Humankind’s struggle with moral is of course nothing new, it rather inherent to our nature to revolt against the meaningless world and the manmade system of reason. Furthermore, moral values vary over a specific period of time swinging from rather high moral standards to very low ones. Regarding morality as an abstract compass guiding our thought, goals and behaviour, Economist, in general, are not known for dealing in depth with the metaphysical reason behind our behaviour yet they explore and explain human actions through our surrounding incentives, which also structure and direct our action. Economist such as Daron Acemoglu & James Robinson or William J. Baumol have explored these changes in human behaviour through changing incentive structures thoroughgoingly.

However, folks mourning the moral decline of today’s west often fail to provide concrete evidence for their argument. They either cherry-pick events or legislatures to infer a macro trend inductively or they lose themselves in difficult language trying to somehow save their argument by making it incomprehensible. I cannot help feeling that mourning the moral decay of the west has somehow become a shibboleth for eloquently expressing the “Things used to be way better back then” narrative. However, I admit that there were probably a couple of sociological papers who have covered this issue very well which I am unaware of. Contrary, the public debate was dominated by a few grumpy intellectuals holding the above-named attitude. I was recently provided with a very concrete set of indicators to measure moral decline while digging through Samuel P. Huntington’s infamous classic “The clash of civilization” from 1996. He states that there are five main criteria which indicate the ongoing decline of moral values in the West. [1]

After being provided with a concrete framework to quantify the moral decline of the west, I was keen to see how the moral decline of the west has developed in the 20 years since the book has first been published in 1996. Although I also take issue with some of these indicators to measure moral decline, I avoid any normative judgement in the first part and just look at their development over time. Furthermore, since Samuelson himself mostly takes data from the USA representing the West, I might as well do so too for the sake of simplicity. So, let’s see what happened to moral values in the West in the last years by checking each of Huntington’s indicator one by one.

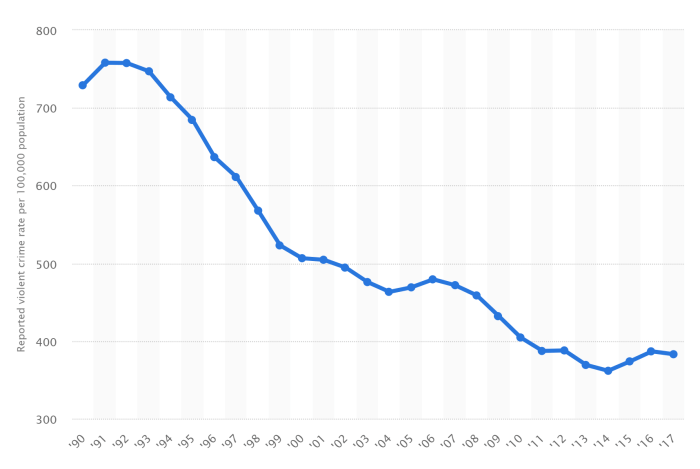

1. Increasing antisocial behaviour such as acts of crime, drug use and general violence

Apart from the global long-term trend of declining homicides, we can also observe a recent downward trend in the reported violent crime rate since 1990 in the USA. Scholars agree that the crime rate is in an extreme decline. Expanding the realm towards Europe, you will see similar results (see here).

Source: Statista

Source: Statista

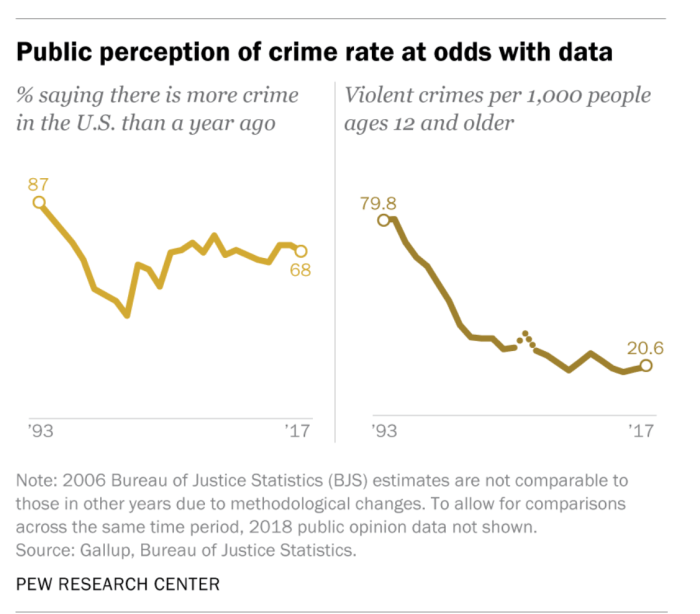

Despite these trends, the public (as well as some intellectuals as well I assume) vastly still holds a distorted perception of the crime rate. The sharp decline in actual crimes strongly contradicts the fact that a majority of the people still uphold the myth of increasing crime rates.

Regarding drug use in the USA, it is important to mention that the absolute amount of illicit drugs consumed has slightly gone up since 1990. This development is mostly driven by an increasing consumption of marijuana: “Use of most drugs other than marijuana has stabilized over the past decade or has declined.”, states the National Institute on drug abuse in 2015.

Contrary, the number of deadly injections are increasing. However, the share of the population with drug use disorders has remained on the same level of 5.3% over the last 20 years.

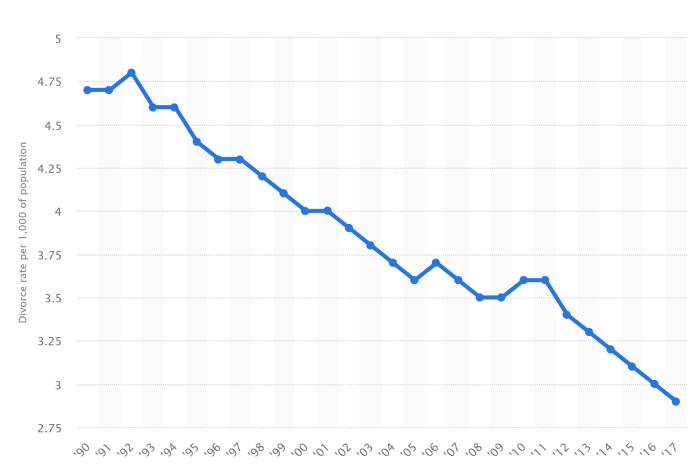

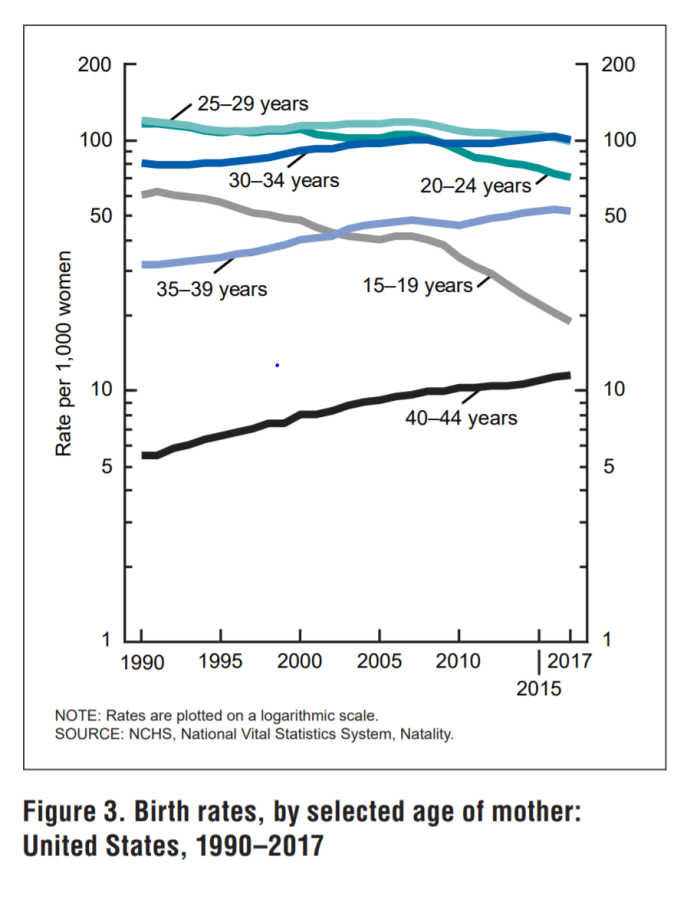

2. Decay of the family resulting in increasing divorce rates, teenage motherhood and single parents

It is hard to measure the “Decay of the family” itself. Luckily, Huntington further concretizes his claim by naming some of the measurable effects. There is nothing much to do to refute these statement except for looking at the following graphs.

a) Firstly, the divorce rate is sharply declining.

Source: Statista

b) Second, teenage pregnancy rates are also dropping since 1990.

Source: National Vita Statistics Report

Source: National Vita Statistics Report

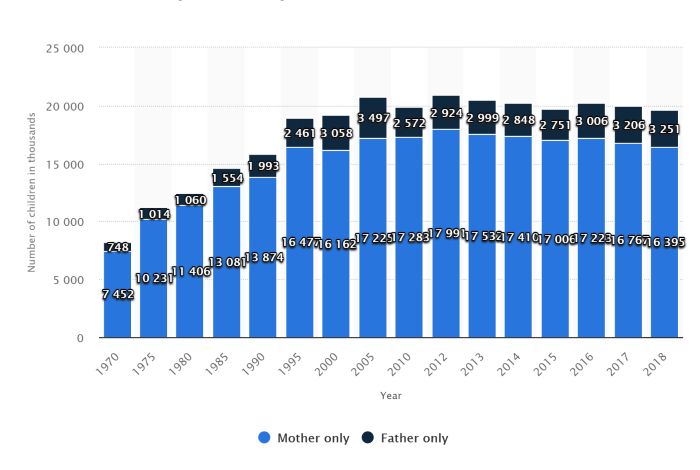

c) Third, the number of Americans living in single parenthood is not increasing drastically since 1990.

Source: Statista

Source: Statista

I often take issue when (especially conservative) scholars mourn the declining importance of family. Even if there are certain indicators which would back up Huntington’s claims, he does not name them himself. While it is indeed true that “family” as an institution is undergoing changes, there is no evidence (at least named by Huntington) to back up the claim of a decline of its importance.

3. Declining “social capital” and voluntarism leading to less trust.

It is indeed true, that the adult volunteering rate declined from early 2000 to 2016 from 27.4% to 24.9%. Interestingly, it recently bounced back to a new high in 2018, hitting the 30% target. Really the only point where one must agree to Huntington’s claim is the decrease of interpersonal trust as well as trust in public institutions. This trend is indeed very worrisome considering that trust is a major factor for flourishing societies.

4. The decline in work ethic

The research here is a little bit tricky and points in both directions. Although there has been wide academic coverage of the millennial work ethic scholars could not find a consensus on this issue. Its is especially difficult to extract the generational influence from other key determinants of work ethic, such as position or age. Academics warn to mistake the ever-ongoing conflict between young vs. old with the Boomer vs. Millenial conflict. I haven’t settled my opinion on this one. These Articles from Harvard Business Review and Psychology Today provide a good overview of both sides of the medal.

5. Less general interest in Education

This indicator is particularly interesting for me because as a member of the 90’ generation, I have experienced quite the opposite in Germany. But let’s have a look at the data.

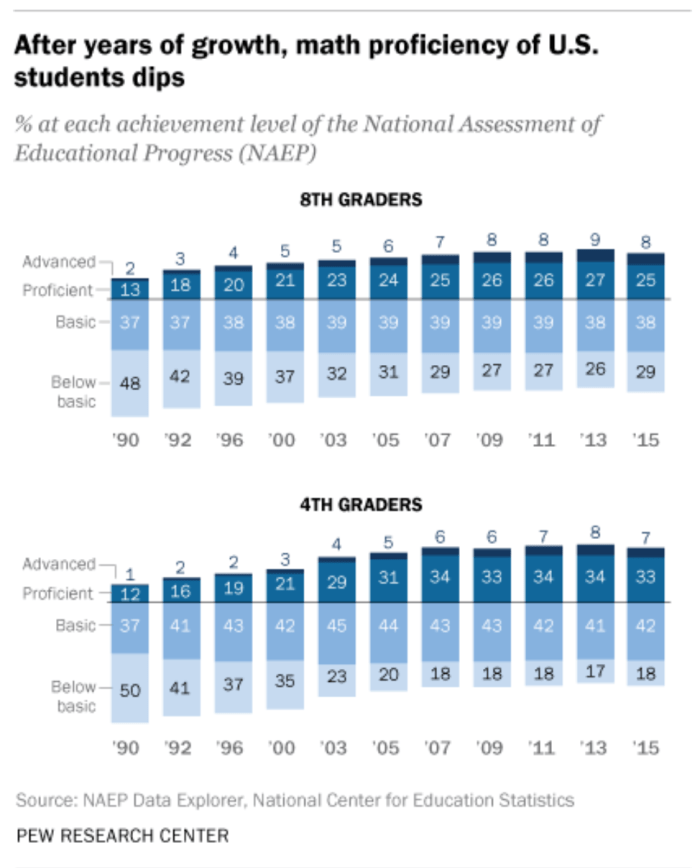

Despite ranking only in the middle in a global country comparison, the US students still made a huge leap in terms of maths and reading proficiency, which only slowed down in 2015:

Source: Pew Research Center

Furthermore, the overall educational level of the USA continues to rise, resulting in the fact that “the percentage of the American population age 25 and older that completed high school or higher levels of education reached 90% [for the first time ] in 2017.” Contrary, there are still major differences when one looks at features like race or parent household (See here), but the overall trajectory of the educational level is sloping upwards.

What do these criteria measure?

As you can see, there is little to no evidence to empirically back up the claim of western moral decay. Furthermore, while many case studies have shown that lack of interpersonal trust, lack of education or a declining work ethic can pose a great threat to society, I refuse to see a connection (a no known to me study disproves me here) between (recreational) drugs consumption, alternative family models, increasing hedonism and moral decline. Thus I believe that many advocates of the moral decay theory regard it as an opportunity to despise developments they personally do not like. I do not imply that everyone arguing for the moral decline of the west is unaware of the global macro-trends which heavily improved our life, but I highly doubt their assumption, that we are currently in a short-to-medium term “moral recession”. Even when one upholds the very conservative statements such as drug consumption adding to moral decline, is hard to argue that we are currently witnessing a moral decay of the west. Contrary, It may be true that Huntington has observed something different in the period before publishing “The clash of civilization” in 1996. Of course, I myself witness the ongoing battle against norms on the increasing hostility towards the intellectual enemy in the west, but one should always keep in mind the bigger picture. Our world is getting better – in the long- and in the short-run; There is no such thing as a moral decline of the West.

[1] Huntington, Samuel P. (2011): Kampf der Kulturen. Die Neugestaltung der Weltpolitik im 21. Jahrhundert. Vollst. Taschenbuchausg., 8. Aufl. München: Goldmann (Goldmann, 15190). P. 500