- International arbitration, 17th century style Eric Schliesser, Digressions & Impressions

- We are no longer a serious people Antonio Martínez, Pull Request

- Networked planetary governance Anne-Marie Slaughter (interview), Noema

- 5 O’Clockface Sharon Olds, Threepenny Review

Nightcap

- Why Angela Merkel has lasted so long Wolfgang Streeck, spiked!

- United States of Greater Austria Wikipedia

- Afghanistan and liberal hegemony Lawrence Freedman, New Statesman

- Diary of the guy who drove the Trojan Horse back from Troy James Folta, New Yorker

Nightcap

- Afghanistan has too much sovereignty Fernando Teson, RCL

- Pakistan’s masochistic support for the Taliban Kunwar Shahid, Spectator

- Has capitalism run out of steam? Dominique Routhier, LARB

- Here come the robot nurses Anna Guevarra, Boston Review

Nightcap

- Is Norway the new East India Company? Branko Milanovic, globalinequality

- A garden tree Eric Schliesser, Digressions & Impressions

- Indian migration and empire Bridget Anderson, Disorder of Things

- A “conservative” case for reparations Jacques Delacroix, NOL

Nightcap

- All-inclusive magic mushroom retreats Max Berlinger, Bloomberg

- What it is to be “young” or “youthful” Eric Schliesser, Digressions & Impressions

- Indian migration and empire Luke de Noronha, Disorder of Things

- Why not rectify past injustices? Bryan Caplan, EconLog

Nightcap

- Why is there no Rooseveltian school of foreign policy? Deudney & Ikenberry, Foreign Policy

- It’s time to drop the curtain on Japan’s colonial legacy Meindert Boersma, Lausan

- The ides of August (Afghanistan) Sarah Chayes (h/t Mark from Placerville)

- Rep. Barbara Lee on Afghanistan, 20 years later Abigail Tracy, Vanity Fair

Nightcap

- Property rights imply social liability, not privilege Rosolino Candela, EconLog

- The lingering scars of World War I Cal Flyn, Atlas Obscura

- Is the Arctic turning blue? (hawkish) Sonoko Kuhara, Diplomat

- Myanmar (or is it Burma?) Zachary Abuza, War on the Rocks

Nightcap

- Placing the American secession in global perspective Steven Pincus, Age of Revolutions

- Trotsky after Kolakowski Branko Milanovic, globalinequality

- A guide to finding faith Ross Douthat, New York Times

- Cancel culture: A recantation Irfan Khawaja, Policy of Truth

Nightcap

- Art and exile in the Third Republic Hannah Stamler, the Nation

- Spending on infrastructure doesn’t always end well Richard White, Conversation

- Kabul and Chicago NEO, Nebraska Energy Observer

- The price of Tucker Carlson’s soul Andrew Sullivan, Weekly Dish

Nightcap

- A fourth globalization Marc Levinson, Aeon

- The Brazilianization of the world Alex Hochuli, American Affairs

- On American foreign policy Eric Schliesser, Digressions & Impressions

- Whither sovereignty Scott Sumner, EconLog

Some Monday links

I didn’t see a draft by Michalis this week, so I thought I’d jump in and substitute. I hope is well with everybody.

History in the Breaking and Making of India

I have argued elsewhere that Republic of India is a Civilization-State, where Indic civilizational features will find increasing expression as the Indian state evolves away from its legacy of the British Raj. However, India’s history is an area of immense concern and a rate-limiting step in the evolution of the Civilization-State. The past seventy-five years of Indian independence have shown that to break away from the influences of intellectual and cultural imperialism is far more complicated than to draw away from political servitude because the foundation of colonization is cultural and spiritual illiteracy.

Colonization influences Indians in unusual ways as it alienates us from our past. For instance, we refer to our Indic formals as ‘ethnic wear’ whereas a suit and a conservative tie in the heat of tropical India is our ‘natural’ formals. The Constitution of India is written in English when only 0.1% of independent India spoke the language. Likewise, the knowledge about India among the English educated elite is generated with an alienating European view when India was colonized. The main interest of the British was to write a history of India that justified their presence. So, they had to acknowledge the legitimacy of preceding violators like the Turks, Persians, and Mongols while accentuating only those Indic kings who either reformed or renounced the Hindu way of life. Several generations of Indians, including me, have grown up studying Indian history textbooks that scarcely evaluate our impact on the outside world even as we painstakingly document the aftermaths of ideas and actions of the outside world on us.

Elites from colonized societies educated in the wake of the colonial rule often standardize colonial scholarship and legitimize it to the extent of rejecting most native insights about their own land, society, and culture. This dynamic largely explains the bloated investment in defining highly racialized tribes and ethnic types in colonized countries. Consider the state of African studies—with a nauseating inflection of Marxist narrative—is affected by similar categories: static tribes, decadent villages, and clashing ethnic groups. These frameworks were essential narratives that justified foreign rule— devices of hierarchical control by colonizing powers. Professor of African and world history Trevor Getz warns us, “the story we often tell of African tribes, chiefs, and villages tells us more about how Europeans thought of themselves in the period of colonization than of the realities in Africa before they came.”

The same holds for the history of Indic civilization. On the threshold of intellectual and cultural decolonization in 1947, when rehabilitating Indic wisdom traditions and the dignity of Hindu civilization was the need of the hour, newly independent India saw the emergence of a new movement in writing its history. Though more self-reliant than Europeans in broadening the scope of Indian social and economic history, this movement deeply dyed Indian history in an expression of Marxism. India’s ancient past became a theater to assert European society’s preconceived class and material conceptions while obliterating the importance of Indic ideas in defining its own historical events. India’s first prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, the Cambridge graduate whose fascination with Marxism and Fabian Socialism had made him an outlandish mix of the East and West, victimized the Indian civilization with his neither here nor their disposition.

Commenting on the sly attempt at thought-control and brainwashing of future generations of newly independent India through a European/Marxist view of Indian history, celebrated Indic thought leader Ram Swarup writes: “Karl Marx was exclusively European in his orientation. He treated all Asia and Africa as an appendage of the West and, indeed, of Anglo-Saxon Great Britain. He borrowed all his theses on India from British rulers and fully subscribed to them. With them, he believes that Indian society has no history at all, at least no known history —implying our history is just a bunch of ancient myths—and that what we call its history is the history of successive intruders. With them, he also believes that India has neither known nor cared for self-rule. He says that the question is not whether the English had a right to conquer India, but whether we are to prefer India conquered by the Turks, by the Persians, to India conquered by the Britons. His own choice was clear.”

As a result of such Marxist scribes, the brutal history of repeated invasions and the forced proselytization of Indic people is described in charitable words, often as the harbinger of an idealized syncretic culture that “refined” the Hindu society. Though I understand the emergence of syncretic cultures, it is absurd for anglicized elites to use them as an all-weather secular rationalization of blatant cultural and intellectual subjugation the Hindu psyche still confronts. The iconoclasm practiced by invading hordes and the resulting ruins of some of the most sacred Hindu sites find no place in our history books because it would ‘communalize’ history. Any inquisitive young Hindu will have to go out of the way to read the works of the trail-blazing Hindu publisher and historian Sita Ram Goel to understand the omitted sections from our history books. His two-volume work titled Hindu Temples, What Happened to Them analyzes nearly two thousand Hindu and Jain temples destroyed by Turkic/Mongol occupiers and their repercussions on the Indic ecosystem.

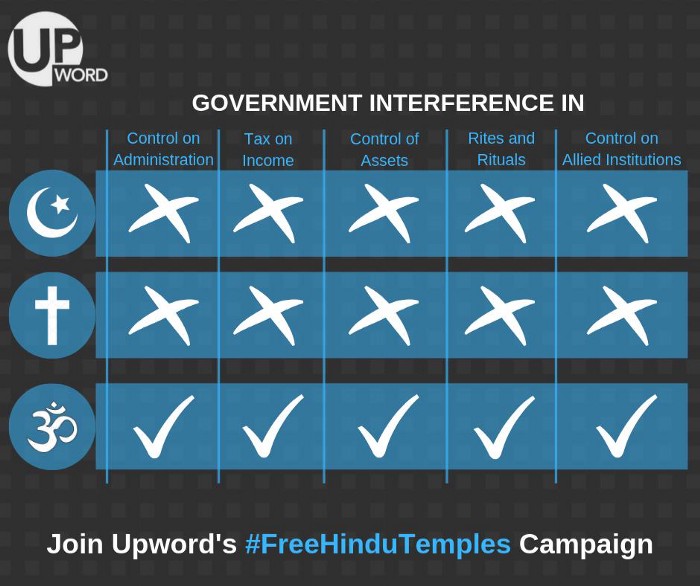

In a bizarre continuation of subjugating the Hindu temple ecosystem, the “secular” Indian state in 1951 under the Indian National Congress and its ideological Marxist and Communist allies selectively usurped Hindu temples and its lands to bring them under state control, and they continue to stifle the temple ecosystem of India. Every non-Hindu has a say on how Hindu temple rituals should be modified but a Hindu talking about Abrahamic practices will amount to a transgression of secularism and religious bigotry. I urge you to watch a quick primer on the crisis of Hindu temples in India — https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=js936p_cvTE.

As though the mainstream Marxist narrative of Indian history wasn’t enough, they have even captured the space of alternative history. Professor Vamsee Juluri, in his book, Rearming Hinduism, compares the dominant and alternative History of India. Here, I present an excerpt from his work:

Mainstream Indian history, as we learned it in school (India):

-Indian history begins with the Indus Valley Civilization (which is not Hindu)

-Hinduism begins with the Aryan Invasion bringing Vedic Religion of Sacrifice

-Hinduism is full of violent animal sacrifice until Buddhism reforms it

-There is a brief Golden Age for Hinduism in which art and culture ‘flourishes,’ and the epic poems, The Ramayana and Mahabharata are composed.

-There are Islamic invasions, but the Mughals bring harmony under Akbar

-The British colonize India; Hinduism is once again reformed

-Gandhi and Nehru free us.

Mainstream history, as it is taught in American schools, from a California textbook:

-Indian history begins with the Indus Valley Civilization (which is not Hindu)

-Hinduism begins with the Aryan Invasion bringing Vedic Religion of Sacrifice

-Hinduism is full of violent animal sacrifice until Buddhism reforms it

-The Ramayana and Mahabharata are composed. They have talking monkeys and bears and Hindus primitively animal-worship them. They also have the holiest text of Hindus, the Gita, which tells Hindus to do their caste duty and war.

The outline of the ‘alternative’ history proposed in Wendy Doniger’s book:

-The Indus Valley Civilization (is not Hindu)

-Hinduism begins with the Nazi-like Aryans bringing Vedic Religion of Sacrifice.

-Hinduism is full of violent animal sacrifice until Buddhism reforms it.

-There is no real Golden Age for Hinduism, but the Greek Invasion leads to great ideas and works of fiction like The Ramayana and Mahabharata. Greek women presumably inspired the fierce and independent Draupadi.

-After chapters called ‘Sacrifice in the Vedas’ and ‘Violence in The Mahabharata,’ at long last, we have ‘Dialogue and Tolerance under the Mughals.’

-The British colonize India; Hinduism is reformed.

-Once India gained independence, without those civilizing external forces, the Hindus became Hindutva extremists.

How can Doniger’s work be an ‘alternative,’ Vamsee Juluri asks, when its claims are the same as the dominant narrative? He notes that this ‘alternative’ history of Hinduism is at the top of the heap in most bookstores in the West, and its thesis dominates the press coverage of Hindu India. In a normal world, if there were ten titles written by ‘Hindu apologists’ on the shelf, then an ‘alternative’ would have indeed been worthy of the respect that term brings. Hence, the mainstream and the so-called alternative narratives of Indian history are both contemptuous for India of Hindu religion, culture, and philosophy. It is fortified in the republic of letters as ‘progressive’ criticism. This narrative still holds sway over academic appointments, research grants, crafting syllabi, and promoting textbooks. In other words, postcolonial Indian historians have primarily pursued the same blinkered colonizing vision of their masters who saw history only through a narrow prism of class, material wealth, and outsiders descending upon Hindus to ‘reform’ our heathen culture. In contrast, the history of the Hindu past is framed strictly within the confines of a region or sectarian terms. Therefore, instead of seeing the invaders for who they were, the history of Hindu India provincializes itself in this process and legitimizes self-hatred.

With a deep concern for such self-hatred in historical narratives, the Nobel Laureate V. S. Naipaul said: “This inveterate hatred of one’s ancestors and the culture into which they were born is accompanied by a hatred deep enough to want to destroy one’s own land and join the ranks of the violators of the ancestral land and culture, at least in spirit. Pakistan is an example. Its heroes are not the Vedic kings and Indic sages who walked the land but invading vandals like Ghaznavi and Ghori, who ravaged them.”

Accounting for the history of any country is a delicate task. However, it is far more sensitive for a civilization that has had a long colonial past. So, while reading mainstream Indian history, one must be mindful of what the foreigners wanted to know first. Because what they wanted to perceive foremost was beneficial to them in ruling the place as handily as possible, which effectively explains the dominance of hollow postulates surrounding racialized ethnic Aryan and Dravidian divides, and confounding European class concept with Hindu Varna in colonial and Marxist literature. These factors make it practically impossible for modern observers not to visualize previously colonized societies as changeless and unevolved for centuries. They never question if Indic social features are also aftermaths of several invading powers, the resulting conflict, and instinctive adaptations. Entities like factions and castes are often not static social constructs that result from endlessly contested histories. In Indic civilization and other colonized lands, such identities were often situational and flexible, not wholly rigid, and all-encompassing; wholesale rigidity is often a bug that needs exploration and explanation, not a feature to be endorsed unquestioned. A.M.Hocart, regarded by the philosopher-traditionalist Ananda Coomaraswamy as perhaps the only unprejudiced European sociologist who has written on caste, states: “It is at present fashionable to rationalize all customs, and to write up the “economic man” to the exclusion of that far older and more widespread type, the religious man, who, though he tilled and built and reared a family, believed that he could do these things successfully only so long as he played his allotted part in the ritual activities of his community.”

Indeed, the rigidity of the caste system was not the cause but the effect of the breakdown of political order. Moreover, the fixation with caste in Indian historical writings has made us oblivious to the profound ontological assumptions underlying the complexities of Indian society. Hindu society conceived multidirectional relationships at different levels of existence. This ideal of the individual-community relationship assumed that although human beings differ in temperament, each of them must try to develop and realize the full potential of being human through seeking greater intercourse with other members as part of cosmic reality. Dumont misunderstands this notion and argues that the individual in Indian thought did not exist beyond the idea of caste. It is simply not true because the concept of Indic autonomy is different from Individualism. Rights in Western liberal traditions are ‘claims’ against others in the society, but Indic society gave prominence to duties first, as it presupposed the consideration of others without obliterating autonomy. According to treatises like Sukraniti and the grand wisdom of Atharvaveda, autonomy is the state when no one can dominate us against our will or fundamental nature. Indian thought refers to this state as Swaraj; the Indian struggle for independence was predicated on Swaraj.

Several other Indic scholars have highlighted the adverse effect of excessive emphasis on caste coupled with a de-emphasis of equally important other Indic social concepts. Factors such as ashrama, shreni, Kula and Jati, and above all Dharma (Global Ethic) are overlooked, leading to a grave misunderstanding about the character of Hindu society through its historical writings. Indeed, in the Ramayana (venerated Indian epic-poem composed by an author not belonging to the “upper class”) and Mahabharata (revered Indian epic-poem composed by an author born to a fisherwoman) and in the broad scope of Puranic literature, there is a notion of an individual who gives life and substance to the existence in this world. Indeed, so great has been the weight attached to the individual that Indic art and literature are sought to be expressed through the lives of such individuals, be it limited but the exuberant personality of Sri Rama or the unlimited personality of Sri Krishna (a cowherd who is the ultimate avatar; he also happens to be dark-complexioned) or the non-dimensional, half-man half-woman personality of Shiva. Needless to add that the importance of the themes discussed here springs from the fact that Hindu society of 2021 is still largely organized around them.

Indic pantheism may look absurd to atheists and those of Abrahamic persuasion alike. Nevertheless, the Indic tradition has always had a transnational characteristic and considerable geopolitical sphere of influence. Therefore, in the future Hindu scholarship will understandably reject the notion of the colonial or Marxist intelligentsia that overemphasized the ‘local’ or ‘regional’ as more ‘authentic’ than the larger society, territory, or neighborhood of the Hindus. Hindu scholars of today already investigate more into the interplay of local, regional, national, and global settings that have historically responded to Hindu thought and actions. As native scholarship course corrects Indian history, the updated Indian history textbooks of the future will undoubtedly give way to a bad press in the global north with alarmist headlines such as ‘Hindu revision of Indian history.’ Still, anyone with a reasonable amount of grey matter needs to recognize the mobility of Hindu predecessors and think through the different spatial frameworks they occupied and traversed Bhārata (the original name of Indic Civilization mentioned in the Indian constitution).

When external forces become overpowering, or the body of society is unable to assimilate them, inevitable tensions are generated, leading to its decay. The interaction of the outside influences with the total personality of the Hindu society and various traditions within it can be a fascinating study. I’m not suggesting that the mainstream discourse has no valuable insights in this regard. I’m only pointing at the enormous biases and gaps and how native Hindu scholarship is best equipped to address them. As I see it, an inevitable manifestation of cultural and intellectual decolonization of the Indian Civilization-State is the progressive recognition of the depth and scope of its Hindu character. A character that remains currently truncated for ‘communal’ comfort in the dominant narrative of Indian history.

Some Monday Links

Symposium: Washington Consensus Revisited (Journal of Economic Perspectives)

Three Days at Camp David: The Fiftieth Anniversary (The International Economy)

Friends, Romans, Countrymen (Lapham’s Quarterly)

Biden’s newest foreign policy challenge: Iranian and Israeli hardliners

Introduction

After the triumph of Ebrahim Raisi in the June 2021 Iranian Presidential election, the US and other countries, especially the E3 (the UK, Germany, and France), which are party to the JCPOA/Iran Nuclear deal would have paid close attention to his statements, which had a clear anti-West slant. Raisi has made it unequivocally clear that while he is not opposed to the deal per se, he will not accept any diktats from the West with regard to Iran’s nuclear program or its foreign policy in the Middle East.

In addition to Raisi’s more stridently anti-US stance, at least in public, what is likely to make negotiations between Iran and the US tougher is the recent attack on an oil tanker, off Oman, operated by Zodiac Maritime, a London based company owned by an Israeli shipping magnate, Eyal Ofer. Israeli Foreign Minister Yair Lapid did not take long blame Iran for the attack, referring to this as an example of ‘Iranian terrorism’ (current Israeli PM Naftali Bennett’s policy vis-à-vis Iran is no different from that of his predecessor Benjamin Netanyahu). After Raisi’s win in June, Israel had reiterated its opposition to negotiating with Iran, and the Israeli PM termed the election of hardliner Raisi as a ‘wake up call’ for the rest of the world. Two crew members — a Romanian and a Briton, were killed in the attack.

While the Vienna negotiations between Iran and other signatories to JCPOA (the US is participating indirectly) have made significant progress, Raisi could ask for them to start afresh, in which case the US has said that it may be compelled to take strong economic measures, such as imposing sanctions on companies facilitating China’s oil imports from Iran (ever since the Biden administration has taken over there has been a jump in China’s oil purchases from Iran).

It would be pertinent to point out that pressure from pro-Israel lobbies in the US, as well as apprehensions of Israelis themselves with regard to the JCPOA, were cited as one of the reasons for the Trump administration’s maximum pressure policy vis-à-vis Iran, as well as the Biden administration’s inability to clinch an agreement with the Hassan Rouhani administration. While at one stage the Biden administration seemed to be willing to get on board the JCPOA unconditionally, it is not just domestic pressures, but also the fervent opposition of Israel to the JCPOA which has acted as a major impediment. While GCC countries Saudi Arabia and UAE were fervently opposed to the JCPOA and also influenced the Trump administration’s aggressive Iran policy, in recent months they have been working towards improving ties with Iran, and have softened their stance.

Washington should refrain from taking any harsh economic steps

At a time when the Iranian economy is in doldrums (the currency has depreciated and inflation has risen as a result of the imposition of sanctions and of Covid-19), Washington would not want to take any steps which result in further exacerbating the anti-US feeling in Iran. While commenting on the attack on the Israeli managed tanker, US Secretary of State Anthony Blinken said:

We are working with our partners to consider our next steps and consulting with governments inside the region and beyond on an appropriate response, which will be forthcoming

There is no doubt that the maximum pressure policy of the Trump administration of imposing harsh sanctions on Iran did not really benefit the US, and Joe Biden during the presidential campaign had been critical of the same. Reduction of tensions with Iran is also important given the current situation in Afghanistan, and Tehran’s importance given its clout vis-à-vis the Taliban.

US allies and their role

US allies themselves are looking forward to the revival of the JCPOA, so that they can revive economic relations with Iran. This includes the E3 (Germany, the UK, and France) and India. As mentioned earlier, GCC countries like Saudi Arabia and UAE, which in recent years have had strained ties with Iran, are seeking to re-work their relations with Tehran as a result of the changing geopolitical environment in the Middle East.

The role of US allies who have a good relationship with both Israel and Iran is important in calming down tempers, and ensuring that negotiations for revival of JCPOA are not stalled.

Conclusion

It is important for Biden to draw lessons from Trump’s aggressive Iran policy. Biden should not allow Israel or any other country to dictate its policy vis-à-vis Iran, as this will not only have an impact on bilateral relations but have broader geopolitical ramifications. Any harsh economic measures vis-à-vis Iran will push Tehran closer to China, while a pragmatic policy vis-à-vis Tehran may open the space for back channel negotiations.

Raisi on his part needs to be flexible and realize that the most significant challenge for Tehran is the current state of its economy. Removal of US sanctions will benefit the Iranian economy in numerous ways but for this he will need to be pragmatic and not play to any gallery.

Police Killings and Race: Afterthoughts

The verdict on former officer Chauvin seems extreme to me. I think manslaughter would have been enough. Of course, it’s possible that I don’t understand the legal subtleties. Also, I did not receive all the information the jurors had access to. Also, I didn’t have to make up my mind under the pressure of fearing to trigger a riot in my own city.

As usual, I react to what did not happen. In the sad Floyd case, a bell weather for a new anti-racist movement in the US, the prosecution did not allege anything of a racial nature. Let me say this again: for some reason, the prosecutor did not claim that the victim’s race played a part in his death. Strange abstention because such a claim would have almost automatically brought to bear the enormous weight and power of the Federal Government. (The Feds are explicitly in charge of dealing with suspected violations of civil rights.)

Personally, I think we have a general problem of police brutality in this country. I mean that American cops are entirely too prompt to shoot. I also believe this is largely a result of permissive training on the matter. American police doctrine gives cops too much leeway about when to shoot a suspect. It does not do enough to support alternatives, including less than lethal means of incapacitation. Here is a small piece of supporting evidence: An American is about ten times more likely to be killed by the police than a French person. One can try to claim that French criminals and French suspects are ten times less dangerous than their American counterparts. Read this aloud and think it through. (Of course, there is always the possibility that your average French suspect, with his funny beret and a baguette tucked under his arm, is in a bad position to shoot at police at all.)

As for the widespread claim that American police killings of civilians are racially motivated, a proof of racism- systemic or otherwise – this case has simply not been made. Here are a handful of relevant numbers: In the USA, a black person interacting with the police has no greater chance of being killed than a white person. A black person interacting with a black police officer has the same chance of being killed as one interacting with a white officer. It’s true that a black person, on the average is more likely to be interacting with police than a white person. If racism plays a role in the killing of black people by police, that is where it is lodged. Police, white and black, are more likely to stop blacks than whites. Can you guess any reason why? Can the reason be other than racism? Below is a link to a wider essay on the topic:

Systemic Racism: a Rationalist Take