- Can there be peace in Afghanistan? Shreyas Deshmukh, Pragati

- Competition among states wasn’t sufficient for religious liberty Johnson & Koyama, Cato Unbound

- Transnational queenship Michelle Beer, JHIBlog

- Russia the Terrible Timothy Crimmins, Modern Age

From the Comments: who is the conservative or libertarian equivalent of Nancy MacLean?

Rick posed a great question about Nancy MacLean awhile back. I haven’t been neglecting it. I’ve been thinking about it. Here it is:

Question for those more abreast than me: do conservatives or libertarians have an equivalent of Nancy MacLean? All sides have irresponsible pseudo-scholars, but how often do the various camps launch one of them to undue prominence instead of just ignoring them?

Michelangelo suggests Murray Rothbard as one example, and I had that thought as well, but that’s almost too obvious, and he’s been dead for a long time now.

Libertarians today are pretty firmly divided by the cosmos and paleos, so undue prominence is hard to get. When was the last time you saw Jason Brennan or Bryan Caplan praising the work of Justin Raimondo or Lew Rockwell?

With that being said, I think libertarians nowadays tend to launch intellectual fads into undue prominence, rather than scholars. Stuff like Open Borders or signaling or my personal favorite, non-intervention in foreign policy, tend to hold a prominence in libertarian circles that I find ridiculous. If you don’t believe me, find your nearest Cato Institute scholar on Twitter and ask him (yes, him) if his pet policy project has any potential flaws in it…

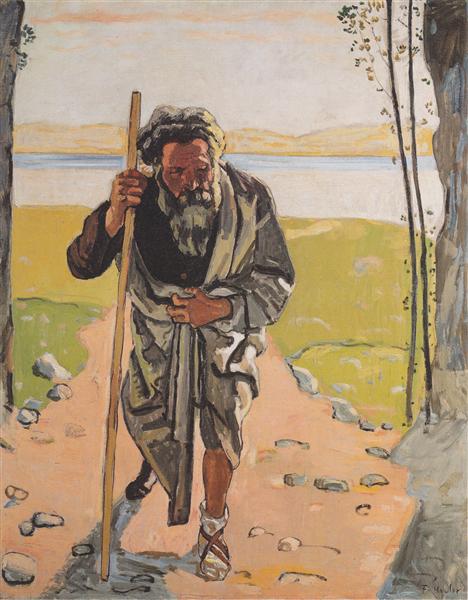

Afternoon Tea: Ahasver (1910)

This beauty is by Ferdinand Hodler, a Swiss painter. Rest assured, there’ll be more from him.

Nightcap

- How to pay for the Green New Deal Simon Wren-Lewis, mainlymacro

- Racism in an elevator Alison Bowles, Policy of Truth

- The fitful march of religious liberty Johnson & Koyama, Cato Unbound

- The why of religious freedom Ethan Blevins, NOL

Nightcap

- Franklin D. Roosevelt Jackson Lears, London Review of Books

- Memoir of captivity in Iran John Tamny, RealClearMarkets

- Towards decentralization Andy Smarick, National Affairs

- Did humans tame themselves? Melvin Konnor, the Atlantic

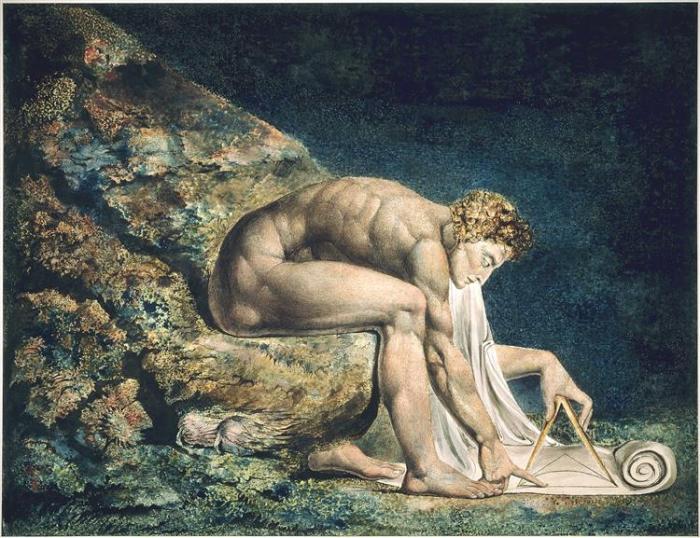

Afternoon Tea: Isaac Newton (1795)

From the British artist and poet William Blake:

I’ve never been a huge fan of English art, but Blake is an obvious exception to the rule when it comes to art out of England. If you expand British art to include its imperial domains, then British art is spectacular, but as for England itself, meh. (William Blake excepted, of course.)

The Paradox of Prediction

In one of famous investor Howard Marks’ memos to clients of Oaktree Capital, the eccentric and successful fund manager hits on an interesting aspect of prediction markets and probability alike. In 1993 Marks wrote:

Being ‘right’ doesn’t lead to superior performance if the consensus forecast is also right. […] Extreme predictions are rarely right, but they’re the ones that make you big money.

In economics, the recent past is often a good indicator for the present: if GDP growth was 3% last quarter, it is likely around 3% the next quarter as well. Similarly, since CPI growth was 2.4% last year and 2.1% the year before, a reasonable forecast for CPI growth for 2019 is north of 2%.

If you forecast extrapolation like this, you’d be right most of the time – but you won’t make any money, neither in betting markets nor financial markets. That is, Marks explains, because the consensus among forecasters are also hoovering around extrapolations from the recent past (give or take some), and so buyers and sellers in these markets price the assets accordingly. We don’t have to go as far as the semi-strong versions of the Efficient Market Hypothesis which claim that the best guesses of all publicly available information is already incorporated into the prices of securities, but the tendency is the same.

- if you forecasted 5% GDP growth when most everyone else forecasted 3%, and the S&P500 increased by say 50% when everyone estimated +5%, you presumably made a lot more money than most through, say, higher S&P500 exposure or insane bullish leverage.

- If you forecasted -5% GDP growth when most everyone else forecasted 3%, and the S&P500 fell 40% when everyone estimated +5%, you presumably made a lot more money than most through staying out out S&P500 entirely (holding cash, bonds or gold etc).

But if you look at all the forecasts over time by people who predicted radically divergent outcomes, you’ll find that they quite frequently predict radically divergent outcomes – and so they would be spectacularly wrong most of the time since extrapolation is usually correct. But occasionally they do get it right. In hammering the point home, Marks says:

the fact that he was right once doesn’t tell you anything. The views of that forecaster would not be of any value to you unless he was right consistently. And nobody is right consistently in making deviant forecasts.

The forecasts that do make you serious money are those that radically deviate from the extrapolated past and/or current consensus. Once in a while – call it shocks, bubble mania or creative destruction – something large happens, and the real world outcomes land pretty far from the consensus predictions. If your forecast led you to act accordingly, and you happened to be right, you stand the make a lot of money:

Predicting future development of markets thus put us in an interesting position: the high-probability forecasts of extrapolated recent past are fairly useless, since they cannot make an investor any money; the low-probability forecasts of radically deviant change can make you money, but there is no way to identify them among the quacks, charlatans, and permabears. Indeed, the kind of people who accurately call radically deviant outcomes are the ones who frequently make such radically deviant projections and whose track record of accurately forecasting the future are therefore close to zero.

Provocatively enough, Marks concludes that forecasting is not valuable, but I think the bigger lesson applies in a wider intellectual sense to everyone claiming to have predicted certain events (market collapses, financial crises etc).

No, you didn’t. You’re a consistently bullish over-optimist, a consistent doomsday sayer, or you got lucky; correctly calling 1 outcome out of 647 attempts is not indicative of your forecasting skills; correctly calling 1 outcome on 1 attempt is called ‘luck’, even if it seems like an impressive feat. Indeed, once we realize that there are literally thousands of people doing that all the time, ex post there will invariably be somebody who *predicted* it.

Stay skeptical.

Originalism and defamation

Today, Justice Clarence Thomas issued a solo opinion urging the Supreme Court to reconsider a hallmark case in First Amendment law–New York Times v. Sullivan. That case held that defamation claims brought by public figures had to meet a heightened standard of proof by showing “actual malice” by the alleged defamer. The basic premise is that muscular use of private defamation suits discourages criticism of public figures and thus clashes with First Amendment interests.

Justice Thomas’s primary complaint with this standard is that judges created it with a wave of the wand rather than a serious analysis of the original understanding of the First Amendment. He points out that the ratifiers of the Constitution gave no indication that they intended to abrogate the long-standing common law of libel that had existed in the colonies and England for centuries. For those who believe that the Constitution’s meaning should reflect what the ratifiers thought the language meant at the time, I think Justice Thomas makes a convincing case.

Nightcap

- Ottoman nostalgia (back to the Balkans) Alev Scott, History Today

- Did post-Marxist theories destroy Communist regimes? Branko Milanovic, globalinequality

- Islam in Eastern Europe (a silver thread) Jacob Mikanowski, Los Angeles Review of Books

- Against Imperial Nostalgia: Or why Empires are Kaka Barry Stocker, NOL

The American objective of isolating Iran continues to be a failure

Recent days have been witness to important events; The Middle East Conference at Warsaw, co-hosted by Poland and the US State Department on February 13 & 14, and the Munich Conference. Differences between the EU and the US over dealing with challenges in the Middle East, as well as Iran, were reiterated during both these events.

The Middle East Conference in Warsaw lacked legitimacy, as a number of important individuals were not present. Some of the notable absentees were the EU Foreign Policy Chief, Federica Mogherini, and the Foreign Ministers of Germany, France, and Italy. Significantly, on February 14, Iranian President Hassan Rouhani, Russian President Vladimir Putin, and Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan met in Sochi, Russia to discuss the latest developments in Syria and how the three countries could work together.

Personalised aspect of Trump’s Diplomacy

In addition to the dissonance between EU and US over handling Iran, the dependence of Trump upon his coterie, as well as personalised diplomacy, was clearly evident. Trump’s son-in-law and Senior Aide, Jared Kushner, spoke about the Middle East peace plan at the Warsaw Conference, and which Trump will make public after elections are held in Israel in April 2019. The fact that Netanyahu may form a coalition with religious right wingers could of course be a major challenge to Trump’s peace plan. But given his style of functioning, and his excessive dependence upon a few members within his team who lack intellectual depth and political acumen, this was but expected.

EU and US differences over Iran

As mentioned earlier, the main highlight of both events was the differences over Iran between the EU and Israel, the US and the GCC (Gulf Cooperation Council) countries. While Israel, the US, and the Arabs seemed to have identified Iran as the main threat, the European Union (EU), while acknowledging the threat emanating from Iran, made it amply clear that it disagreed with the US method of dealing with Iran and was against any sort of sanctions. US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo went to the degree of stating that the goal of stability in the Middle East could only be attained if Iran was ‘confronted’.

The EU differed not just with the argument of Iran being the main threat in the Middle East, but also with regard to the methods to be used to deal with Iran. The EU, unlike the US, is opposed to the US decision to get out of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) and is all for engaging with Iran.

At the Warsaw Conference Vice President Mike Pence criticised European Union member countries for trying to circumvent sanctions which were imposed by the US. Pence was referring to the SPV (Special Purpose Vehicle) launched by Germany, France, and Britain to circumvent US sanctions against Iran. The US Vice President went to the extent of stating that the SPV would not just embolden Iran, but could also have a detrimental impact on US-EU relations.

US National Security Adviser John Bolton has, on earlier occasions, also spoken against the European approach towards the sanctions imposed upon Iran.

Differences at Munich Conference

The differences between the US and the EU over Iran were then visible at the Munich Conference as well. While Angela Merkel disagreed with Washington’s approach to the Nuclear Deal, she agreed on the threat emanating from Iran but was unequivocal about her commitment to the JCPOA. While commenting on the importance of the Nuclear Agreement, the German Chancellor said:

do we help our common cause… of containing the damaging or difficult development of Iran, by withdrawing from the one remaining agreement? Or do we help it more by keeping the small anchor we have in order maybe to exert pressure in other areas?

At the Munich Conference too, the US Vice President clearly flagged Iran as the biggest security threat to the Middle East. Pence accused Iran of ‘fueling conflict’ in Syria and Yemen, and of backing Hezbollah and Hamas.

GCC Countries at the Warsaw Conference

It is not just the US and Israel, but even representatives of the GCC which took a firm stand against Iran. (A video leaked by Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu revealed this.)

Bahraini Foreign Minister Khaled bin Ahmed Khalifa went to the extent of stating that it is not the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict but the threat from Iran which poses the gravest threat in the Middle East. Like some of the other delegates present at the Warsaw Conference, the Bahraini Foreign Minister accused Iran of providing logistical and financial support to militant groups in the region.

Similarly, another clip showed the Saudi Minister of State for Foreign Affairs (Adel al-Jubeir) saying that Iran was assisting and abetting terrorist organisations by providing ballistic missiles.

Iran was quick to dismiss the Middle East Conference in Warsaw, and questioned not just its legitimacy but also the outcome. Iranian President Hassan Rouhani stated that the conference produced an ‘empty result’.

US allies and their close ties with Iran

First, the US cannot overlook the business interests of its partners not just in Europe, but also in Asia such as Japan, Korea, and India. India for instance is not just dependent upon Iran for oil, but has invested in the Chabahar Port, which shall be its gateway to Afghanistan and Central Asia. New Delhi in fact has taken over operations of the Chabahar Port as of December 2018. On December 24, 2018, a meeting – Chabahar Trilateral Agreement meeting — was held and representatives from Afghanistan, Iran, and India jointly inaugurated the office of India Ports Global Chabahar Free Zone (IPGCFZ) at Chabahar.

The recent terror attacks in Iran as well as India have paved the way for New Delhi and Tehran to find common ground against terror emanating from Pakistan. On February 14, 2019, 40 of India’s paramilitary personnel were killed in Kashmir (India) in a suicide bombing (the dastardly attack is one of the worst in recent years). Dreaded terror group Jaish-E-Muhammad claimed responsibility. On February 13, 2019, 27 members of Iran’s elite Revolutionary Guards were killed in a suicide attack in the Sistan-Baluchistan province which shares a border with Pakistan. Iran has stated that this attack was carried out by a Pakistani national with the support of the Pakistani deep state.

Indian Foreign Minister Sushma Swaraj met with Iranian Deputy Foreign Minister Seyed Abbas Aragchchi en route to Bulgaria. In a tweet, the Iranian Deputy Foreign Minister stated that both sides had decided to strengthen cooperation to counter terrorism, and also said that ‘enough is enough’. This partnership is likely to grow, in fact many strategic commentators are pitching for an India-Afghanistan-Iran security trilateral to deal with terrorism.

Conclusion

So far, Trump’s Middle Eastern Policy has been focused on Iran, and his approach suits both Saudi Arabia and Israel but it is being firmly opposed by a number of US allies. It is important that the sane voices are heard, and no extreme steps are taken. As a result of the recent terror attack in Pulwama, geopolitical developments within South Asia are extremely important. Thus, the US and GCC countries will also need to keep a close watch on developments in South Asia, and how India-Pakistan ties pan out over the next few weeks. New Delhi may have its task cut out, but will have no option but to enhance links with Tehran. Trump needs to be more pragmatic towards Iran and should think of an approach which is acceptable to all, especially allies. New Delhi-Tehran security ties are likely to grow, and with China and Russia firmly backing Iran, the latter’s isolation is highly unlikely.

Nightcap

- Tensions between liberalism and democracy from a Tocquevillean perspective Ewa Atanassow (interview), JHIBlog

- High theory and low seriousness Gustav Jönsson, Quillette

- Another misuse of Eastern ideas Amy Olberding, Aeon

- The real reason Netflix is cancelling their Marvel shows Mark Hughes, Forbes

Afternoon Tea: Female Organ Player (1885)

From Gustav Klimt, still my favorite artist of all time…

Persecution & Toleration

I’m glad to announce that my new book, Persecution & Toleration (with my colleague Noel Johnson) is now available in the UK. I’m hoping to receive copies next week. The book is available at CUP, although Amazon still has a US release date of April (you can preorder it).

The blurb is below:

Religious freedom has become an emblematic value in the West. Embedded in constitutions and championed by politicians and thinkers across the political spectrum, it is to many an absolute value, something beyond question. Yet how it emerged, and why, remains widely misunderstood. Tracing the history of religious persecution from the Fall of Rome to the present-day, Noel D. Johnson and Mark Koyama provide a novel explanation of the birth of religious liberty. This book treats the subject in an integrative way by combining economic reasoning with historical evidence from medieval and early modern Europe. The authors elucidate the economic and political incentives that shaped the actions of political leaders during periods of state building and economic growth.

‘A profound new argument about the relationship between political power and religion in the making of the modern world. If you want to know where the liberty you currently enjoy, for now, came from, this is the book to read.’ James Robinson, Richard L. Pearson Professor of Global Conflict, University of Chicago

‘Johnson and Koyama investigate the fascinating intersection of the state and religion in late medieval and early modern Europe. Rather than enduring patterns of religious toleration or persecution, of liberty or tyranny, they tell a rich history of change and variation in rules, institutions, and societies. This is an important and persuasive book.’ John Joseph Wallis, Mancur Olson Professor of Economics, University of Maryland, College Park

‘Lucidly written, incisively argued, this book shows how religious toleration emerged not only from ideas, but also from institutions which motivated people – especially the powerful – to accept and act on those ideas. A brilliant account of early modern Europe’s transition from identity-based privileges to open markets and impartial governance.’ Sheilagh Ogilvie, University of Cambridge

‘This analysis of the historical process underlying the modern state formation is a fantastic scholarly accomplishment. The implications for the present, in terms of the risks associated to the loss of the core liberal values of modern western states, will not be lost to the careful reader.’ Alberto Bisin, New York University

Nightcap

- Is there an actual China-Japan thaw happening? Wijaya & Osaki, Diplomat

- The occupation of France after Napoleon Christine Haynes, Age of Revolutions

- Ilhan Omar and the power of clarity Michael Koplow, Ottomans & Zionists

- Blackmail! (Libertarian red meat!) Tyler Cowen, Marginal Revolution

The Gandalf Test

The two dominant American political parties have one defining trait in common, and it’s the trait that makes them both undeserving to hold the power they seek to wield. Both parties fail the Gandalf test.

I derive the Gandalf test from one of my favorite conversations in the Lord of the Rings. Gandalf pays a visit to Frodo Baggins after concluding that Bilbo’s old ring is in fact the One Ring–the single most dangerous and powerful object in Middle-earth. Once the full enormity of the ring dawns on Frodo, he tries to thrust it upon Gandalf. Gandalf flatly refuses. “With that power I should have power too great and terrible.” He recognized that he cannot embrace so much power even though he would want to do good with it. “Yet the way of the Ring to my heart is by pity, pity for weakness and the desire of strength to do good. Do not tempt me!”

The Gandalf test is simple: a righteous cause and a genuine desire to save the world do not qualify anyone for the exercise of extensive unilateral power. The Republican and Democratic Parties both have recently failed this test, and not for the first time. On one side, President Trump has turned to emergency powers to barge through constitutional barriers, so convinced he is that his cause is just. On the other side, the Green New Deal proposes to remake the United States economy. We tend to too often squabble over the merits of these policies instead of stepping back to apply the Gandalf test. Even if the policies themselves are good ones, even urgent ones, we must ask whether any person or cadre should wield the extraordinary power to put them into action. The “desire of strength to do good” is not enough.

A clear message of Gandalf’s and the Lord of the Rings generally is that progress toward the good and worthy comes through the everyday courage and goodness of ordinary people, not a few great souls on gilded thrones. Elsewhere, Gandalf points out: “Saruman believes it is only great power that can hold evil in check, but that is not what I have found. It is the small everyday deeds of ordinary folk that keeps the darkness at bay.” And in the Return of the King: “It is not our part to master all the tides of the world, but to do what is in us for the succour of those years wherein we are set, uprooting the evil in the fields that we know, so that those who live after may have clean earth to till. What weather they shall have is not ours to rule.” What a wonderfully apt response to the Green New Deal’s attempt to rule with an iron fist today in order to literally rule the weather that others might have tomorrow. That kind of hubris is poison to a republic.

We need to subject our leaders to the Gandalf test. We need to know if they are the type to vainly “master all the tides of the world,” or whether they will lead in humility by quietly empowering the everyday deeds of everyday people. If they can’t pass the test, I couldn’t care less whether they’re proposing a wall, a tax hike, or a clean energy revolution.