- We need to talk about the British Empire Sunder Katwala, CapX

- Nazi political economy Pseudoerasmus

- Liberty isn’t free Irfan Khawaja, Policy of Truth

- Institutional oceanography Chris Shaw, Libertarian Ideal

Affirmative Guilt-Gradient and the Overton Window in Identity-Based Pedagogy

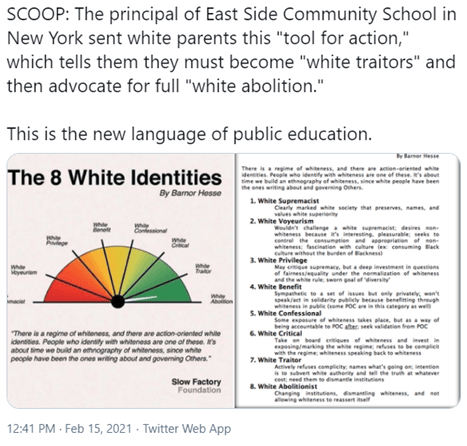

Yesterday, I came across this scoop on Twitter; New York Post and several other blogs have since reported it.

Regardless of this scoop’s veracity, the chart of Eight White identities has been around for some time now, and it has influenced young minds. So, here is my brief reflection on such identity-based pedagogy:

As a non-white resident-alien, I understand the history behind the United States’ racial sensitivity in all domains today. I also realize how zealous exponents of diversity have consecrated schools and university campuses in the US to rid the society of prevalent racial power-structures. Further, I appreciate the importance of people being self-critical; self-criticism leads to counter-cultures that balance mainstream views and enable reform and creativity in society. But I also find it essential that critics of mainstream culture don’t feel morally superior to enforce just about any theoretical concept on impressionable minds. Without getting too much into the right vs. left debate, there is something terribly sad about being indoctrinated at a young age —regardless of the goal of social engineering— to accept an automatic moral one-‘downmanship’ for the sake of the density gradient of cutaneous melanin pigment. Even though I’m a brown man from a colonized society, this kind of extreme ‘white guilt’ pedagogy leaves me with a bitter taste. And in this bitter taste, I have come to describe such indoctrination as “Affirmative Guilt-Gradient.”

You should know there is something called the Overton Window, according to which concepts grow larger when their actual instances and contexts grow smaller. In other words, well-meaning social interventionistas easily view each new instance in the decreasingly problematic context of the problem they focus on with the same lens as they consider the more significant problem. This leads to unrealistic enlargement of academic concepts that are then shoved down the throats of innocent, impressionable school kids who will take them as objective realities instead of subjective conceptual definitions overlaid on one legitimate objective problem.

I find the scheme of Eight White identities a symptom of the shifting Overton Window.

According to Thomas Sowell, there is a whole class of academics and intellectuals of social engineering who believe that when the world doesn’t reconcile to their pet theories, that shows something is wrong with the world, not their theories. If we are to project Thomas Sowell’s observation on this episode of “Guilt-Gradient,” it is perfectly reasonable to expect many white kids and their parents to refuse to adopt these theoretically manufactured guilt-gradient identities. We can then —applying Sowell’s observation—predict academics to declare that opposition to the “Guilt Gradient” is evidence for many covert white supremacists in the society who will not change. Such stories may then get blown up in influential Op-Eds, leading to the magnification of a simple problem, soon to be misplaced in the clutter of naïve supporters of such theories, the progressive vote-bank, and hard-right polemics.

We should all acknowledge that attachment to any identity—be it majority or minority—is by definition NOT a hatred for an outgroup. Assistant Professor of Political Science at Duke University, Ashley Jardina, in her noted research on the demise of white dominance and threats to white identity, concludes, “White identity is not, a proxy for outgroup animus. Most white identifiers do not condone white supremacism or see a connection between their racial identity and these hate-groups. Furthermore, whites who identify with their racial group become much more liberal in their policy positions than when white identity is associated with white supremacism.” Everybody has a right to associate with their identity, and equating one’s association with an ethnic majority identity is not automatically toxic. I feel it is destructive to view such identity associations as inherently toxic because it is precisely this sort of warped social engineering that results in unnecessary political polarization; the vicious cycle of identity-based tinkering is a self-fulfilling prophecy. Hence, recognizing the Overton Window at play in such identity-based pedagogy is a must if we have to make progress. We shouldn’t be tricked into assuming that the non acceptance of the Affirmative Guilt Gradient is a sign of our society’s lack of progress.

Finally, I find it odd that ideologues who profess “universalism” and international identities choose schools and universities to keep structurally confined, relative identities going by adding excessive nomenclature so they can apply interventions that are inherently reactionary. However, isn’t ‘reactionary’ a pejorative these ideologues use on others?

Afternoon Tea: Allegory of the Peace of Westphalia (1654)

This is by Jacob Jordaens, a Flemish painter, and it is not even one of his most famous paintings. Here’s Jordaens’ wiki page. The Peace of Westphalia ended the 30 Years War. The Habsburgs weren’t necessarily the bad guys. The Peace of Westphalia didn’t establish state sovereignty in a system of equal (in theory) nation-states within an interstate order. The Peace of Westphalia solved a religious constitutional question within the Holy Roman Empire and ended the war between the Dutch and the Spanish. The Westphalian state system that we speak of and live in today is not appropriately named. Here’s the best article (pdf) I’ve read on the Peace.

If we were to appropriately name the interstate order that we have today, it would be named the Napoleonic interstate system. Alas. It’s called the Westphalian system. The US, and a couple of other big states like China and Russia, have trouble fitting in to the “Westphalian” state system because they established their own regional state systems long before being wrangled into European imperial entanglements. It goes without saying that polities in Africa, Asia, and the Americas also had trouble fitting into the “Westphalian” state system.

What if one of the regional orders established by the US, Russia, or China were embraced as the new global order, instead of the “Westphalian” (really Napoleonic) system based on nation-state sovereignty? I don’t think this would be a bad thing, and in their own way, the US, China, and Russia have been trying to do this since the end of World War II.

Nightcap

- Who wants common sense? Robin Hanson, Overcoming Bias

- Theory versus common sense: the Dutch Notes On Liberty

- Scotland’s new blasphemy law Madeleine Kearns, L&L

- Academic corruption: government money Arnold Kling, askblog

Nightcap

- Fascinating piece on Ming China’s censorial system Branko Milanovic, globalinequality

- On the farmer’s protests Jeet Singh, Time

- Understanding the rise of socialism Brad Delong, Grasping Reality

- Understanding middlebrow Scott Sumner, Money Illusion

Nightcap

- The imperial sociology of “the tribe” in Afghanistan Nivi Manchanda, Millennium

- Life in the capital city of pre-modern Japan John Butler, Asian Review of Books

- The Irish free trade crisis of 1779 Joel Herman, Age of Revolutions

- Insiders and outsiders in 17th century philosophy Eric Schliesser, Philosophical Reviews

The Prose and Poetry of Creation

Every great civilization has simultaneously made breakthroughs in the natural sciences, mathematics, and in the investigation of that which penetrates beyond the mundane, beyond the external stimuli, beyond the world of solid, separate objects, names, and forms to peer into something changeless. When written down, these esoteric percepts have the natural tendency to decay over time because people tend to accept them too passively and literally. Consequently, people then value the conclusions of others over clarity and self-knowledge.

Talking about esoteric percepts decaying over time, I recently read about the 1981 Act the state of Arkansas passed, which required that public school teachers give “equal treatment” to “creation science” and “evolution science” in the biology classroom. Why? The Act held that teaching evolution alone could violate the separation between church and state, to the extent that this would be hostile to “theistic religions.” Therefore, the curriculum had to concentrate on the “scientific evidence” for creation science.

As far as I can see, industrialism, rather than Darwinism, has led to the decay of virtues historically protected by religions in the urban working class. Besides, every great tradition has its own equally fascinating religious cosmogony—for instance, the Indic tradition has an allegorical account of evolution apart from a creation story—but creationism is not defending all theistic religions, just one theistic cosmogony. This means there isn’t any “theological liberalism” in this assertion; it is a matter of one hegemon confronting what it regards as another hegemon—Darwinism.

So, why does creationism oppose Darwinism? Contrary to my earlier understanding from the scientific standpoint, I now think creationism looks at Darwin’s theory of evolution by natural selection not as a ‘scientific theory’ that infringes the domain of a religion but as an unusual ‘religion’ that oversteps an established religion’s doctrinal province. Creationism, therefore, looks to invade and challenge the doctrinal province of this “other religion.” In doing so, creation science, strangely, is a crude, proselytized version of what it seeks to oppose.

In its attempt to approximate a purely metaphysical proposition in practical terms or exoterically prove every esoteric percept, this kind of religious literalism takes away from the purity of esotericism and the virtues of scientific falsification. Therefore, literalism forgets that esoteric writings enable us to cross the mind’s tempestuous sea; it does not have to sink in this sea to prove anything.

In contrast to the virtues of science and popular belief, esotericism forces us to be self-reliant. We don’t necessarily have to stand on the shoulders of others and thus within a history of progress, but on our own two feet, we seek with the light of our inner experience. In this way, both science and the esoteric flourish in separate ecosystems but within one giant sphere of human experience — like prose and poetry.

In a delightful confluence of prose and poetry, Erasmus Darwin, the grandfather of Charles Darwin, wrote about the evolution of life in poetry in The Temple of Nature well before his grandson contemplated the same subject in elegant prose:

Organic life beneath the shoreless waves

Was born and nurs’d in Ocean’s pearly caves;

First forms minute, unseen by spheric glass,

Move on the mud, or pierce the watery mass;

These, as successive generations bloom,

New powers acquire, and larger limbs assume;

Whence countless groups of vegetation spring

And breathing realms of fin, and feet, and wing.

The prose and poetry of creation — science and the esoteric; empirical and the allegorical—make the familiar strange and the strange familiar.

Nightcap

- Great piece on Latin American history Laurence Blair, BBC History

- The political economy of deep integration (pdf) Maggi & Ossa, NBER

- Democracy in the polycentric city (pdf) Loren King, Journal of Politics

- Here’s what I don’t say Christopher Craig, Threepenny Review

The poverty of the middle-class: lack of savoir-faire

In 2009, the film An Education came out. It was a Bildungsroman of sorts but it was beyond a coming-of-age story. It showed the life of the aspiring, post-World War II nouveau riche middle-class. The protagonist is a schoolgirl whose aspirationally-minded parents send her to a private school. They have no notion of what a good school is, how to tell if one is good, or why a person should attend one; they only know that “all the best” send their children to fee-paying schools. In the process, they’re swindled. The film’s characters descend into wallowing self-pity as nothing works out quite right for the protagonist. The story showcases a reality that we’re dealing with today. A fiction created by and for the post-War nouveau riche is collapsing. Those caught in its net do not recognize that what is collapsing is a fantasy, believing instead that the social order is declining, that a social contract has been broken.

Adam Smith wrote in his Theory of Moral Sentiments (1759),

The rich man glories in his riches, because he feels that they naturally draw upon him the attention of the world, and that mankind are disposed to go along with him in all those agreeable emotions with which the advantages of his situation so readily inspire him. At the thought of this, his heart seems to swell and dilate itself within him, and he is fonder of his wealth, upon this account, than for all the advantages it procures him. The poor man, on the contrary is ashamed of his poverty.

In the twenty-first century, achievement replaces riches as a font of glory. And that is good. It means that we have reached a point where being monied by itself is no longer a distinction. Achievement is the currency of the realm now (if anyone wants to imagine me saying that in the voice of Cutler Beckett from Pirates of the Caribbean, please feel free). What we face today is a society of rich men whose hearts have dilated but who haven’t reinvested their wealth to procure advantage. And herein lies the rub: procuring advantage requires savoir-faire and those who built and benefitted from the society of post-War nouveau riche for the better part don’t have it.

The savoir-faire needed is a type of street-smarts, but for life and careers rather than the literal streets (though it’s good to have that as well). This knowledge is not particularly secret, yet when caught out, the nouveau riche middle-class squawks and cries foul. Take for example Abigail Fisher and her lawsuit against UT-Austin: the young woman required the Supreme Court to validate UT-Austin’s assertion that graduating above average from a public school, playing in a section of a youth orchestra, and being one of two million Habitat for Humanity volunteers did not make her remarkable. The Abigail Fisher story is not one of racism or affirmative action. It’s a story of lack of savoir-faire. A person who thinks that any of the extracurriculars entered into evidence at the trial were résumé enhancing is as deluded as the parents from An Education who thought that merely forking out money ensured social mobility, a better life, the prospect of great things.

Making unfounded assumptions is part of the nouveau riche middle-class’ lack of savoir-faire. A lawyer I know has made it well into adulthood without knowing that advanced degrees from Ivy League schools are fully funded, i.e. free. Believing that he could neither afford an academic advanced degree nor that it would pay off professionally, he pursued law at a school where he received in-state tuition. He suffers from a stagnant career and fears that he doesn’t have a vocation for law. In contrast, this lawyer has already been surpassed by another attorney I know who is still in her twenties. In addition to being fiercely intelligent overall, she is worldly-wise. When she decided on law school, she pursued only Ivy Plus schools exactly because they were the ones with the best funding and scholarships; name recognition was an aside. She received merit-based full tuition funding, a stipend, and major professional opportunities because she was a prize winner.

Nor is it an anomaly that the highest tiers of education are free, or less expensive than people assume. Those who have read George Elliot’s Daniel Deronda know that Daniel was on track to win a fellowship which would refunded his tuition at Cambridge to his father Sir Hugo Mallinger. This was a huge honor which had almost nothing to do with money. Sir Hugo was fabulously wealthy; he didn’t need the money refunded – though of course it would have been nice. The honor was the primary attraction for him. “Daddy paid all my tuition” can’t be put on a résumé; “___ Fellow” or “winner of ___ Scholarship” can be. To be clear, I fully support parents saving for their children’s college. But I have had genuine conversations with people who told me that even though their children qualified for merit scholarships or grants, they wouldn’t apply for them because “those are for poor people.” The middle-middle class’ false pride of refusing to apply for scholarships and grants, euphemistically call “paying their way,” has only disadvantaged middle-middle class children as they arrive at the ages of twenty-two, twenty-four, twenty-six without plums, without proof of their abilities, without signs that someone, some institution took a bet on them and that they held up their end of the bargain. Further as Daniel Deronda’s story shows, this false pride has never been the way of the upper-class.

A lack of savoir-faire affects in career shaping as well. I know two artists, one of whom is quite young, just over thirty, and highly successful; the other has had an unnecessarily disappointing career. Artistically, both are remarkable. The difference between the two is that since undergraduate the first has submitted her work to art journals, competitions, galleries, any opportunity where her art could be seen. Acceptance rates are less than one percent, and it is entirely standard for artists to apply multiple times to a single opportunity. The first artist has learned to take rejection on the chin, get up, and reapply. She said to me once, “all grant applications want to know what journals you’ve been published in, what shows you’ve had and where; all the journals and competitions want to know what grants you’ve won, where you’ve been published, and what shows you’ve had. The only thing to do is to keep having shows, keep applying, keep building.” Her persistence shows as she wins more and more prizes which in turn lead to bigger opportunities. She’s already developed a name and reputation within the professional community.

In contrast, the second artist submitted her work to a handful of opportunities when she graduated but gave up when the everything ended in rejections. Now, decades later, she understands how the “numbers game” works, and she’s submitting her work for consideration again. Just because she “didn’t know” she has lost decades she could have spent building her professional reputation and career. She lives in a kind of disappointed daze, wondering why things never quite worked out. She’s reached the point where she can afford to support herself by art alone, but she feels as though somehow some vague, inchoate rules of the game have been broken.

This is not about having money. The artist who has drifted and the first lawyer both come from and have enough money to do anything they might desire. This is about knowing how things work. In the age of the internet, such ignorance and lack of savoir-faire is inexcusable, and it is only right for it to be treated as a flaw. Back in 1905, my great-grandfather who had grown up in unfathomable, though genteel, poverty managed to figure out that Harvard doctorates were fully funded. He pursued one to the benefit of himself and his children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren. If he could gather information and take action in 1905, in a part of the country without telephone, running water, electricity, or proper roads, what excuse is there for people today?

Gathering information and then taking action has another name: meritocracy. Both the left and the right have united against meritocracy, as predicted by Michael Dunlop Young, the man who coined the term “meritocracy.” Both sides agree that the meritocracy is bad because it is unfair, it breaks social bonds, however fictious. The rub with meritocracy is that it favors those who have savoir-faire over those who do not.And perhaps it is unfair. For example, the artists are equal in that each is technically strong and expresses interesting concepts with their art. Subjectively speaking, I would pay to go see the work of either of them in galleries. Yet one is ahead of the other in her career because she knew what was needed to cultivate her professional reputation and promote her work.

The second lawyer, the first artist, the UT-Austin students who had superb applications all earned their laurels because they took the extra steps of gathering information and learning how the world works. We owe nothing to people who won’t inform themselves, who create fictions about how the world around them works and then become angry when their ideas are shown to be fantasy. Saying that we are in a social contract with such people is coercive because such a contract compels those with savoir-faire to be the custodians of those without it. It would mean that Abigail Fisher would have to be admitted to the school of her choice because she “didn’t know” that all her extracurriculars were ordinary; it would mean that the first lawyer would have to be elevated to equality with the second one, even though the first one is literally less knowledgeable about the law, because he “didn’t know” that better quality legal training was in his grasp; it would mean that we would have to hold the artist who “didn’t know” to submit to journals and gallery competitions as equal to one who has a strong career and recognition because she submits her work regularly. How is this world, a society of excusing ignorance, pandering to an affluent but uninformed, uninquiring people, more fair than a meritocracy?

Nightcap

- The local touch of Soviet modernism Aliide Naylor, Jacobin

- The bad Muslim discount Kristin Yee, Asian Review of Books

- Ireland, America, and…national parks Melissa Buckheit, FIVES

- Can Japan bring the US back into the TPP? Daisuke Akimoto, Diplomat

In Pursuit Of The Human Aim Of Leisure

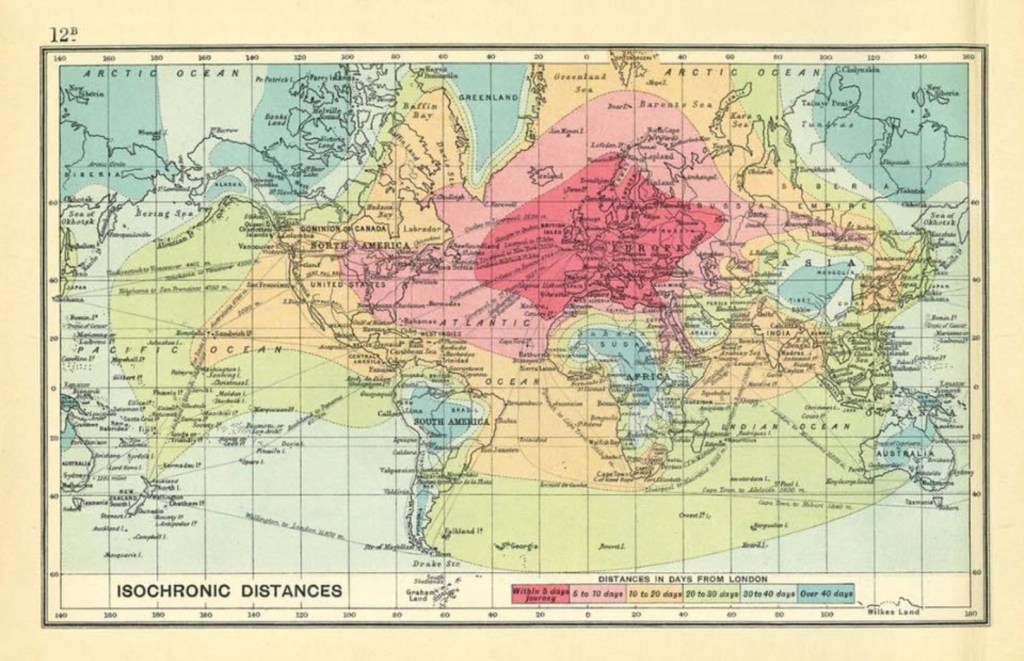

This fascinating isochrone map—how many days it took to get anywhere in the world from London in 1914—at first blush evokes the cliché that the world has now shrunk. Obviously it hasn’t shrunk. While the distance between London and New Delhi is still 4,168 miles, what has shrunk is time, and this has had profound aftermaths on our lives.

One of the great ironies in the remarkable proliferation of time-saving inventions is they haven’t made life simple enough to give us more time and leisure. By leisure, I don’t mean a virtue of some kind of inertia, but a deliberate organization based on a definite view of the meaning and purpose of life. In the urban world, the workweek hasn’t shortened. We still don’t have large swaths of time to really enjoy the good life with our families and friends.

In 1956, Sir Charles Darwin, grandson of the great Charles Darwin, wrote an interesting essay on the forthcoming Age of Leisure in the magazine New Scientist in which he argued: “The technologists, working for fifty hours a week, will be making inventions so the rest of the world need only work twenty-five hours a week. […] Is the majority of mankind really able to face the choice of leisure enjoyments, or will it not be necessary to provide adults with something like the compulsory games of the schoolboy?”

He is wrong in the first part. The world may have shrunk but cities have magnified. Travel technologies have incentivized us to live farther away and simply travel longer distances to work and attract anxiety attacks during peak hour traffic [Google Marchetti’s constant]. So, rather than being bored to death, our actual challenge is to avoid psychotic breakdowns, heart attacks, and strokes resulting from being accelerated to death.

Nonetheless, Sir Charles Darwin is accurate about “compulsory games” for adults. What else are social media platforms, compulsive eating, selfies, texts, Netflix bingeing, and 24/7 news media that dominate our lives? They are the real opiates of the masses. We have been so conditioned to search for happiness in these anodyne pastimes that defying these urges appears to be a denial of life itself. It is not surprising that we can no longer confidently tell the difference between passing pleasure and abiding joy. Lockdown or no lockdown, we are all unwittingly participating in these compulsory games with unwritten rules, believing that we are now that much closer to the good life of leisure. But are we?

‘Time is the wealth of change, but the clock in its parody makes it mere change and no wealth.’— Rabindranath Tagore

Nightcap

- The Mises-(Karl) Polanyi debate (on imperialism) reconsidered Eric Schliesser, Digressions & Impressions

- Racism, entrepreneurship, and love Conor Friedersdorf, Atlantic

- The new power brokers? Index funds and the public interest Sahand Moarefy, American Affairs

- The quiet collapse of Scottish unionism Scott Hames, New Statesman

Nightcap

- Should everything be decentralized? Arnold Kling, Pairagraph

- Is Russia’s future non-Slavic? Eugene Chausovsky, Newlines

- Is America’s future non-European? Samuel Gregg, Law & Liberty

- The myth of Westernization Jon Davidann, Aeon

Nightcap

- Libertarianism is bankrupt Thomas Wells, 3 Quarks Daily

- Neoracism in America today John McWhorter, Persuasion

- Racism, elites, and the have-nots Joanna Williams, spiked!

- Monday morning quarterbacking Jason Brennan, 200-Proof Liberals

Nightcap

- Middle class: questioning the definitions Mary Lucia Darst, NOL

- On Romney’s child allowance proposal Scott Sumner, EconLog

- On the American constitutionalism, and nationalism Dennis Coyle, Modern Age

- Ottomanism, nationalism, and republicanism (IV) Barry Stocker, NOL