- Things I hate about the US constitution Ilya Somin, Volokh Conspiracy

- At the Khmer Rogue tribunal MG Zimeta, London Review of Books

- Reductionism and anti-reductionism about painting Irfan Khawaja, Policy of Truth

- A foreign policy for the Left Samuel Moyn, Modern Age

Month: August 2018

Nightcap

- The dark side of war propaganda Bradley Anderson, American Conservative

- Is internationalism liberal or imperialist? Arnold Kling, askblog

- Internationalism is federalist, Arnold! Brandon Christensen, NOL

- ISIS and Sykes-Picot Nick Nielsen, The View from Oregon

A short note on Brazil’s elections

In October Brazilians will elect the president, state governors, and senators and congressmen, both at the state and the national level. It’s a lot.

There is clearly a leaning to the right. The free market is in the public discourse. A few years ago most Brazilians felt embarrassed to be called right wing. Today especially people under 35 feel not only comfortable but even proud to be called so.

The forerunner for president is Jair Bolsonaro. The press, infected by some form of cultural Marxism, hates Bolsonaro. Bolsonaro’s interviews in Brazilian media are always dull and boring. Always the same questions. The journalists decided that Bolsonaro is misogynist, racist, fascist, guitarist, and apparently, nothing will make them change their minds. Of course, nothing could be further from the truth. Bolsonaro is a very simple person, with very simple language, language that can sound very crude. But I defy anyone to prove he is any of these things. Also, Bolsonaro is one of the very few candidates who admits he doesn’t know a lot about economics. That’s great news! Dilma Rousseff lied that she had a Ph.D. in economics (when she actually didn’t have even an MA), and we all know what happened. Bolsonaro is happy to delegate economics to Paulo Guedes, a Brazilian economist enthusiastic about the Chicago School of Milton Friedman. One of Bolsonaro’s sons is studying economics in Institute Von Mises Brazil.

It is very likely that Brazil will elect a record number of senators and congressmen who will also favor free market.

Even if Bolsonaro is not elected, other candidates like Marina Silva and Geraldo Alckmin favor at least an economic model similar to the one Fernando Henrique Cardoso implemented in the 1990s. Not a free market paradise, but much better than what we have today.

Unless your brain has been rotten by cultural Marxism, the moment is of optimism.

RCH: death and taxes

I’ve been so busy I forgot about my Tuesday column over at RealClearHistory (I have a Friday column, too). Last week’s column was about the trial and execution of two Italian-born anarchists in Massachusetts:

The anarchism of Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti was left-wing and violent. Very violent. The two young men were admirers of Luigi Galleani, an Italian anarchist who advocated violence as the best way to achieve a more anarchist world. Sacco and Vanzetti, the executed, were part of an American syndicate dedicated to Galleani’s ideals. This syndicate was responsible for bombings, assassination attempts, printing and distributing bomb-making books, and even mass poisonings in the United States. The Galleanists were so violent that they sat atop a list of the federal government’s most dangerous enemies. On April 15, 1920, an armed robbery at the Slater and Morrill Shoe Company in Braintree, Mass., went awry and two men, a guard and an accountant (“paymaster”) were killed by the robbers. Sacco and Vanzetti were accused, convicted, and sentenced to death.

This week’s column focused on Shays’ Rebellion:

The Shaysites, as supporters of Daniel Shays came to be known, eventually grew to thousands of men, and the movement grew confident enough that it planned to seize a federal armory. However, the governor of Massachusetts, James Bowdoin, directed a local militia leader (William Shepard) to protect the armory. The armory, though, was federal property, and the militia was operating under state direction, so the seizure of the armory in the name of protecting it from rebels had the potential to ignite a powder keg of legal ramifications throughout the war-torn eastern seaboard.

Y’all stay sane out there!

Nightcap

- In Japan, ghost stories are not to be scoffed at Christopher Harding, Aeon

- Montesquieu was the ultimate revisionist Henry Clark, Law & Liberty

- Did British merchants cause the Opium War? Jeffrey Chen, Quillette

- The eclipse of Catholic fusionism Kevin Gallagher, American Affairs

Philosophy of science and free speech

Here’s a link to an article I wrote just published in FEE.

I consider this part of an ongoing, gradual effort to incorporate Paul Feyerabend into the liberty canon. It’s probably a mistake, but I’m doing it anyway.

I also want to give a shoutout to the person that commented I’m “pretending that Ayn Rand didn’t exist.” Of course I know what Ayn Rand is, that’s the island next to Great Britain.

Nightcap

- What do we mean by “meaning”? Scott Sumner, Money Illusion

- The Sōseki of Prague Duncan Stuart, 3:AM Magazine

- The Civic Sacred Cow Wayland Hunter, Liberty Unbound

- The (American) Civil War’s Most Infamous Atrocity Rick Brownell, Historiat

The Catholic Church, Pedophilia, and Gay Rights

Note: I wrote this eight (8) years ago, in April, on my personal blog, Facts Matter.

The Catholic Church is, first of all, a criminal organization. It conspired for several generations to shield criminals from justice, just like the Mafia. Reading the press, I experience a sense of growing disbelief. Many commentators sound as if it the Catholic Church should be given a pass, somehow. The reverse is true. I am not religious but I know enough about the traditional Jesus to remember that he held hypocrites in special contempt. (Within the context of his day, he called them “Pharisees,” a sect known for showing off instead of acting righteously.) The Catholic Church’s own historical, philosophical, and moral claims demand that its crimes be treated with special severity. The Catholic Church deserves enhanced penal sentences and seizure of property.

If you are a grief-stricken Catholic and you hesitate to leave the Church, you should wonder whether even your simple passivity does not make you complicit in the large-scale, systemic, criminal cover-up becoming apparent right now. If you believe that the Catholic Church has the ability to cleanse itself somehow, you have not been listening to the shameful lies and self-deceptions expressed by prelates, during Holy Week of all times.

As always, I pay attention to what one should reasonably expect to happen and that is not happening. It’s striking how nearly none of the accusations of pedophilia against the Catholic church concerns girls. Catholic sexual crimes against children are almost exclusively homosexual. It looks like we are speaking about thousands of homosexual crimes. It makes me wonder why I don’t hear a word from so-called “gay” organizations. I mean militant gay organizations. I do not (not) refer here to the many homosexuals who lead irreproachable and constructive lives. They have no more to do with priestly pedophilia than I am responsible for heterosexuals who cut up their wives into little pieces. Nevertheless, anyone who thinks that mass molestation of children by homosexuals within the church has no bearing on the discussion of homosexuals’ right to marry is dreaming. The numbers are just too large and the criminals are homosexuals, anyway you look at it.

Nightcap

- The science war Peter Boettke, Coordination Problem

- On wider access to culture Chris Dillow, Stumbling & Mumbling

- Spaceship Earth explores Culture Space Robin Hanson, Overcoming Bias

- The liberal dream is freedom plus groceries (and that’s okay) Brad DeLong, Grasping Reality

A Millennial’s New Perspective on Home Ownership

The last few years I’ve loudly protested that home ownership is overrated; it’s a bad investment plus lots of responsibility. And yet, this summer my fiance and I bought a 100 year old house on the south shore of Long Island.

Yes, I have lost my mind.

I basically stand by my earlier position, but with greater nuance. Owning a home is a complicated undertaking. But it’s given me a greater appreciation for the nuance involved in managing real estate.

Home ownership is a great big Gordian knot of inter-dependencies. It’s massive set of knowledge problems wrapped in externality problems.There’s a massive role for local knowledge which means policy makers’ attention should be less focused on things like home ownership rates, and more on guiding the right people into the right places to take advantage of that local knowledge.

With local knowledge comes local politics. I don’t know anything about local politics, but expect more posts about what’s going on in my town hall over the next few decades.

So what have I learned in this first month of home ownership?

- There’s something to be said about pride in ownership

It’s still a real trip to turn on my lights in my kitchen so I can do my laundry in my laundry machines. I didn’t think I’d enjoy it this much. The endowment effect is real. One effect has been to increase my interest in contributing to local public goods via civic engagement and other routes.

I haven’t been to a town hall meeting yet, but I plan on going to one tomorrow. I suspect it will be awful. But I’m walking distance, so I’ll be a little bit drunk.

- The real estate market has some serious frictions

This might be obvious, but it’s interesting. There are artificial and natural obstacles to the efficient use of real estate. Transaction costs are significant and property rights issues are hairy.

Buying a house is a complicated transaction and going through the process has really made clear to me how difficult it is to commodify land. Each piece of land has a unique location and history. Information asymmetries are substantial. The neighborhood you’re buying into is utterly out of your control. Put simply: Amazon won’t be selling real estate any time soon.

Part of the reason I’m happy with buying a house is that our rent had been increasing about $100/month/year. Land lords absolutely take advantage of real estate frictions to charge as much as they can. The alternative (which I chose) is to lock-in to a specific property.

- The required knowledge to operate a home is significant and difficult to evaluate.

It takes a lot of knowledge to manage a house. If I were to take a wild guess (at this non-quantifiable variable), I’d say that between 5% and 50% of a homeowner’s brain is necessary to operate a house. Even if you bring in experts to do everything, evaluating those experts is a lot of work.

There are repairs and upgrades to make, and my formal education prepared me for exactly none of those projects. On the other hand, I’ve got the Internet. Without YouTube and Reddit I’d be a half dozen unlucky mistakes away from homelessness.

On the other other hand, I’ve learned a ton of stuff I’ve got no use for. Like how to grow asparagus (which it turns out it isn’t worth doing except out of boredom).

You can’t evaluate knowledge until it’s too late. And there’s more to learn than you ever will, so you have to make mistakes. It’s true of home ownership and it’s true of life more generally.

- Gardening is a real trip.

In History of Economic Thought professor Gonzalez shared a story about two economists meeting in Switzerland during WWII. On showing his vegetable garden to the visiting economist, the visitor said “that’s not a very efficient way to grow food,” to which the gardener said, “yes, but it’s a very efficient way to grow utility.”

I’ve wanted to garden for some time, but the market for gardens is thin. So now I’m starting with almost no useful experience. My public stance has been that lawns are boring and dumb. But figuring out how to manage a little ecosystem ain’t easy. I now get why someone would just put in a lawn and be done with it.

At my old apartment complex the entire ecosystem was made of: humans, trees, lawns, cockroaches. I suspect the cockroaches did so well because all their competition was poisoned away. As an emergent order guy, I’m not really into that. But I get it now. In the same way the king wants everyone living in neat little taxable rows my life would be easier if I could just slash and burn all the complexity out of my yard.

Tl;dr: My biggest surprise as a new home owner is just how big a cognitive load owning a house is. You hear homeowners talk about how much work it can be, but I think it’s rare to hear someone talk about how much know-how is required.

Given the capacity to generate externalities, I’m a bit surprised that there isn’t more public policy devoted to issues of home ownership* (beyond subsidizing finance and increasing barriers to entry). I supposed I’ll learn a lot more about these issues as I learn about local politics.

*That isn’t to say I think it’s a good idea to get the government involved in trying to tell people how to go about the business of daily life. I think homeowners are (basically) doing fine left to their own devices.

The State and education – Part IV: Conclusion

On August 17, 2018, the BBC published an article titled “Behind the exodus from US state schools.” After taking the usual swipes at religion and political conservatism, the real reason for the haemorrhage became evident in the personal testimony collected from an example mother who withdrew her children from the public school in favour of a charter school:

I once asked our public school music teacher, “Why introduce Britney Spears when you could introduce Beethoven,” says Ms. Helmi, who vouches for the benefits to her daughters of a more classical education.

“One of my favourite scenes at the school is seeing a high-schooler playing with a younger sibling and then discussing whether a quote was from Aristotle or Socrates.”

The academic and intellectual problems with the state school system and curriculum are perfectly encapsulated in the quote. The hierarchy of values is lost, not only lost but banished. This is very important to understand in the process of trying to safeguard liberty: the progenitors of liberty are not allowed into the places that claim to incubate the supposed future guardians of that liberty.

In addition to any issues concerning academic curricula, there is the problem of investment. One of the primary problems I see today, especially as someone who is frequently asked to give advice on application components, such as résumés and cover letters/statements of purpose, is a sense of entitlement vis-à-vis institutional education and the individual; it is a sense of having a right to acceptance/admission to institutions and career fields of choice. In my view, the entitlement stems from either a lack of a sense of investment or perhaps a sense of failed investment.

On the one hand as E.S. Savas effectively argued in his book Privatization and Public-Private Partnerships, if the state insists on being involved in education and funding institutions with tax dollars, then the taxpayers have a right to expect to profit from, i.e. have a reasonable expectation that their children may be admitted to and attend, public institutions – it’s the parents’ money after all. On the other hand, the state schools are a centralized system and as such in ill-adapted to adjustment, flexibility, or personal goals. And if all taxpayers have a right to attend a state-funded institution, such places can be neither fully competitive nor meritocratic. Additionally, Savas’ argument serves as a reminder that state schooling is a manifestation of welfarism via democratic socialism and monetary redistribution through taxation.

That wise investing grants dividends is a truth most people freely recognize when discussing money; when applied to humans, people start to seek caveats. Every year, the BBC runs a series on 100- “fill-in-the-blank” people – it is very similar to Forbes’ lists of 30 under 30, top 100 self-made millionaires, richest people, etc. Featured on the BBC list for 2017 was a young woman named Camille Eddy, who at age 23 was already a robotics specialist in Silicon Valley and was working to move to NASA. Miss Eddy’s article begins with a quote: “Home-schooling helped me break the glass ceiling.” Here is what Eddy had to say about the difference between home and institutional schooling based on her own experience:

I was home-schooled from 1stgrade to high school graduation by my mum. My sister was about to start kindergarten, and she wanted to invest time in us and be around. She’s a really smart lady and felt she could do it.

Regarding curriculum choices, progress, and goals:

My mum would look at how we did that year and if we didn’t completely understand a subject she would just repeat the year. She focused on mastery rather than achievement. I was able to make that journey on my own time.

And the focus on mastery rather than achievement meant that the latter came naturally; Eddy tested into Calculus I her first year at university. Concerning socialization and community – two things the public schools pretend to offer when confronted with the fact that their intellectual product is inferior, and their graduates do not achieve as much:

Another advantage was social learning. Because we were with mum wherever she went we met a lot of people. From young to old, I was able to converse well with anyone. We had many friends in church, our home-school community groups, and even had international pen pals.

When I got to college I felt I was more apt to jump into leadership and talk in front of people because I was socially savvy.

On why she was able to “find her passion” and be an interesting, high-achieving person:

And I had a lot of time to dream of all the things I could be. I would often finish school work and be out designing or engineering gadgets and inventions. I did a lot of discovery during those home-school years, through documentaries, books, or trying new things.

In the final twist to the plot, Camille Eddy, an African-American, was raised by a single mother in what she unironically describes as a “smaller town in the US” where the “cost of living was not so high.” What Eddy’s story can be distilled to is a parent who recognized that the public institutions were not enough and directly addressed the problem. All of her success, as she freely acknowledges, came from her mother’s decision and efforts. In the interest of full honesty, I should state that I and my siblings were home-schooled from 1stgrade through high school by parents who wanted a full classical education that allowed for personal growth and investment in the individual, so I am a strong advocate for independent schooling.

There is a divide, illustrated by Eddy’s story, created by the concept of investment. When Camille Eddy described her mother as wanting “to invest time in us and be around,” she was simply reporting her mother’s attitude and motivation. However, for those who aspire to have, or for their children to attain, Eddy’s achievements and success, her words are a reproach. What these people hear instead is, “my mother cared more about me than yours cared about you,” or “my mother did more for her children than you have done for yours.” With statements like Eddy’s, the onus of responsibility for a successful outcome shifts from state institutions to the individual. The responsibility always lay with the individual, especially vis-à-vis public education since it was designed at the outset to only accommodate the lowest common denominator, but, as philosopher Allan Bloom, author of The Closing of the American Mind,witnessed, ignoring this truth became an overarching American trait.

There are other solutions that don’t involve cutting the public school out completely. For example: Dr. Ben Carson’s a single-, working-mother, who needed the public school, if only as a babysitter, threw out the TV and mandated that he and his brother go to the library and read. As a musician, I know many people who attended public school simply to obtain the requisite diploma for conservatory enrollment but maintain that their real educations occurred in their private preparation – music training, especially for the conservatory level, is inherently an individualistic, private pursuit. But all the solutions start with recognizing that the public schools are inadequate, and that most who have gone out and made a success of life in the bigger world normally had parents who broke them out of the state school mould. In the case of Dr. Carson’s mother, she did not confuse the babysitter (public school) with the educator (herself as the parent).

The casual expectation that the babysitter can also educate is part of the entitlement mentality toward education that is pervasive in American society. The mentality is rather new. Allan Bloom described watching it take hold, and he fingered the Silent Generation – those born after 1920 who fought in World War II; their primary historical distinction was their comparative lack of education due to growing up during the Great Depression and their lack of political and cultural involvement, hence the moniker “silent”[1]– as having raised their children (the Baby Boomers) to believe that high school graduation conferred knowledge and rights. As a boy Bloom had had to fight with his parents in order to be allowed to attend a preparatory school and then University of Chicago, so he later understandably found the entitlement mentality of his Boomer and Generation X students infuriating and offensive. The mental “closing” alluded to in Bloom’s title was the resolute refusal of the post-War generations either to recognize or to address the fact that their state-provided educations had left them woefully unprepared and uninformed.

To close, I have chosen a paraphrase of social historian Neil Howe regarding the Silent Generation, stagnation, and mid-life crises:

Their [Gen X’s] parents – the “Silent Generation” – originated the stereotypical midlife breakdown, and they came of age, and fell apart, in a very different world. Generally stable and solvent, they headed confidently into adult lives about the time they were handed high school diplomas, and married not long after that. You see it in Updike’s Rabbit books – they gave up their freedom early, for what they expected to be decades of stability.

Implicit to the description of the Silent Generation is the idea, expressed with the word “handed,” that they did not earn the laurels on which they built their futures. They took an entitlement, one which failed them. There is little intrinsic difference between stability and security; it is the same for freedom and liberty. History demonstrates that humans tend to sacrifice liberty for security. Branching out from education, while continuing to use it as a marker, we will look next at the erosive social effect entitlements have upon liberty and its pursuit.

[1]Apparently to be part of the “Greatest Generation,” a person had to have been born before or during World War I because, according to Howe, the Greatest Generation were the heroes – hero is one of the mental archetypes Howe developed in his Strauss-Howe generational theory – who engineered the Allied victory; the Silent Generation were just cogs in the machine and lacked the knowledge, maturity, and experience to achieve victory.

Nightcap

- What would it take to build a tower as high as outer space? Sun & Popescu, Aeon

- Progressive/libertarian: the alliance that isn’t Bryan Caplan, EconLog

- An atlas of diplomacy Francis Sempa, Asian Review of Books

- How to save the Catholic Church Rachel Lu, the Week

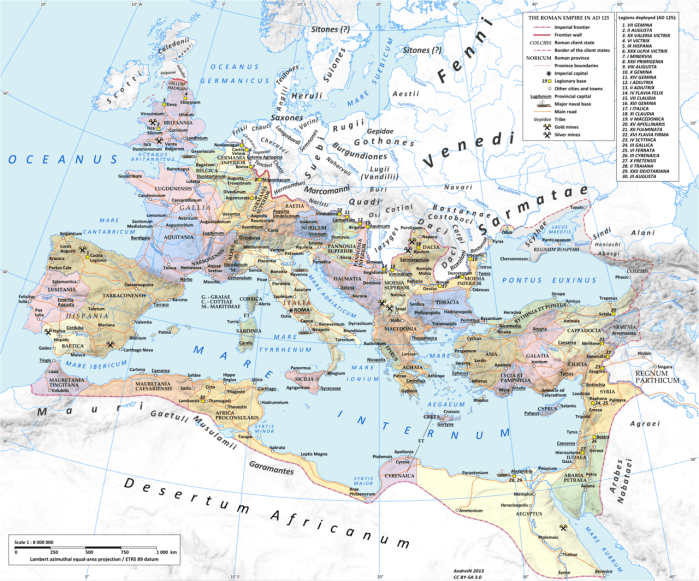

Eye Candy: the provinces of ancient Rome

This is a beautiful map of Rome’s administrative units. There’s not much more to say, really.

Here is Barry on Roman law. Here is Mark on the Roman economy. Have a good week!

Nightcap

- The transformation of the liberal political tradition in the nineteenth century Pamela Nogales, Age of Revolutions

- Kurds have conditions for an alliance with Shiites in Iraq Omar Sattar, Al-Monitor

- Mau-Mauing Myself Harry Stein, City Journal

- Is the sharing economy exploitative? Per Bylund, Power & Market

RCH: 10 libertarian thoughts on the (American) Civil War

I went there. I did it. I dropped a doo-doo right in the middle of August, for all the world to see. An excerpt:

5. Shout-outs to Alexis de Tocqueville and Joseph Smith. Alexis de Tocqueville wrote the best book on America, ever. Joseph Smith founded the “American religion” (to quote Leo Tolstoy). Both men also saw that the north-south divide in the United States was bound to lead to future calamity. It wouldn’t be accurate to call their thoughts on the American divide “predictions,” but both men were outsiders in one form or another, and both men have etched their names into history. The French, who had lost Tocqueville just two years prior to the beginning of the Civil War, approach to the American bloodbath was to remain neutral (after consulting with the United Kingdom), and instead invade Mexico. Napoleon III invaded Mexico, in the name of free trade, late in 1861 and established a puppet monarchy, which angered the United States as it violated the Monroe Doctrine. However, there was not much the U.S. could do and Napoleon III did not abandon his puppet until early 1866, when it became apparent which side was victorious in the American Civil War. The French preferred normalized relations with the American republic to a puppet monarch in the Mexican one. The Mormons, for their part, largely sat out the Civil War. Volunteers from Utah helped guard the mail routes from Indian attacks, but other than that, the Mormons, who had not yet been assimilated into American society (indeed, they had only fled from violence in Missouri to Utah a few decades prior to the Civil War), were content to let both sides bleed.

Please, read the rest.