As we are now solidly into 2018, I thought that it would be a good idea to underline the best articles in economic history that I read in 2017. Obviously, the “best” is subjective to my preferences. Nevertheless, it is a worthy exercise in order to expose some important pieces of research to a wider audience. I limited myself to five articles (I will do my top three books in a few weeks). However, if there is an interest in the present post I will publish a follow-up with another five articles.

O’Grady, Trevor, and Claudio Tagliapietra. “Biological welfare and the commons: A natural experiment in the Alps, 1765–1845.” Economics & Human Biology 27 (2017): 137-153.

This one is by far my favorite article of 2017. I stumbled upon it quite by accident. Had this article been published six or eight months earlier, I would never have been able to fully appreciate its contribution. Basically, the authors use the shocks induced by the wars of the late 18th century and early 19th century to study a shift from “self-governance” to “centralized governance” of common pool resources. When they speak of “commons” problems, they really mean “commons” as the communities they study were largely pastoral communities with area in commons. Using a difference-in-difference where the treatment is when a region became “centrally governed” (i.e. when organic local institutions were swept aside), they test the impact of these top-down changes to institutions on biological welfare (as proxied by infant mortality rates). They find that these replacements worsened outcomes.

Now, this paper is fascinating for two reasons. First, the authors offer a clear exposition of its methodology and approach. They give just the perfect amount of institutional details to assuage doubts. Second, this is a strong illustration of the points made by Elinor Ostrom and Vernon Smith. These two economists emphasize different aspects of the same thing. Smith highlights that “rationality” is “ecological” in the sense that it is an iterative process of information discovery to improve outcomes. This includes the generation of “rules of the game” which are meant to sustain exchanges. These rules need not be formal edifices. They can be norms, customs, mores and habits (generally supported by the discipline of continuous dealings and/or investments in social-distance mechanisms). On her part, Ostrom emphasized that the tragedy of the commons can be resolved through multiple mechanisms (what she calls polycentric governance) in ways that do not necessarily require a centralized approach (or even market-based approaches).

In the logic of these two authors, attempts at “imposing” a more “rational” order (from the perspective of the planner of this order) may backfire. This is why Smith often emphasizes the organic nature of things like property rights. It also shows that behind seemingly “dumb” peasants, there is often the weight of long periods of experimentation in order to adapt rules and norms in order to fit the constraints faced by the community. In this article, we can see those two things – the backfiring and, by logical implication, the strengths of the organic institutions that were swept away.

Fielding, David, and Shef Rogers. “Monopoly power in the eighteenth-century British book trade.” European Review of Economic History 21, no. 4 (2017): 393-413.

In this article, the authors use a legal change caused by the end of the legal privileges of the Stationers’ Company (which amounted to an easing of copyright laws). The market for books may appear to be “non-interesting” for mainstream economics. However, this would be a dramatic error. The “abundance” of books is really a recent development. Bear in mind that the most erudite monk of the late middle ages had less than fifty books from which to draw knowledge (this fact is a vague recollection of mine from Kenneth Clark’s art history documentary from the late 1960s which was aired by the BBC). Thus, the emergence of a wide market for books – which is dated within the period studied by the authors of this article – should not be ignored. It should be considered as one of the most important development in western history. This is best put by the authors when they say that “the reform of copyright law has been regarded as one of the driving forces behind the rise in book production during the Enlightenment, and therefore a key factor in the dissemination of the innovations that underpinned Britain’s Industrial Revolution”.

However, while they agree that the rising popularity of books in the 18th century is an important historical event, they contest the idea that liberalization had any effect. They find that the opening up of the market to competition had little effects on prices and book production. They also find that mark-ups fell but that this could not be attributed to liberalization. At first, I found these results surprising.

However, when I took the time to think about it I realized that there was no reason to be surprised. First, many changes have been heralded as crucial moments in history. More often than not, the importance of these changes has been overstated. A good example of an overstated change has been the abolition of the Corn Laws in England in the 1840s. The reduction in tariffs, it is argued, ushered Britain into an age of free trade and falling food prices.

In reality, as John Nye discusses, protectionist barriers did not fall as fast as many argued and there were reductions prior to the 1846 reform as Deirdre McCloskey pointed out. It also seems that the Corn Laws did not have substantial effects on consumption or the economy as a whole (see here and here). While their abolition probably helped increase living standards, it seems that the significance of the moment is overstated. The same thing is probably at play with the book market.

The changes discussed by Fielding and Rogers did not address the underlying roots of the level of market power enjoyed by industry players. In other words, it could be that the reform was too modest to have an effect. This is suggested by the work of Petra Moser. The reform studied by Fielding and and Rogers appears to have been short-lived as evidenced by changes to copyright laws in the early 19th century (see here and here). Moser’s results point to effects much larger (and positive for consumers) than those of Fielding and Rogers. Given the importance of the book market to stories of innovation in the industrial revolution, I really hope that this sparks a debate between Moser and Fielding and Rogers.

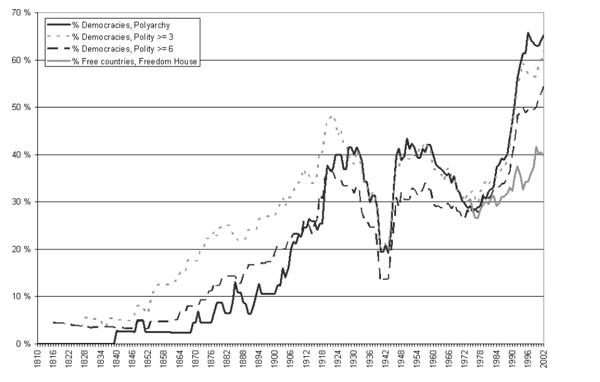

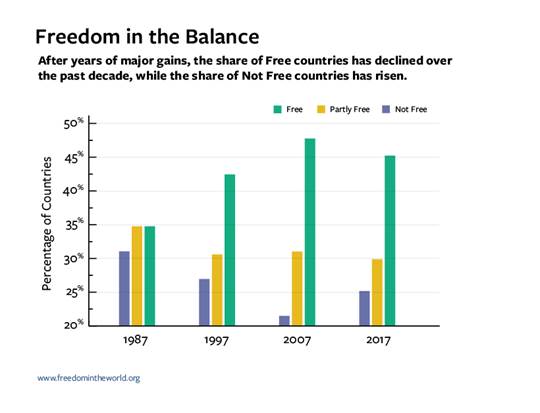

Johnson, Noel D., and Mark Koyama. “States and economic growth: Capacity and constraints.” Explorations in Economic History 64 (2017): 1-20.

I am biased as I am fond of most of the work of these two authors. Nevertheless, I think that their contribution to the state capacity debate is a much needed one. I am very skeptical of the theoretical value of the concept of state capacity. The question always lurking in my mind is the “capacity to do what?”.

A ruler who can develop and use a bureaucracy to provide the services of a “productive state” (as James Buchanan would put it) is also capable of acting like a predator. I actually emphasize this point in my work (revise and resubmit at Health Policy & Planning) on Cuban healthcare: the Cuban government has the capacity to allocate large quantities of resources to healthcare in amounts well above what is observed for other countries in the same income range. Why? Largely because they use health care for a) international reputation and b) actually supervising the local population. As such, members of the regime are able to sustain their role even if the high level of “capacity” comes at the expense of living standards in dimensions other than health (e.g. low incomes). Capacity is not the issue, its capacity interacting with constraints that is interesting.

And that is exactly what Koyama and Johnson say (not in the same words). They summarize a wide body of literature in a cogent manner that clarifies the concept of state capacity and its limitations. In doing so, they ended up proposing that the “deep roots” question that should interest economic historians is how “constraints” came to be efficient at generating “strong but limited” states.

In that regard, the one thing that surprised me from their article was the absence of Elinor Ostrom’s work. When I read about “polycentric governance” (Ostrom’s core concept), I imagine the overlap of different institutional structures that reinforce each other (note: these structures need not be formal ones). They are governance providers. If these “governance providers” have residual claimants (i.e. people with skin in the game), they have incentives to provide governance in ways that increased the returns to the realms they governed. Attempts to supersede these institutions (e.g. like the erection of a modern nation state) requires dealing with these providers. They are the main demanders of constraints which are necessary to protect their assets (what my friend Alex Salter calls “rights to the realm“). As Europe pre-1500 was a mosaic of such governance providers, there would have been great forces pushing for constraints (i.e. bargaining over constraints).

I think that this is where the literature on state capacity should orient itself. It is in that direction that it is the most likely to bear fruits. In fact, there have been some steps taken in that direction For example, my colleagues Andrew Young and Alex Salter have applied this “polycentric” narrative to explain the emergence of “strong but limited states” by focusing on late medieval institutions (see here and here). Their approach seems promising. Yet, the work of Koyama and Johnson have actually created the room for such contributions by efficiently summarizing a complex (and sometimes contradictory) literature.

Bodenhorn, Howard, Timothy W. Guinnane, and Thomas A. Mroz. “Sample-selection biases and the industrialization puzzle.” The Journal of Economic History 77, no. 1 (2017): 171-207.

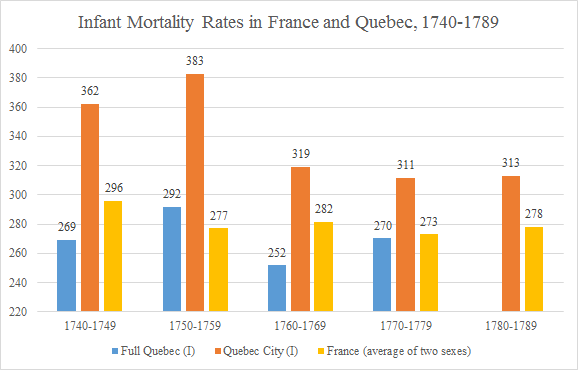

Elsewhere, I have peripherally engaged discussants in the “antebellum puzzle” (see my article here in Economics & Human Biology on the heights of French-Canadians born between 1780 and 1830). The antebellum puzzle refers to the possibility that the biological standard of living (e.g. falling heights, worsening nutrition, increased mortality risks) fell while the material standard of living increased (e.g. higher wages, higher incomes, access to more services, access to a wider array of goods) during the decades leading to the American Civil War.

I am inclined to accept the idea of short-term paradoxes in living standards. The early 19th century witnessed a reversal in rural-urban concentration in the United States. The country had been “deurbanizing” since the colonial era (i.e. cities represented an increasingly smaller share of the population). As such, the reversal implied a shock in cities whose institutions were geared to deal with slowly increasing populations.

The influx of people in cities created problems of public health while the higher level of population density favored the propagation of infectious diseases at a time where our understanding of germ theory was nill. One good example of the problems posed by this rapid change has been provided by Gergely Baics in his work on the public markets of New York and their regulation (see his book here – a must read). In that situation, I am not surprised that there was a deterioration in the biological standard of living. What I see is that people chose to trade-off shorter wealthier lives against longer poorer lives. A pretty legitimate (albeit depressing) choice if you ask me.

However, Bodenhorn et al. (2017) will have none of it. In a convincing article that has shaken my priors, they argue that there is a selection bias in the heights data – the main measurement used in the antebellum puzzle debate. Most of the data on heights comes either from prisoners or enrolled volunteer soldiers (note: conscripts would not generate the problem they describe). The argument they make is that as incomes grow, the opportunity cost of committing a crime or of joining the army grows. This creates the selection bias whereby the sample is going to be increasingly composed of those with the lowest opportunity costs. In other words, we are speaking of the poorest in society who also tended to be shorter. Simultaneously, fewer tall individuals (i.e. rich individuals) committed crimes or joined the army because incomes grew. This logic is simple and elegant. In fact, this is the kind of data problem that every economist should care about when they design their tests.

Once they control for this problem (through a meta-analysis), the puzzle disappears. I am not convinced by the latter part of the claim. Nevertheless, it is very likely that the puzzle is much smaller than initially gleaned. In yet to be published work, Ariell Zimran (see here and here) argues that the antebellum puzzle is robust to the problem of selection bias but that it is indeed diminished. This concedes a large share of the argument to Bodenhorn et al. While there is much to resolve, this article should be read as it constitutes one of the most serious contributions to the field of economic history published in 2017.

Ridolfi, Leonardo. “The French economy in the longue durée: a study on real wages, working days and economic performance from Louis IX to the Revolution (1250–1789).” European Review of Economic History 21, no. 4 (2017): 437-438.

I discussed Leonardo’s work elsewhere on this blog before. However, I must do it again. The article mentioned here is the dissertation summary that resulted from Leonardo being a finalist to the best dissertation award granted by the EHES (full dissertation here). As such, it is not exactly the “best article” published in 2017. Nevertheless, it makes the list because of the possibilities that Leonardo’s work have unlocked.

When we discuss the origins of the British Industrial Revolution, the implicit question lurking not far away is “Why Did It Not Happen in France?”. The problem with that question is that the data available for France (see notably my forthcoming work in the Journal of Interdisciplinary History) is in no way comparable with what exists for Britain (which does not mean that the British data is of great quality as Judy Stephenson and Jane Humphries would point out). Most estimates of the French economy pre-1790 were either conjectural or required a wide array of theoretical considerations to arrive at a deductive portrait of the situation (see notably the excellent work of Phil Hoffman). As such, comparisons in order to tease out improvements to our understanding of the industrial revolution are hard to accomplish.

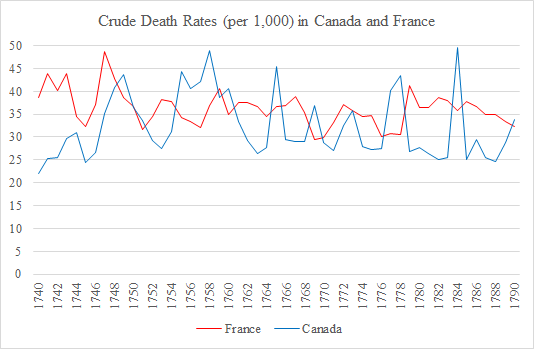

For me, the absence of rich data for France was particularly infuriating. One of my main argument is that the key to explaining divergence within the Americas (from the colonial period onwards) resides not in the British or Spanish Empires but in the variation that the French Empire and its colonies provide. After all, the French colony of Quebec had a lot in common geographically with New England but the institutional differences were nearly as wide as those between New England and the Spanish colonies in Latin America. As such, as I spent years assembling data for Canada to document living standards in order to eventually lay down the grounds to test the role of institutions, I was infuriated that I could do so little to compare with France. Little did I know that while I was doing my own work, Leonardo was plugging this massive hole in our knowledge.

Leonardo shows that while living standards in France increased from 1550 onward, the level was far below the ones found in other European countries. He also showed that real wages stagnated in France which means that the only reason behind increased incomes was a longer work year. This work has also unlocked numerous other possibilities. For example, it will be possible to extend to France the work of Nicolini and Crafts and Mills regarding the existence of Malthusian pressures. This is probably one of the greatest contribution of the decade to the field of economic history because it simply went through the dirty work of assembling data to plug what I think is the biggest hole in the field of economic history.