- How did the West get religious freedom? Mark Koyama, Defining Ideas

- Are asylum rights misguided? Tyler Cowen, Marginal Revolution

- What Does China’s 5th Research Station Mean for Antarctic Governance? Nengye Liu, the Diplomat

- The forthcoming changes in capitalism? Branko Milanovic, globalinequality

Nightcap

- Privilege Versus Paranoia Steve Salerno, Quillette

- Russia, sport, absurdity, and reality Arkady Ostrovsky, Times Literary Supplement

- Christian Zionism in America Steven Grosby, Law & Liberty

- Welcome to North Macedonia Michael Goodyear, Le Monde Diplomatique

Nightcap

- Trump’s ‘Great Chemistry’ With Murderous Strongmen Conor Friedersdorf, the Atlantic

- A Little-Noticed Legal Ruling That Is Bad News for Trump Damon Root, Volokh Conspiracy

- Will the Pause in South Asian Conflicts Last? Arif Rafiq, the National Interest

- The changing shape of Britain’s mosques Burhan Wazir, New Statesman

Nightcap

- Gaza is bad. We are about to make it worse Michael Koplow, Ottomans and Zionists

- Jews, Human Rights, and the Last of the Tzaddiks David Shulman, NY Review of Books

- The Liberal Conception of Freedom Nick Nielsen, The View from Oregon

- The 19th-century painter with a warning for America Julian Beecroft, 1843

Nightcap

- Is fasting good for you? S. Abbas Raza, Aeon

- French Catholicism: A Eulogy Rod Dreher, American Conservative

- Iran’s (literary) sexual revolution Pardis Mahdavi, Times Literary Supplement

- How Trump is reshaping American foreign policy Paul Pillar, National Interest

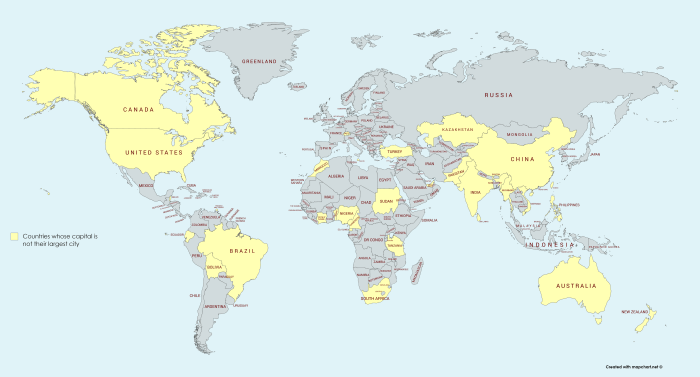

Eye Candy: Countries whose capital is not their largest city

Not much to add here. There doesn’t seem to be any correlation of any kind (colonialism, economic development, etc.). Still, I thought it was cool…

Nightcap

- Siberia: a (concise) history Rhys Griffiths, History Today

- SPLC vs Maajid Nawaz: we should be concerned Ken White, Popehat

- Why women don’t code Stuart Reges, Quillette

- Benedict Arnold wanted a life of distinction Rick Brownell, Historiat

Nightcap

- The example of Charles Krauthammer Henry Farrell, Crooked Timber

- Turkey tries to legitimize incursion in northern Iraq Adnan Abu Zeed, Al-Monitor

- Why America won’t declare war Matthew Fay, Niskanen Center

- Stare Decisis and judge-made law Will Baude, Volokh Conspiracy

Nightcap

- Parents are heroes Rachel Lu, the Week

- Echoes of Reagan in Trump’s Clashes With Allies Ira Stoll, Reason

- Trump should pardon Obama-era whistle blower Bruce Fein, the American Conservative

- (Natural) Historical Haircuts Jonathan Saha, Colonizing Animals

Debating a Marxist: An invitation

This week, I thought it might be fun to take a break from the series on the state and education and instead to introduce the topic of up-close and personal encounters with some very interesting people: Marxists. My reason for writing on this topic is simply that I’m curious to see if other people have had similar experiences and what the Notes on Liberty community thinks of this breed.

In my experience, there are two archetypes of modern Marxist. The first is the “cultural” one. This one is to my mind the more preferable of the two. This one conscientiously reads all the literature associated with Marxism and its derivatives, normally discards much of the economic aspects, and embraces the social and intellectual pieces. They tend to not think too highly of The Communist Manifesto but are crazy about Marx’s The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Napoléon. The result is that they cerebrally focus on class struggle, disenfranchisement, social inequality, etc., all while happily stipulating to all of the horrible famines, massacres, breadlines, general deprivation, etc. that occurred under Marxism. Their attitude is similar to a person who uses an old, long unpracticed religion as a form of social identification, e.g. “I’m Catholic (though I haven’t been to Mass in 40 years and support causes frowned upon by the Church).”

The standard response when asked about the fruits of Marxism tends to be a variant of “That wasn’t true Marxism; Marxism done right wouldn’t have caused that,” or “it just wasn’t implemented properly.” I have even heard one along the lines of “That was communism, not Marxism.” The cultural Marxist is easy to get along with. Because he tends to be a genuine intellectual and honest academic, when faced with reputable sources, he will graciously concede the point. Since this type respects skill and knowledge, there is a shared framework in which to debate. He is happy to debate anything and never views any author or source as particularly sacrosanct.

As a result, the cultural Marxist is reasonably open-minded and eager to find some common ground. My personal encounters with this type tend to be positive and normally end with everyone buying everyone else coffee and leaving the meeting as friends. They also tend to be pragmatic; during my time at Columbia (it’s reputation should be well known vis-à-vis Marxism), there was one faculty member who could only be described as fiscally capitalist and socially Marxist. Dovetailing with debates on class structure, we also received exhortations to secure our financial futures and received step-by-step instructions on how to invest in Vanguard mutual funds! It was slightly surreal, but I later discovered that this hybrid attitude is fairly typical among cultural Marxists. For them, it’s not about the money; it’s about the ideas. But because they mix and match ideas to create a personal worldview, they are neither invested in any particular aspect of Marxism, nor overly interested in practicing it.

The other archetype is the rabid ideologue who believes everything from Karl Marx, Vladimir Lenin, and, variably, Ivan Trotsky, Josef Stalin, or Mao Tse-tung is gospel. Unlike the cultural Marxist, the knowledge of ideologue tends to be constrained to a limited number of sources and works. The existence of The Eighteenth Brumaire can come as a surprise to these people, though they can quote The Communist Manifesto practically verbatim. Encounters with this type disintegrate to name calling and ad hominem attacks within a matter of minutes, in my case usually when their source foundations have been abolished in debate. The hallmark of their mentality is a fixed belief that if they personally are incapable of something, then no one else can do it either.

As an example, a group of students, including myself, went to a performance of La Traviata at Opéra Bastille in Paris. One of our number turned out to be a Marxist ideologue who spent the evening denigrating the entire affair. I recall one particularly embarrassing moment during an intermission when the person loudly ranted about how none of the attendees were there through love of music, being only drawn through an affected desire to show off and appear cultured. All attempts to inveigle the person to return quietly to our seats failed. Never once did it occur to the person to observe that evidence of genuine music appreciation was present just within the student group.

Recently, I tangled with a self-identified Marxist-Leninist ideologue online. Somehow the conversation careened from the original topic to his insistence that I couldn’t possibly have functional fluency in six languages (classical musicians have to be able to read and work in the five languages of music – English, French, German, Italian, and Latin – and I studied Ancient Greek through college). The only justification for his doubts appeared to be that he only had knowledge of three languages. The pivot and then ad hominem doubt is all par for the course in dealing with this type of person, but what struck me is that in all my history of engagements only ideologue Marxists have used the “you can’t possibly be or do X because I’m not or can’t” argument. This is where there is a real divergence between ideologue Marxists and cultural Marxists: all of the latter I have interacted with are highly capable people who go to the opposite extreme and assume that others are informed and thoughtful as well. On a side note, there is nothing quite as entertaining as watching a cultural Marxist debate an ideologue; it inevitably ends with a scorched earth defeat of the ideologue.

Since all of these interactions are anecdotal, they may be sheer personal experience and could very well be due to ideological ignorance. At this point, I invite members of the NOL community to relate their personal stories of brushes with Marxists and what most struck them about their mentality and approach. What is the most irrational thing you have heard on this topic? Were you able to reach a state of détente? Did the discussion end in a draw, or a meltdown? Are there any archetypes you might add?

Notā bene: I am entering an intensive language course in preparation for doctoral studies. As a result, I may not be very present on NOL for the summer. I will do my best, though, to monitor comments and to be part of the conversation.

Nightcap

- The man who went to the North Korean place that ‘doesn’t exist’ Megha Mohan, BBC

- Assessing Our Frayed Society with (German-Korean philosopher) Byung-Chul Han Scott Beauchamp, Law & Liberty

- Baxter Street & Jury Duty, Summer of 2016 Edward Miller, Coldnoon

- Ta-Nehisi Coates & the Afro-Pessimist Temptation Darryl Pinckney, New York Review of Books

Red Lobsters and Black Swans

Back In 2007 Nassim Nicholas Taleb had estimated that, in the following years, the rate of irruption of highly improbable events that change our way to perceive reality would be on the increase. Using his terminology, we would swiftly drift from Mediocristan out to Extremistan. People would have to deal with black swans more often and adapt to the new scenario.

The sudden spreading of Jordan Peterson’s lobsters might be a confirmation of Taleb’s surmise (in Extremistan, the term “surmise” has not any derogatory connotation). “Stand up straight with your shoulders back” is a piece of advice aimed at people who feel overwhelmed by a state of affairs, both personal and public, whose complexity they can hardly grasp. In Taleb’s terms, Jordan Peterson wants to prepare you for a world in which the Black Swans are the underlying reality.

Our quantitative patterns about reality -both physical and social- contribute to preserve fixed relationships among the terms that build up our world and subjectivity -while every now and then the “untimely” burst into our sense of reality. The Nietzschean “untimely” had always been there, out of the reach of our horizon of perception, but ready to appear suddenly and unexpectedly, like the plague in Thebes.

Nevertheless, perhaps there is no underlying chaotic reality, but a Hofstadter’s braid, where Apollo and Dionysus are intertwined: simple and complex phenomena, back to back, the beauty and the sublime. Upon one side, the train of events represented by a correlative train of thoughts; on the reverse, a plane of unarticulated notions that are inherent to those representations.

In this sense, the matrix of Taleb’s Black Swans might not inhabit the undertow of our perceptions, but stand above them, in a plane of a higher degree of complexity. Each new event triggers our brain to readjust our system of classifications. But this readjustment, at its time, triggers off a reconfiguration in the said plane of unarticulated notions that give support to our set of representations. In principle, an arrangement of such events would remain stable, but sometimes some unintended consequences could arise. That is the dynamic of events that Friedrich Hayek had once tried to convey with his concept of spontaneous or abstract order.

Peterson’s Red Lobsters try to make us reflect on the edge of our common patterns of conduct, whereas Taleb’s Black Swans incite us to perform the speculative activity of throwing hypothesis over the singularity of the abstract order, so that to anticipate any unintended consequences of our individual or collective behaviour. Notwithstanding the huge differences that there might be between them, what deserves our main attention is the acknowledgement of that the unplanned, the unexpected, the uncertain, are not alien forces, but the inherent articulation of the patterns of events that constitute the matter we are face to deal with.

Nightcap

- Why a State typically promotes its own official language Pierre Lemieux, EconLog

- Foreign languages and self-delusion in America Jacques Delacroix, NOL

- Islam’s new ‘Native Informants’ Nesrine Malik, NY Review of Books

- The khipu code: the knotty mystery of the Inkas’ 3D records Manuel Medrano, Aeon

Separation of Children: an American Tradition

Many Americans deplore the forced separation of children from their parents when they attempt an unauthorized entry into the USA. The recorded crying of children traumatized from having their parents taken away is terrible to hear for anyone with empathy. Administrations excuse this by claiming that they are only enforcing a legally mandated zero tolerance, that this separation acts as a useful deterrent to immigration, and that the law is ordained by God.

The claim by those opposing this policy is that this cruel separation is un-American. But in fact, the forced separation of children is an American tradition. Under slavery prior to the end of the Civil War, children were sold separately from their parents. This action too was presumably a law ordained by God.

The separation of children from their parents was also imposed on native American Indians. Children were forcibly removed from their homes and put into boarding schools, the aim being the assimilation of Indians into Euro-American culture. Indian children were not allowed to speak in their native languages. Rather than being un-American, this physical and cultural separation was seen as an Americanization. Canada had a similar program for its Indians.

This separation continued the genocide of Indians by having a high rate of death. The misery that children felt in their familial and cultural separation was compounded by abusive treatment and a high mortality rate.

Since the current child separation is a continuation of past policies, we can expect similar outcomes: abuse, death, and suicides. Feeling no hope of ever seeing their parents again, confined to small cages, suffering from boredom, and constantly hearing other children crying, there could be substantial illness and even suicide in these detention camps. It would at first be covered up, and then exposed, and denied as “fake news.”

This anti-family policy is supported by many Republicans and conservatives. The conservative claim of supporting “family values” has now been shown to be fake. The real conservative stance is the imposition of traditional European culture and supremacy. Most of the migrants from Central America and Mexico are of native Indian ancestry. When they are rejected and sent back to their home countries to get killed by the violence from which they fled, this is in accord with the American tradition of European racial supremacy over native American Indians. If those seeking to immigrate were Norwegians, those families would not be split up.

Indeed, those subjected to forced family separation were races that were conquered and regarded as inferior. A large immigration from Mexico and Central America would repopulate the USA with native Indian “blood,” unacceptable to Euro-American supremacists.

Therefore the forced separation of native Indians from their parents and the rejection of further immigration is as American as one could get.

RCH: the Cherokee Nation and the US Civil War

That’s the topic of my Tuesday column over at RealClearHistory. An excerpt:

Ross was critical of the success of the death warrants against the Treaty Party Men, but the most interesting aspect of the two mens’ rivalry was the fact that they used the rule of law to fight their battles. Now, the rule of law in the 19th century meant the use of violence between factions (think here about Tombstone, Ariz., where Wyatt Earp and his friends were U.S. Marshals and the friends of the Clantons were Sheriffs), but there was a belief held at the time that violence could only be used by civilized men if the law was on their side. Ross and Watie were both firm believers in this form of rule of law.

Please, read the rest and share it with your friends.