- Argentine Nazi finds are fakes Glüsing & Wiegrefe, Spiegel

- China’s looming class struggle Joel Kotkin, Quillette

- The real costs of the war in Afghanistan Adam Wunische, New Republic

- Progressive purity tests and Supreme Court wish lists Damon Root, Reason

Nightcap

- Ottoman cosmopolitanism Ussama Makdisi, Aeon

- American racism Coleman Hughes, City Journal

- WTO arrogance John Quiggan, the Conversation

- Chinese Antarctica David Fishman, Lawfare

Nightcap

- How American anthropology redefined humanity Louis Menand, New Yorker

- China’s new Great Wall rises in the heart of Europe Katsuji Nakazawa, Asian Nikkei Review

- Chile: neoliberalism’s poster boy falls from grace Branko Milanovic, globalinequality

- Turkey rejects German-NATO plan, cozies up to Russia Laura Kayali, Politico

Nightcap

- Second-hand: the new global garage sale Susan Blumberg-Kason, Asian Review of Books

- Learning to love America Jacques Delacroix, NOL

- “Why I don’t trust the police” Michelangelo Landgrave, NOL

- Chicago cops Paul Buhle, Counterpunch

Nightcap

- John Mbiti (Kenyan Anglican) is dead Richard Sandomir, New York Times

- The long history of eco-pessimism Desrochers & Szurmak, spiked!

- An early case for reparations Eric Herschthal, New Republic

- What the 1956 Uprising says about Hungary today KB Vlahos, American Conservative

Nightcap

- Who betrayed Syria’s Kurds? Amberin Zaman, Al-Monitor

- How the Physiocrats confronted France’s empire (Smithian-Misesian-Hayekian federation) Pernille Røge, Age of Revolutions

- Strange respect for central banks Scott Sumner, MoneyIllusion

- This is just the beginning of Brexit Tom McTague, the Atlantic

Nightcap

- Making Canada great for the first time Scott Sumner, EconLog

- Detoxifying Brexit Chris Dillow, Stumbling & Mumbling

- What’s driving protests around the world? Tyler Cowen, Bloomberg

- “There’s no telling what’s next” Conor Friedersdorf, the Atlantic

The North Syria Debacle as Seen by One Trump Voter

As I write (10/22/19) the pause or cease-fire in Northern Syria is more or less holding. No one has a clear idea of what will follow it. We will know today or tomorrow, in all likelihood.

On October 12th 2019, Pres. Trump suddenly removed a handful of American forces in northern Syria that had served as a tripwire against invasion. The handful also had the capacity to call in air strikes, a reasonable form of dissuasion.

Within hours began an invasion of Kurdish areas of Syria by the second largest army in Europe, and the third in the Middle East. Ethnic cleansing was its main express purpose. Pres Erdogan of Turkey vowed to empty a strip of territory along its northern border to settle in what he described as Syrian (Arab) refugees. This means expelling under threat of force towns, villages, and houses that had been occupied by Kurds from living memory and longer. This means installing on that strip of territories unrelated people with no history there, no housing, no services, and no way to make a living. Erdogan’s plan is to secure his southern border by installing there a permanent giant refugee camp.

Mr Trump declared that he had taken this drastic measure in fulfillment of his (three-year old) campaign promise to remove troops from the region. To my knowledge, he did not explain why it was necessary to remove this tiny number of American military personnel at that very moment, or in such haste.

Myself, most Democrats, and a large number of Republican office holders object strongly to the decision. Most important for me is the simplistic idea that

Davies’ “Extreme Economies” – Part 2: Failure

In the previous part of this three-part review, I looked at Davies’ first subsection (“Survival”) where he ventured to some of the most secluded and extreme places of the world – a maximum security prison, a refugee camp, a tsunami disaster – and found thriving markets. Not in that pejorative and predatory way markets are usually denounced by their opponents, but in a cooperative, resilient and fascinating way.

In this second part, subtitled “The Economics of Lost Potential”, Davies brings us on a journey of extreme places where markets did not deliver this desirable escape from exceptionally restrictive circumstances.

There might be many reasons for why Extreme Economies has become a widely read and praised book. Beyond the vivid characters and fascinating environments described by Davies, this swinging between opposing perspectives is certainly one. Whether your priors are to oppose markets or to favour them, there is something here for you. Davies isn’t “judgy” or “preachy” and the story comes off as more balanced because of it.

If the previous section showed how markets flourish and solve problems even under the most strained conditions, this section shows how they don’t.

Darien, Panama

We first venture to the Darien Gap, the 160-kilometre dense rainforest that separates the northern and southern sections of the Pan-American Highway – an otherwise unbroken road from Alaska to the southern tip of Argentina.

To a student of financial history, “Darien” brings up William Paterson’s miserable Company of Scotland scheme in the 1690s; trying to make Scotland great (again?), the scheme raised a large share of scarce Scottish capital and spectacularly squandered it on trying to build a colony halfway around the world. In the first chapter of subsection ‘Failure’, Davies skilfully recounts the Darien Disaster, “Scotland’s greatest economic catastrophe” (p. 114).

Judging from Davies’ ventures into the jungle bordering Panama and Colombia, it wouldn’t be a far cry to call the present state of affairs a similar economic catastrophe. Rather than failed colonies, the failed potential of Darien lies elsewhere: its environmental challenges coupled with the trade and markets that failed to emerge despite readily available mutual gains for trade.

A stunning landscape of mile after mile filled with rainforests and rivers and the occasional lush farmland, the people of the Gap make a living through extracting what the land provides. If you’re deep into environmentalism, you might even say unsustainably so. Davies’ point is to illustrate a more well-known economic problem: when unowned or communally owned resources suffer from the tragedy of the commons – the tendency is for such resources to be overexploited and ultimately destroyed.

Whether through logging companies exceeding their quotas or locals chopping trees out of desperation to survive, the story in Darien is altogether conventional. At the edge of the Gap, “the people of Yaviza do what they can. [T]he environment is an asset, and for many people living in Yaviza getting by is only possible by chipping a bit off a selling it” (p. 120).

What’s striking here is that in times of need (as Davies himself showed in the chapter on Aceh) that’s exactly what we want assets to do! We can show this in down-to-earth, real-world examples like Acehnese women drawing on their jewellery as emergency savings, or in formal economic models such as the C-CAPM, the Consumption Capital Asset Pricing Model, familiar to every business and finance student.

On a much cruder level: if the mere survival of some of the poorest people on earth depend on chopping down precious trees – well, precious to far-away Westerners, anyway – accusing those people of destroying our shared environment is mind-blowingly daft. To rationalise that equation, you have to put a very large value on turtles and trees, and a very small value on human life.

Elinor Ostrom, whose Nobel Prize in economics was awarded to her work on common pool resources, emphasised three ways to solve tragedies of the commons: clear boundaries (i.e. individual property rights); regular communal meetings such that members can voice opinions and amicably resolve conflicts; a stable population so that reputation matters and we can socially police deviant behaviour (p. 125).

The Darien Gap has none of those. Property rights are routinely ignored; the forest includes many different populations (indigenous tribes, farmers, ex-FARC fugitives, illegal immigrants); and those populations fluctuate a lot, meaning that most interactions are one-shot games where reputation becomes useless. End result: extensive, illegal, unsustainable logging mixed with armed strangers.

What I can’t quite wrap my head around is that almost all (market and non-market) interactions that all of us have daily are with strangers: the barista, the people we walk past on the street, the new client you just met or the customer support agent you just talked to. All of them are strangers. A large share of interactions with other humans in the last few centuries of human societies have been one-offs, yet very few of them have spiral into the lawlessness that Davies describes in Darien. Be it the Leviathan, secure property rights, the doux commerce thesis or some wider institutional or cultural reason, but the failure of Darien to establish well-functioning formal and informal markets of the kind we saw in the book’s first part are intriguing.

While a fascinating chapter, it might also be Davies’ worst chapter, factually speaking. He claims, mistakenly, that “globally, deforestation continues apace with 2016 the worst year on record for tree loss”. On the contrary, we’re approaching global zero net deforestation. More specifically, Davies claims that Colombia and Panama are particularly at risk here, with rates deforestation “increased sharply”. A quick look through UN’s Global Forest Resource Assessment report (latest figures from 2015), these two countries are indeed chopping down their forests – but by less than any other time period on record. Moreover, the Colombian net deforestation rate of 0.05% per year is easily exceeded by a number of countries; not even Panama’s dismal 0.3%/year (worse than the Brazilian Amazon) is particularly high in a global or historical perspective.

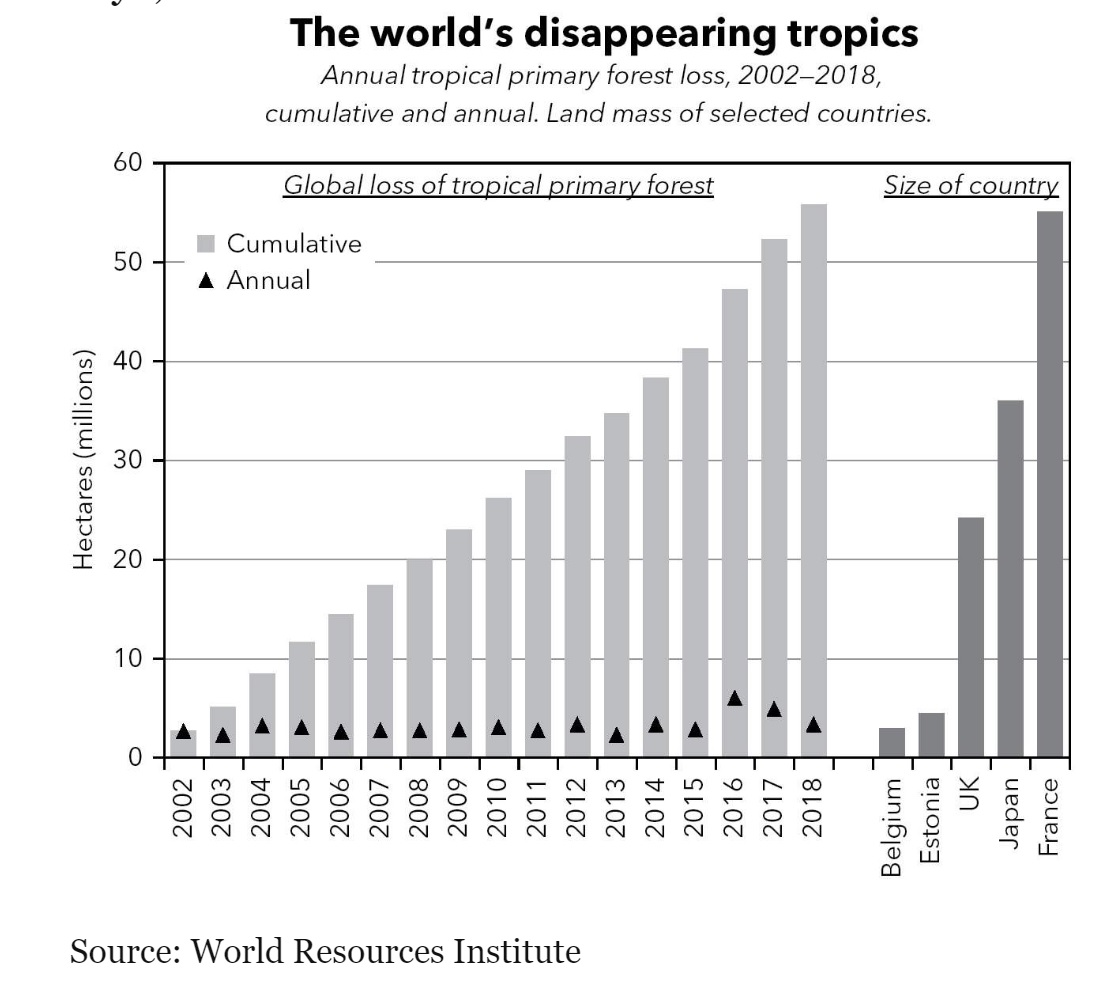

To make matters worse, the figure on p. 158 titled “The World’s Disappearing Tropics” might win an award for the most misleading graph of the year: by making the bars cumulative and downplaying the annual deforestation, it suggests that the forests are rapidly disappearing. The only comparison to relevant numbers (remember, Rosling teaches us to Always Be Comparing Our Numbers) is the tired “football pitches”. That’s hugely misleading. A vast amount of football pitches cleared in the Amazon this year still only amounted to 0.2% of the Brazilian Amazon; in other words, Brazilians could keep chopping down trees for a few good decades without making much of a dent to that vast rainforest.

Moreover, the only reference point we’re given is that over a period of almost twenty years, an area the size of France has been deforested – but that’s equivalent to no more than one-tenth of only the Amazon forest, and the tropics have many more forested areas than that. The graph aims to intimidate us with ever-rising bars signalling the loss of forests; with some proper numbers and further examination it doesn’t seem very bad at all. On the contrary, locals (and yes, international logging companies) use the assets that nature has endowed them with – what’s so wrong with that?

Finally, the “missing market” that Davies observes in the Gap involves countless of illegal immigrants from around the world that trek through the jungles in search of a better life in the U.S. We have cash-rich Indians, willing to pay people to guide them through unknown and dangerous terrain, and local tribes and farmers and ex-FARC members with such knowledge looking for income; setting up a trade between them ought to be elementary.

Instead, it’s not: “in this place of flux,” writes Davies, “reputation does not matter, interactions are one-offs” (p. 137). Overturning the market quip that “trading is cheaper than raiding”, in the Darien Gap raiding is cheaper than trading. One might of course object that the failures of rich countries to offer more liberal immigration rules for people willing to go this far to get there illegally is hardly a market failure – but a failure of government regulation and incompetent bureaucracies.

Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC)

A 12-million people city sprawled on the banks of the Congo river, so unknown to Westerners that most of us couldn’t place it on a map. Democratic Republic of the Congo, the country with more people in extreme poverty than any other, is frequently described as “rich”. Or, with Davies’ euphemism “unrivalled potential” (p. 143).

Congo, the argument goes, has “diamonds, tin and other rare metals, the world’s second-largest rainforest and a river whose flow is second only to the Amazon. [it] shares a time zone with Paris [and the] population is young and growing”. It is one of the poorest countries but “should be one of the richest” (p. 143).

No, no and no. Before any other consideration of the remarkable day-to-day trading and corruption that Davies’ interview subjects describe, this mistaken idea about wealth must be straightened out. Wealth isn’t what could be if this or that major obstacle wasn’t in the way (Am I secretly a great singer, if I could only overcome the pesky fact that I have a voice unsuited for singing and lack practice?). This is almost tautological; what we mean by a country being poor is that it cannot overcome obstacles to wealth.

All wealth has to be created; humanity’s default position is extreme poverty.

And natural resources do not equate to wealth – there is even more support suggesting the opposite – in which case Japan and Singapore ought to be poor and Venezuela and DRC rich. My own sassy musings are still largely correct:

As Mises taught us half a century ago – and Julian Simon more recently – wealth (or even ‘goods’ or ‘commodities’ or ‘services’) are not the physical existence of those objects somewhere in the ground, but the satisfaction and valuation derived by the human mind. The object itself is only a means to whatever end the actor has in mind. Therefore, a “resource” is not the physical oil in the ground or the tons of iron ore in the Australian outback, but the ability of Human Imagination and Ingenuity to use those for his or her goals. After all, before humans learned to harnish the beautiful power of oil into heat, combustion engines and industrial production, it was nothing but a slimy, goe-y liquid in the ground, annoying our farmers. Nothing about its physical appearance changed over the centuries, but the mental abilities and industrial knowledge of human beings to use it for our purposes did.

Still, “modern Kinshasa is a disaster everyone should know about” (p. 172). No country has done worse in terms of GDP/capita since the 1960s. And we don’t have to go far to figure out at least part of the reason: the first rule of Kinshasa, says one of Davies’ interviewees, is corruption (p. 145). Everyone “steals a little for themselves as the funds pass through their hands, and if you pay in at the bottom of the pyramid there are hundreds of low-level tax officials competing to claim your cash.” (p. 185). Mobutu, the country’s long-time dictator, apparently said “if you want to steal, steal a little in a nice way” (p. 159).

Whether small stallholders at gigantic market or supermarket-owning tycoons, workers or university professors, pop-up sellers or police officers, everyone in Kinshasa uses every opportunity they can to extract a little rent for themselves – out of desperation more than malice. And everyone hates it: “The Kinoise”, writes Davies, “understand that these things should not happen, but recognize that their city’s economy demands a more flexible moral code.” (p. 168).

Interestingly enough, DMC is not a country whose state capacity is insufficient; it’s not a “failed state”, an “absent or passive” government whose cities are filled with “decaying official buildings and unfilled civil-service positions.” (p. 148). On the contrary:

The government thrives, with boulevards lined with the offices of countless ministries thronged by thousands of functionaries at knocking-off time. The Congolese state is active but parasitic, a corruption superstructure that often works directly against the interests of its people.

Poorly-paid police officers set up arbitrary roadblocks and extract bribes. Teachers demand a little something before allowing their pupils to pass. Restaurant owners serve their best food to their civil service regulators, free of charge, to even stay in business. Consequently, despite an incredibly resilient and innovative populace, “these innovative strategies are ultimately economic distortion reflecting time spent inventing ways to avoid tax collectors, rather than driving passengers or selling to customers” (p. 162).

But, like the ingenious monetary system of Louisiana prisons, the most fascinating aspect of Kinshasa’s economy is its use of money. Arbitrage traders head across the river to Brazaville in neighbouring Republic of the Congo equipped with dollars which they swap for CFA – the currency of six central African countries, successfully pegged to the euro. With ‘cefa’ they buy goods at Brazaville prices, goods they bring back over the river and undercut exorbitant Kinshasa prices. Selling in volatile and unstable Congolese francs carries risk, so Kinshasa’s streets are littered with currency traders offering dollars – at bid-ask spreads of less than 2%, comparing favourably with well-established Western currency markets. Before most transactions, Kinoise stop by an exchange trader sitting outside restaurants or malls, to acquire some Congolese francs with which to pay. Almost, almost dollarisation.

In Kinshasa, people rely on illegal trading as a safety net when personal disaster strikes or the state’s required bribes become too extortionary. Davies’ point is a convincing one, that “a town, city or country can get stuck in a rut and stay there” (p. 174).

Judging from his venture into Kinshasa, it’s difficult to blame markets for that. I don’t believe I’m invoking a No True Scotsman fallacies by saying that a market whose participants spent half their time avoiding public officials and the other half bribing them to avoid arbitrarily made-up rules, is pretty far from a free market.

Believing the opposite is also silly – that markets and mutual gains from trade can overcome any obstacles placed before them. Governments, culture or institutions have power to completely eradicate the beneficial outcomes of markets – Kinshasa’s extreme poverty attests to that.

Glasgow, the last part of ‘Failure’, is discussed in a separate post.

Nightcap

- The Great Firewall of China, as cyber-sovereignty John Lanchester, London Review of Books

- The lost art of exiting a war Adam Wunische, War on the Rocks

- The Eastern Jesus Ian Johnson, New York Review of Books

- China’s first permanent president Johnathan Chatwin, Asian Review of Books

Rethinking the Yellowbelt: Report Release

After a full year of research, the largest, most comprehensive report on the economics, politics, history, and policies of zoning in Toronto is available for download.

The full report is available both on the Housing Matters website, and quickly downloadable here: Rethinking the Yellowbelt.

The “Yellowbelt” refers to the portion of the city that’s zoned exclusively for detached homes. The report goes into detail explaining when and why such a zone came into existence, where it spreads in the city, who is hurt by the existence of this zone and how; and what it will take to change the system.

A summary of the report follows. Of course, the report itself goes into much more detail.

Romance Econometrics

I had a mentor at BYU, Prof. James McDonald, who tried to convince us that

- Econometrics is Fun.

- Econometrics is Easy.

- Econometrics is Your Friend.

One of his classes made a bronze plaque out of it for him. He also tried to convince us that Economics is Romantic because this one guy took a girl to his class on a date and she married him anyway. Because he was one of the economists I’ve tried to model my life after, I’ve always been on the lookout for ways to convince people that econometrics is, in fact, fun, friendly, easy, and romantic.

A while back, Bill Easterly blogged about how marriage search is like development, and in the process talking about how unromantic economists can be:

I recently helped one of my single male graduate students in his search for a spouse.

First, I suggested he conduct a randomized controlled trial of potential mates to identify the one with the best benefit/cost ratio. Unfortunately, all the women randomly selected for the study refused assignment to either the treatment or control groups, using language that does not usually enter academic discourse.

With the “gold standard” methods unavailable, I next recommended an econometric regression approach. He looked for data on a large sample of married women on various inputs (intelligence, beauty, education, family background, did they take a bath every day), as well as on output: marital happiness. Then he ran an econometric regression of output on inputs. Finally, he gathered data on available single women on all the characteristics in the econometric study. He made an out-of-sample prediction of predicted marital happiness. He visited the lucky woman who had the best predicted value in the entire singles sample, explained to her how he calculated her nuptial fitness, and suggested they get married. She called the police.

He goes on from there to describe how he eventually did find a mate and makes a comparison with development and over-reliance on econometric methods. As popular as it is in Libertarian circles to bash on econometrics, I’d like to defend empirics by pointing out that his regression advice was not sound:

1 – The suitor’s regressions ignored the self-selection bias. Regressions only tell us what the ‘average’ effects are, that is the effect for the ‘average’ person. Making the average guy happy is only relevant if he is the average guy. Economists being the strange lot we are, it is likely that it takes a special kind of person to marry one of us. He ought to have found a bunch of guys very similar to himself and examine the qualities that made a difference from among (and this is key) the population of women willing to marry guys like him – the women who self-select themselves into our group. If he then approached a women who was not in that group, no wonder he was rejected! I knew I had my work cut out for me since I was in junior high: a Latter-day Saint economist-in-embryo who read Shakespeare “in the original Klingon”, and who carried a briefcase to school? Small sample sizes indeed!

2 – He ignored endogeneity. Instead of trying to convince her that research showed she would make him happy, he needed to present research that demonstrated he would make her happy, and that’s the other half of the regression: male qualities on marital happiness. No wonder she rejected him: his regressions didn’t answer her question!

Personally, I took more of a Bayesian approach. Bayesians believe that a lot of things in life (like regression coefficients) are random and over time we get better and better signals about where the truth is, but we only ever approach it by degrees. First, by trying to become a friend, I identified if a woman was in the group of people who might marry someone like me. Each interaction gave me more information about the error term and the regression coefficients about fostering a happy, loving friendship that could endure. After any failed relationship, I had a new variable or two to add to my equations and I understood the ‘relationships’ between relationship variables better. That might be about finding out different things I needed (hunh, so her political affiliation isn’t as important as I thought and her willingness to smile at me is vital) or about learning more and better policies over time that I could enact to make her happier (tips for being a better listener or learn to identify her love languages and feed them to her regularly).

One of the most important regression-related romance tips I learned was to control the variables I could control, and leave the residual in God’s hands. I recall a graduate labor economics research seminar where the presenter claimed that the marriage market always cleared. I complained that I was willing to supply a great deal more marriage than had ever been demanded at prevailing prices. I was reassured that the marriage market clears in equilibrium, and I might not have found my equilibrium yet. The presenter’s prediction was, thankfully, prescient: I found a buyer a year later, and last week we celebrated 5250 days of married bliss.

Nightcap

- Charlemagne Chris Wickham, History Today

- Populism Simon Schama, Financial Times

- Harold Bloom (1930-2019) Flesch & Roth, n+1

- German supermarkets Rachel Lu, the Week

Nightcap

- The empty seat on a crowded Japanese train Baye McNeil, Japan Times

- Interstellar conversations Caleb Scharf, Scientific American

- Donald Trump is a weak man in a strongman’s world Ross Douthat, New York Times

- The Poland model: left-wing economic policy and right-wing social policy Anna Sussman, the Atlantic

Nightcap

- Nozick, State, and Reparations Irfan Khawaja, Policy of Truth

- No friends but the mountains Maurice Glasman, New Statesman

- The layers of Israel’s Trump mistake Michael Koplow, Ottomans & Zionists

- Why hasn’t Brexit happened? Christopher Caldwell, Claremont Review of Books