Americans is useful or much in demand. Almost no one in America calls himself a Marxist anymore . (There were many when I was young.) The people who would have been Marxists in 1974 call themselves “environmentalists” today. Aside from this, I suspect

that the Obama administration is the result of wet dreams by Marxists of my generation but I don’t know how to talk about it. It’s just my sense of smell telling me.I make a mental note of your expressed demand for Marxist critiques. In the meantime, feel free to pillage whatever you find on the subject in my blogs.

Oh, I’ve pillaged. His knowledge of Marxism is too important for me to ignore it. You can find Jacques’s thoughts on Marxism here. Jacques is also working on his memoirs, and you can find excerpts of those here (it’s also located on the top right side of the blog’s navigation bar).

As far as President Obama being the culmination of American Marxism, I think Jacques is woefully wrong. However, I also think Jacques’s assessment of Marxism in the US today (it’s irrelevant) is spot on. There is a recent, well-written essay in Dissent by a political scientist at Columbia arguing that the Obama administration is simply kowtowing to a neoliberal (and, by extension, racist) agenda, and this, I think, suggests that my suspicions are correct.

Shopping in communism versus capitalism

In a narrative portion of his latest (and characteristically riveting) novel the author has written the following sentence that prompts me to wag my finger at him a bit. “Now it was a Western-style shopping mall stuffed with all the useless trinkets capitalism had to offer…” Daniel Silva, The English Girl (2013). The sentence reveals something very important about capitalism as well as Silva’s apparent failure to understand it.

Silva was contrasting the Soviet style, drab, grey shopping center with the more recent type that have been springing up in Russia and the former Soviet bloc. Yet instead of showing appreciation for the mall with its great variety of trinkets, which include both what he can consider useless and the useful kind, he appears to show disdain for it.

It is precisely the fact that such malls include thousands of trinkets, some useful to some, some not, that makes capitalism so benevolent. Unlike the Soviet Union and its satellites, where only what the leadership deemed to be useful got featured in shopping malls (such as they were), in Western-style malls millions of different individual and family preferences are on display and for sale, aiming to satisfy the huge variety of tastes and preferences.

I recall many moons ago there was a fuss about the popularity of the Pet Rock! It was — may still be — a trinket sold as a novelty item. I remember defending it from its disdainful, snooty critics, arguing that there may well be a few people for whom it would be suitable gift.

Say your grandfather worked in a mine or quarry and now on his 80th birthday you want to get him something not quite useful but meaningful! He has everything useful already, so you pick the Pet Rock for him. It would make a nifty memento! Might even bring tears to his eyes.

For millions of others it would indeed be a “useless trinket” but not for old granddad. And for every other item that author Silva may consider useless, there will be someone who finds it touching!

That is precisely what individualism implies. Something Marxists cannot appreciate since for them only what advances the revolution counts as useful. Individuals as such, with their idiosyncrasies, do not count for anything! And capitalism rejects this misanthropic doctrine, which is why the enormous variety of goods and services is part of it while under socialism and communism only what is proper for the revolution makes sense to produce!

I wish Mr. Silva had indicated some of this as he derided those Western-style shopping malls. Even if he cannot find something useful for himself in them, he can at least appreciate them as contemporary museums of possibilities.

Classical Liberals Who Weren’t Right About Everything

Many classical liberals and their ideas have been maligned by their interpreters. We must set the record straight. Professor Ross Emmett, in “What’s Right with Malthus,” from The Freeman, champions the cause of Thomas Robert Malthus, who, contrary to what one might think after encountering Malthus’ followers and critics,

argued that private property rights, free markets, and…marriage were essential features of an advanced civilization.

Some disciples of Malthus took his erroneous population theory as evidence of the need for eugenics, population control, and environmental “regulation.” They ignored Malthus’ arguments favoring institutions more capable of (and more compassionate in) achieving their desired ends; institutions that first came about not by design, but by convention. The eugenicists Francis Galton and Julian Huxley (both related to Darwin), and eco-catastrophist Paul Ehrlich come to mind.

But there were also critics, who, preferring utopian visions of the perfectibility of mankind, denounced Malthus’ pessimistic views. Anarchists William Godwin and Pierre-Joseph Proudhon are most notable in this regard. Godwin and Malthus had exchanged criticisms (noted by Emmett) in some of their essays. Malthus attacked Godwin’s utopianism. Godwin assailed Malthus’ assumption of arithmetical increase in agricultural output, as compared to geometrical increase of population. And Proudhon targeted the overzealous Malthusians of his day, citing as grievances the former’s antagonism toward the lower classes. While neither Godwin nor Proudhon did terrible injustice to Malthus himself, they unintentionally contributed to the myth that the worst variety of population catastrophists were the most orthodox.

Notice the themes that Professor Emmett brings to our attention. First, that even in their controversial and disputable contributions, great theorists illuminate the path for later philosophers. Second, that human institutions can mitigate human nature’s undesirable effects.

In light of these, consider two other social theorists whose ideas have been abused by overenthusiastic students and overreactive peers alike: Herbert Spencer (insightful Malthus adherent), and the aforementioned Mr. Proudhon (noteworthy Malthus critic).

Leading “social Darwinist” (a pejorative used to link eugenics and capitalism), Herbert Spencer (considered a conservative anarchist by Georgi Plekhanov) was, like Darwin, influenced by Malthus’ idea that the fittest tend to survive overpopulation-induced catastrophes. He is known for having coined “survival of the fittest,” a term later used by Darwin in the fifth edition of On the Origin of Species (1859). Spencer originally used it to convey Darwin’s concept of natural selection, and drew parallels between biological evolution through natural selection and social evolution through market competition. But he never implied that they were identical or that marketplace competition was necessarily an outgrowth of natural selection.

If anything, it should be thought of as an alternative to natural selection. Humans, to survive as a species, might practice natural selection as a matter of biological fact. And without the ability to reason this might eventually lead to a Hobbesian jungle. But since man is rational, natural selection’s role in social evolution is significantly lessened. Society arises from the natural order of things. There is no need for the Commonwealth or the General Will to step in and provide it.

Friedrich Engels saw things differently when he wrote in the introduction to his Dialectics of Nature (1872/1883):

Darwin did not know what a bitter satire he wrote on mankind…when he showed that free competition…is the normal state of the animal kingdom. Only…production and distribution…carried on in a planned way, can lift mankind above the rest of the animal world…

Competition exists in both the natural world and free markets, so the connection between natural selection and marketplace competition, though spurious, seems all too obvious for critics of one or the other. They wrongfully project the cold, deterministic properties of nature onto economic freedom. But marketplace competition is an outgrowth of the ability to reason, not base survival instincts. The will to survive is certainly a factor of social progress, but taken on its own would tend toward more similarities with nature, such that the life of man would be “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.” Man has the faculties to escape the jungle, to leave the animal kingdom, to better his life without worsening others’.

Communist anarchist Pyotr Kropotkin (influenced by Godwin) juxtaposed social Darwinism, evolution requiring competition, with his own take, evolution requiring cooperation, in his book Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution (1902). In so doing, he disagreed with Engels on Darwin, by describing how natural selection depended at least as much upon cooperation as it did biological competition. But unfortunately he conformed to Engels on the false dichotomy between rational competition (free markets) and cooperation (mutual aid).

Our second subject, Pierre-Joseph Proudhon was a mutualist, an anarchist and a socialist. Yet some of his ideas are more in line with libertarianism than with contemporary socialism. They were often based on a fairly consistent concept of natural rights, but understood in light of fallacious economic principles, especially the labor theory of value (held by Locke, Smith, Ricardo, and Marx).

But utility-based theories are in vogue among today’s classical liberals and much of Proudhon’s economics has been rightly tossed aside. But his theory of spontaneous order and support for free markets should not be so readily discarded. Leave that to conservatives fearful of anything tainted by the socialist label, and to leftists whose only alternative would be to admit that the labor theory is passé.

Proudhon (General Idea of the Revolution in the Nineteenth Century, 1851) was also opposed to Hobbes’ and Rousseau’s social contract theories, having his own:

What really is the Social Contract? An agreement of the citizen with the government? No…The social contract is an agreement of man with man…from which must result what we call society…Commerce…the act by which man and man declare themselves essentially producers, and abdicate all pretension to govern each other.

Organic institutions, neither designed nor imposed!

It seems there’s much knowledge and inspiration to be gained by examining the forgotten words of discredited intellectuals. Warts and all.