Note: A version of this was initially posted on my old, now defunct blog. However, has become increasingly relevant in the age of Trump, and is worthy of reconsideration now.

It’s one of the most common arguments against looser immigration going back to Milton Friedman to Donald Trump. It is commonly claimed that even though loosening immigration restrictions may be economically beneficial and just, it should be opposed due to the existence of the welfare state. Proponents of this claim argue that immigrants can simply come to this country to obtain welfare benefits, doing no good for the economy and adding to budget deficits.

Though this claim is on its face plausible, welfare is not nearly as much of a compelling reason to oppose immigration as so many argue. It is ultimately an empirical question as to whether or not the fiscal costs of immigration significantly outweigh the fiscal benefits of having more immigrants pay taxes and more tax revenue economic growth caused by immigration.

Before delving into the empirical studies on the matter, there is one very important fact that is too often neglected in these discussions: there are already heavy laws restricting all illegal immigrants and even the vast majority of legal ones from receiving Welfare. As the federal government itself–specifically the HHS–notes:

With some exceptions, “Qualified Aliens” [ie., legal immigrants] entering the country after August 22, 1996, are denied “Federal means-tested public benefits” for their first five years in the U.S. as qualified aliens.

If we were to allow more immigrants, there are legal mechanisms stopping them from getting welfare. There are some exceptions and even unlawful immigrants occasionally slip through the cracks, but this is already a major hole in the case that welfare means we should hold off on immigration reform. The vast majority of immigrants cannot receive welfare until years after they are legalized.

However, for the sake of argument, let us ignore that initial hole in the case against increased immigration. Let’s generously assume the majority of immigrants–legal and illegal–can somehow get their hands on welfare. There is still little reason to expect that additional immigrants would be any more of a fiscal drag on welfare programs for the vast majority of our population simply because they are not the type of people who typically wind up on welfare. Our welfare programs are primarily designed to protect a select few types of people: the sick and elderly (Social Security and Medicare), and women and children (SCHIP, SNAP, TAMPF, etc.) If one looks at the demographics of immigrants coming into the country, however, one finds that they do not fit in the demographics of those who typically qualify for welfare programs. According to the Census Bureau, the vast majority (75.6%) of the total foreign-born population (both legal and illegal immigrants) are of working age (between 25 and 65). Most immigrants, even if they were legal citizens, would not qualify for most welfare programs to begin with.

On the other hand, poverty rates are higher among immigrants and that means more would qualify for poverty-based programs. However, most immigrants are simply not the type to stay in those programs. Contrary to common belief, immigrants are mostly hard-working innovators rather than loafing welfare queens. According to Pew Research, 91% of all unauthorized immigrants are involved in the US labor force. Legal immigrants also start businesses at a higher rate than natural born citizens and file patents at almost double the rate of natives. As a result, immigrants have fairly high social mobility, especially intergenerationally, and so will not stay poor and on welfare all that long.

Put it together, and you find that immigrants generally use many major welfare programs at a lower rate than natives. Immigrants are 25% less likely to be enrolled in Medicare, for example, than citizens and actually contribute more to Medicare than they receive while citizens make Medicare run at a deficit. From the New York Times:

[A] study, led by researchers at Harvard Medical School, measured immigrants’ contributions to the part of Medicare that pays for hospital care, a trust fund that accounts for nearly half of the federal program’s revenue. It found that immigrants generated surpluses totaling $115 billion from 2002 to 2009. In comparison, the American-born population incurred a deficit of $28 billion over the same period

Of course, nobody would advocate restrictions on how many children are allowed to be born based on fiscal considerations. However, for some reason the concern becomes a big factor for immigration skeptics.

If you are still not convinced, let us go over the empirical literature on how much immigrants cost fiscally. Some fairly partisan studies, such as this one from the Heritage Foundation (written by an analyst who was forced to resign due to fairly racist claims), conclude that fiscal costs are very negative. The problem, however, is that most of these studies fail to take into account the dynamic macroeconomic impact of immigration. Opponents of immigration, especially those at the Heritage Foundation, generally understand the importance of taking dynamic economic impacts of policy changes into account on other issues, e.g. taxation; however, for some (partisan) reason fail to apply that logic to immigration policies. Like taxes, immigration laws change people’s behavior in ways that can increase revenue. First of all, more immigrants entering the economy immediately means more revenue as there are more people to tax. Additionally, economic growth from further division of labor provided by immigration increases tax revenue. Any study that does not succeed in taking into account revenue gains from immigration is not worth taking seriously.

Among studies that are worth taking seriously, there is general consensus that immigrants are either a slight net gain fiscally speaking, a very slight net loss or have little to no impact. According to a study by the OECD of its 20 member countries, despite the fact that some of its countries have massive levels of immigration, the fiscal impact of immigration is “generally not exceeding 0.5 percent of G.D.P. in either positive or negative terms.” The study concluded, “The current impact of the cumulative waves of migration that arrived over the past 50 years is just not that large, whether on the positive or negative side.”

Specifically for the United States, another authoritative study in 1997 found the following as summarized by David Griswold of the Cato Institute:

The 1997 National Research Council study determined that the typical immigrant and descendants represent an $80,000 fiscal gain to the government in terms of net present value. But that gain divides into a positive $105,000 fiscal impact for the federal government and a negative $25,000 impact on the state and local level (NRC 1997: 337).

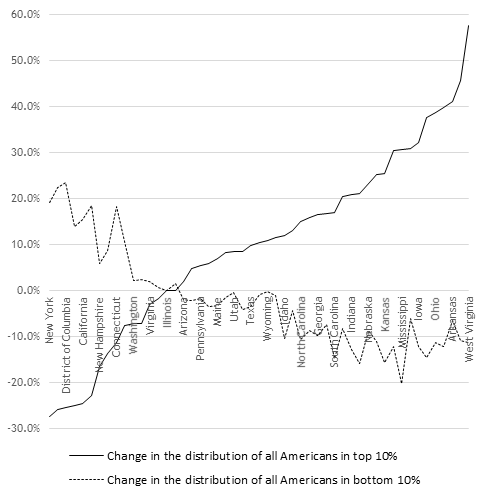

Despite the slight negative impact for states, as Griswold notes, there is no correlation between immigration and more welfare for immigrants:

Undocumented immigrants are even more likely to self-select states with below-average social spending. Between 2000 and 2009, the number of unauthorized immigrants in the low-spending states grew by a net 855,000, or 35 percent. In the high-spending states, the population grew by 385,000, or 11 percent (U.S. Census 2011; NASBO 2010: 33; Passel and Cohn 2011). One possible reason why unauthorized immigrants are even less drawn to high-welfare-spending states is that, unlike immigrants who have been naturalized, they are not eligible for any of the standard welfare programs.

The potential fiscal impact of immigration from the Welfare state is not a good reason to oppose it at all. There are major legal barriers to immigrants receiving welfare, immigrants are statistically less likely to receive welfare than natives for demographic reasons, and all the authoritative empirical evidence shows that immigrants are on net not a very significant fiscal drag and can, in fact, be a net fiscal gain.