- Caught between the Devil and the deep blue sea (Nigeria) Fisayo Soyombo, Al-Jazeera

- Jared Kushner and the art of humiliation (Palestine) Hirsh & Lynch, Foreign Policy

- “The Blob” and the Hell of good intentions (Washington) Christopher Preble, American Conservative

- How Africa is converting China (to Christianity) Christopher Rhodes, UnHerd

Nightcap

- Trump’s wall and the legal perils of “emergency powers” Ilya Somin, Volokh Conspiracy

- Can Trump spin a wall from nothing? Michael Kruse, Politico

- In defence of conservative Marxism Chris Dillow, Stumbling & Mumbling

- We must stand strong against the men who would be kings Charles Cooke, National Review

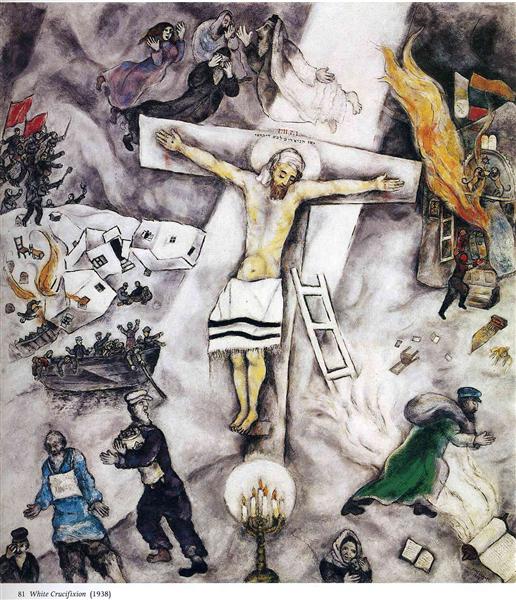

Afternoon Tea: White Crucifixion (1938)

From the esteemed Jewish French-Belarusian artist (and one of my personal favorites), Marc Chagall:

RCH: Calvin Coolidge

I took on Calvin Coolidge this week. My Tuesday column dealt with Coolidge and his use of the radio, while this weekend’s column argues why you should love him:

2. Immigration. At odds with the rest of his anti-racist administration, Coolidge’s immigration policy was his weakest link. Although he was not opposed to immigration personally, and although he used the bully pulpit to speak out in favor of treating immigrants with respect and dignity, Coolidge was a party man, and the GOP was the party of immigration quotas in the 1920s. Reluctantly, and with public reservations, Coolidge signed the Immigration Act of 1924, which significantly limited immigration into the United States up until the mid-1960s, when new legislation overturned the law.

Please, read the rest.

Nightcap

- The St. Valentine’s Day massacre Evan Bleier, RealClearLife

- The Sons of Mars and the ancient Mediterranean Erich Anderson, History Today

- The two trilemmas today Branko Milanovic, globalinequality

- How the United States reinvented empire Patrick Iber, New Republic

Nightcap

- A clash of the sacred and the secular Nader Hashemi, Liberty Forum

- The perks and perils of having a state-run church James Robinson, Cato Unbound

- Dutch pasts and the American archive Derek Kane O’Leary, JHIBlog

- Liberalism, democracy, and polarization Edwin van de Haar, NOL

Afternoon Tea: Last Supper (1903)

From the Russian painter Ilya Repin:

This is a bit different than the traditional “last supper” paintings we are used to, at least here in the States.

Nightcap

- Islam, blasphemy, and the East-West divide Mustafa Akyol, Liberty Forum

- Religious freedom and the modern state Koyama & Johnson, Cato Unbound

- Did Kongolese Catholicism lead to slave revolutions? Mohammed Elnaiem, JSTOR Daily

- Ottoman autocracy, Turkish liberty Barry Stocker, NOL

Monetary Progression and the Bitcoiner’s History of Money

In the world of cryptocurrencies there’s a hype for a certain kind of monetary history that inevitably leads to bitcoin, thereby informing its users and zealots about the immense value of their endeavor. Don’t get me wrong – I laud most of what they do, and I’m much looking forward to see where it’s all going. But their (mis)use of monetary history is quite appalling for somebody who studies these things, especially since this particular story is so crucial and fundamental to what bitcoiners see themselves advancing.

Let me sketch out some problems. Their history of money (see also Nick Szabo’s lengthy piece for a more eloquent example) goes something like this:

- In the beginning, there was self-sufficiency and the little trade that occurred place took place through barter.

- In a Mengerian process of increased saleability (Menger’s word is generally translated as ‘saleableness’, rather than ‘saleability’), some objects became better and more convenient for trade than others, and those objects emerged as early primative money. Normally cherry-pick some of the most salient examples here, like hide, cowrie shells, wampum or Rai stones.

- Throughout time, precious metals won out as the best objects to use as money, initially silver and gradually, as economies grew richer, large-scale payments using gold overtook silver.

- In the early twentieth century, evil governments monopolized the production of money and through increasingly global schemes eventually cut the ties to hard money and put the world on a paper money fiat standard, ensuring steady (and sometimes not-so-steady) inflation.

- Rising up against this modern Goliath are the technologically savvy bitcoiners, thwarting the evil money producing empires and launching their own revolutionary and unstoppable money; the only thing that stands in its way to worldwide success are crooked bankers backed by their evil governments and propaganda as to how useless and inapt bitcoin is.

This progressively upward story is pretty compelling: better money overtake worse money until one major player unfairly took over gold – the then-best money – replacing it with something inferior that the Davids of the crypto world now intents to reverse. I’m sure it’ll make a good movie one day. Too bad that it’s not true.

Virtually every step of this monetary account is mistaken.

First, governments have almost always defined – or at least seriously impacted – decisions over what money individuals have chosen to use. From the early Mesopotamian civilizations to the late-19th century Gold Standard that bitcoin is often compared to, various rulers were pretty much always involved. Angela Redish writes in her 1993 article ‘Anchors Aweigh’ that

under commodity standards – in practice – the [monetary] anchor was put in place not by fundamental natural forces but by decisions of human monetary authorities. (p. 778)

Governments ensured the push to gold in the 18th and 19th centuries, not a spontaneous order-decentralized Mengerian process: Newton’s infamous underpricing of silver in 1717, initiating what’s known as the silver shortage; Gold standard laws passed by states; large-scale network effects in play in trading with merchants in those countries.

Secondly, Bills of Exchange – ie privately issued debt – rather than precious metals were the dominant international money, say 1500-1900. Aha! says the bitcoiner, but they were denominated in gold or at least backed by gold and so the precious metal were in fact the real outside money. Nope. Most bills of exchange were denominated in the major unit of account of the dominant financial centre at the time (from the 15th to the 20th century progressively Bruges, Antwerp, Amsterdam and London), quite often using a ghost money, in reference to the purchasing power of a centuries-old coins or social convention.

Thirdly, monetary history is, contrary to what bitcoiners might believe, not a steady upward race towards harder and harder money. Monetary functions such as the medium of exchange and the unit of account were seldomly even united into one asset such as we tend to think about money today (one asset, serving 2, 3 or 4 functions). Rather, many different currencies and units of accounts co-emerged, evolved, overtook one another in response to shifting market prices or government interventions, declined, disappeared or re-appeared as ghost money. My favorite – albeit biased – example is early modern Sweden with its copper-based trimetallism (copper, silver, gold), varying units of account, seven strictly separated coins and notes (for instance, both Stockholms Banco and what would later develop into Sveriges Riksbank, had to keep accounts in all seven currencies, repaying deposits in the same currency as deposited), as well as governmental price controls for exports of copper, partly counteracting effects of Gresham’s Law.

The two major mistakes I believe bitcoiners make in their selective reading of monetary theory and history are:

1) they don’t seem to understand that money supply is not the only dimension that money users value. The hardness of money – ie, the difficulty to increase supply – as an anchoring of price levels or stability in purchasing power is one dimension of money’s quality – far from the only. Reliability, user experience (not you tech nerds, but normal people), storage and transaction costs, default-risk as well as network effects might be valued higher from the consumers’ point of view.

2) Network effects: paradoxically, bitcoiners in quibbling with proponents of other coins (Ethereum, ripple, dash etc) seem very well aware of the network effects operating in money (see ‘winner-takes-it-all’ arguments). Unfortunately, they seem to opportunistically ignore the switching costs involved for both individuals and the monetary system as a whole. Even if bitcoin were a better money that could service one or more of the function of money better than our current monetary system, that would not be enough in the presence of pretty large switching costs. Bitcoin as money has to be sufficiently superior to warrant a switch.

Bitcoiners love to invoke history of money and its progression from inferior to superior money – a story in which bitcoin seems like the natural next progression. Unfortunately, most of their accounts are lacking in theory, and definitely in history. The monetary economist and early Nobel Laureate John Hicks used to say that monetary theory “belongs to monetary history, in a way that economic theory does not always belong to economic history.”

Current disputes over bitcoin and central banking epitomize that completely.

Nightcap

- Intellectuals and a century of political hero worship William Anthony Hay, Modern Age

- John Stuart Mill: a not so secular saint James Smith, Los Angeles Review of Books

- Irving Babbitt’s history of ideas Simon Brown, JHIBlog

- Classical knowledge, lost & found: a history in seven cities David Abulafia, Literary Review

Automated law enforcement and rational basis

Does law enforcement need a human touch? The Supreme Court of Iowa says no. The Court recently decided that automated traffic enforcement (ATE) does not violate the Iowa Constitution. The Court, however, did take some time to address an important topic in constitutional jurisprudence: the nature of rational basis review.

Rational basis is a test applied to a variety of constitutional challenges. In the ATE case, the plaintiffs had brought due process and equal protection claims, both of which relied on the rational basis test. Rational basis is the weakest test in the hierarchy of judicial scrutiny. If a law is rationally related to a legitimate government interest, then a court won’t strike it down. As you might expect, plaintiffs very rarely succeed on this flimsy rational basis standard.

And so it was here. The Plaintiffs had argued that the ATE system in Cedar Rapids was not rationally related to an interest in public safety because, among many other things, the system punished a vehicle’s owner for speeding even if the owner was not the driver at the time. The Court had misgivings, but it ultimately deferred to the City and let the law slide.

The Court did, however, give a little boost to rational basis. The Court correctly noted that many state constitutions offer a stronger rational basis test than the federal test. That’s an important reminder to constitutional litigators–sometimes state constitutions may have analogous provisions to the federal constitution, but the protections they offer might be more robust.

The Court also made an important point about evidence in a rational basis claim. In many rational basis cases, plaintiffs don’t even get a chance to present evidence as to whether a law is rationally related to a legitimate government interest. If the government just asserts–without evidence–that a law furthers a legitimate interest like public safety, then the game is over. But the Iowa Supreme Court correctly noted that while a law is entitled to a presumption of constitutionality under rational basis, plaintiffs have a right to present evidence to rebut that presumption. Hence, “the mere incantation of the abracadabra of public safety does not end the analysis.” This evidentiary point is vital for strengthening the constitution’s protections against expansive government power.

Afternoon Tea: Christ on the Sea of Galilee (1854)

From Eugene Delacroix, as requested by Jacques Delacroix:

I could stare at this for hours…

Obscenity law liberalised

This is a cross-post from my contribution to the Adam Smith Institute blog.

Last week the Crown Prosecution Service published updated guidance for prosecutions under the Obscene Publications Act (1959). Legal campaigning has brought about a big change: the liberal tests of harm, consent and legality of real acts are now key parts of their working definition of obscenity. The CPS explain:

… conduct will not likely fall to be prosecuted under the Act provided that:

- It is consensual (focusing on full and freely exercised consent, and also where the provision of consent is made clear where such consent may not be easily determined from the material itself); and

- No serious harm is caused

- It is not otherwise inextricably linked with other criminality (so as to encourage emulation or fuelling interest or normalisation of criminality); and

- The likely audience is not under 18 (having particular regard to where measures have been taken to ensure that the audience is not under 18) or otherwise vulnerable (as a result of their physical or mental health, the circumstances in which they may come to view the material, the circumstances which may cause the subject matter to have a particular impact or resonance or any other relevant circumstance).

Nightcap

- UCLA and its new ideological litmus tests Erik Gilbert, Quillette

- Sovereignty and the Latin American experience Greg Grandin, London Review of Books

- How good is television as a medium of history? Castor, et al, History Today

- SETI’s charismatic megafauna Nick Nielsen, Centauri Dreams

From the Comments: Mexican communist art at San Francisco’s public colleges

My college (City College of San Francisco) has a “Diego Rivera Theater” featuring a mural by the artist that spans the width of the building. It is the cultural asset of which the college is most proud. It is very nice to look at. Here’s a picture.

That’s from David Potts, who teaches philosophy at City College of San Francisco and blogs at Policy of Truth.

I’ve seen the real thing. It’s absolutely beautiful. If you’re doing the tourist thing in San Francisco, or if you live there and are looking for something to do, make sure you hit up CCSF.