A few weeks ago, I finished reading Scott Sumner’s The Midas Paradox. As an economic historian, I must say that this is by far the best book on the Great Depression since the Monetary History of the United States. Moreover, it is the first book that I’ve read that argues simply that the Great Depression was the result of a sea of poor (and sometimes good) policy decisions. However, coming out of the book, there was one thing that came to mind: Sumner is underselling his (very strong) case.

In essence, the argument of Sumner looks considerably like that of Milton Friedman and Anna Schwartz: The Federal Reserve allowed the money supply to contract dramatically up to 1932, turning what would have been a mild recession into a depression. However, Sumner adds a twist to this. He mentions that after the depth of the monetary contraction had been reached, there was a reflation allowing an important recovery during 1933. This is standard AS-AD macro of a (very late) expansionary policy to allow demand to return to equilibrium. Normally, that would have been sufficient to allow the rebound. Basically, this is the best case for NGDP targeting: never let nominal expenditures fall below a certain path because of a fall in demand. The problem, according to Sumner, is that the recovery was thwarted by poor supply-side policies (like the National Industrial Recovery Act, the Agricultural Adjustment Act etc.). The positive effects of the policy were overshadowed by poor policy. And thus, the depression continued.

To be fair, Sumner is not the first to emphasize the “real” variables side of the Great Depression. I am especially fond of the work of Richard Vedder and Lowell Galloway, Out of Work, which is a very strong candidate for being the first econometric assessment of the effects of poor supply-side policies during the Great Depression. I was also disappointed (but not too much since Sumner did not need to make this case) to see that no mention was made of the Smoot-Hawley tariff as a channel for monetary transmission (as Allan Meltzer argued back in 1976) of the contraction. Nonetheless, Sumner is the first to bring this case so cogently as a story of the Great Depression. Thus, these small issues do not affect the overall potency of his argument.

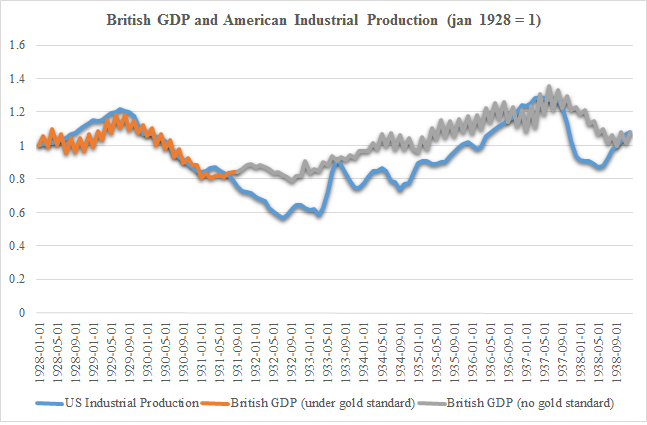

The problem, as I mentioned earlier, is that Sumner is underselling his case! I base this belief on the experience of England at the same time. Unlike the United States, the British decided to apply their piss-poor supply-side policies during the 1920s – well before the depression. The seminal paper (see this one too) on this is by Stephen Broadberry (note: I am very biased in favor of Broadberry given that he is my doctoral supervisor) who argued that the supply shocks of the 1920s caused substantial drops in hours worked and although the rise of unemployment benefits played a minor role, the vast majority of the causes were due to the legal encouragement of cartel formation. As a result, there were no supply-side shocks during the depression to create noise. However, England did have a demand-side expansionary policy in 1931. Even if it was by accident more than by design, England left the gold standard in September 1931. This led to the equivalent of an easy monetary policy and the British economy stopped digging and expanded afterwards. The Great Depression was not a pleasant experience for the British, but it was not even close to the dreadful situation in the United States. As a result, we can see whether or not it was possible to exit the Great Depression by virtue of a monetary policy. I’ve combined the FRED dataset on monthly industrial production and the monthly GDP estimates for inter-war Britain produced by Mitchell, Solomou and Weale (see here) to see what happened in England after it left the gold standard. As one can see, the economy of Britain rebounded much more magnificently than that of the United States in spite of supply-side constraints.

Sumner should expand on this point! To be fair, he does talk about it briefly. Not enough! A longer discussion of the British case provides him with the “extra mile” to cover the distance against competing theories. The absence of supply shocks in Britain during the Depression confirm his story that the woes of the United States during the 1930s are due to initially poor monetary policy and then poor supply-side policies. In my eyes, this is a strong confirmation of the importance of the NGDP level target argument!

With such a point made, it is easy to imagine a reasonable counterfactual scenario of what economic growth would have been after monetary easing in 1933 in the absence of supply-side shocks. Had the United States kept very unregulated labor and product markets, it is quite reasonable to believe (given the surge seen in 1933 in the Industrial Production data) that the United States would have returned to 1929 levels. In the absence of such a prolonged economic crisis, it is hard to imagine how different the 1930s and 1940s would have been but it is hard to argue that things would have been worse.

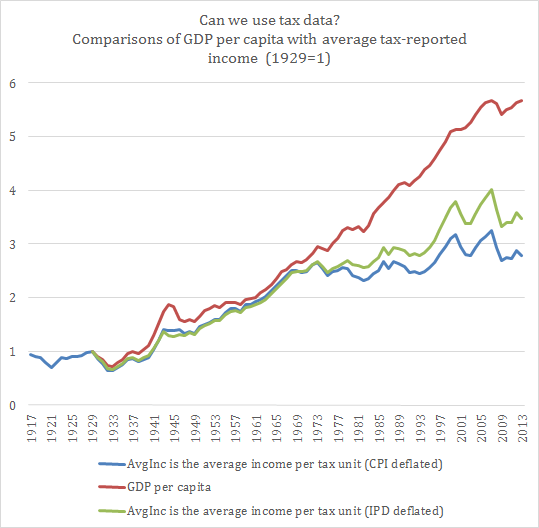

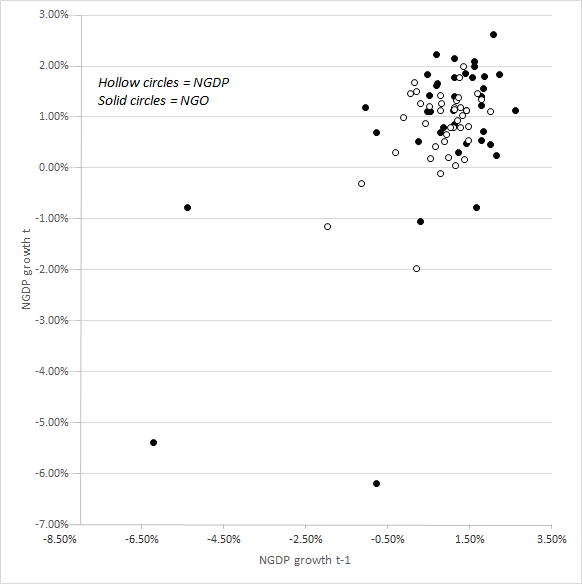

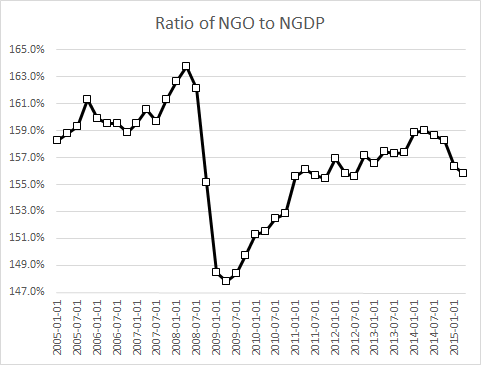

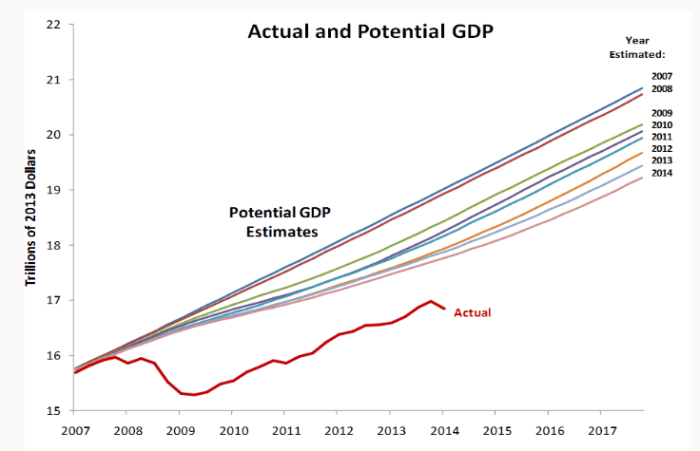

UPDATE: From the blog Historinhas, Marcus Nunes sent me the graph below confirming the importance of the NIRA shock on eliminating all the benefit from easy money after 1933.