The Heidelberg Catechism is one of my all-time favorite Christian documents. Written in 1563, mostly by Zacharias Ursinus, the Heidelberg (as it is sometimes called) is composed by 129 questions and answers (the classical format of a catechism), supposed to be studied in 52 Sundays (that is, one year). I believe it is very telling that, being a catechism, the Heidelberg was written thinking mostly about younger people, even children. Ursinus himself was only about 29 years old when he wrote it. Maybe it is a sign of the times we live in that the Heidelberg sounds extremely deep for most readers today.

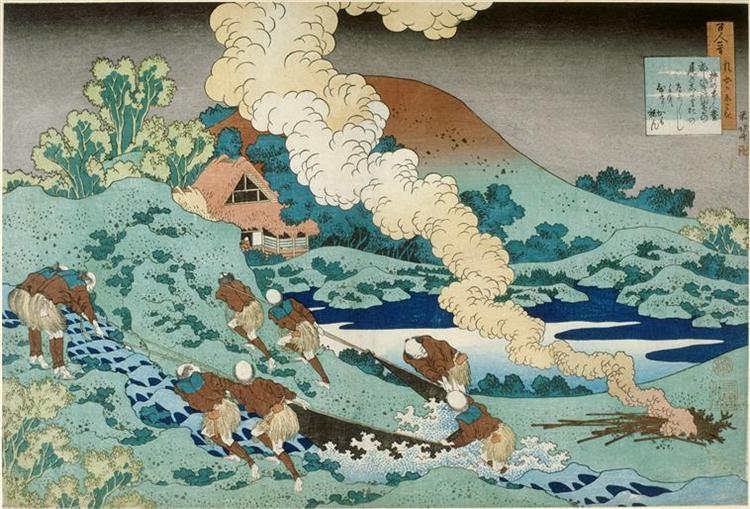

Throughout its questions and answers, the Heidelberg covers mostly three Christian documents: The Ten Commandments, the Lord’s Prayer (“Our Father who art in Heaven…”) and the Apostle’s Creed. The catechism is also divided into three main parts: Our sin and misery (questions 3-11), our redemption and freedom (questions 12-85), our gratitude and obedience (86-129). Probably an easier way to remember this is to say that the Heidelberg is divided into Guilt, Grace, and Gratitude. That is also, according to many interpreters, the basic division of the Apostle Paul’s Letter to the Romans, historically one of the most important books in the Bible.

I mention all these characteristics about the Heidelberg Catechism because I think they are worth commenting on. As I learned from a friend, that is the Gospel: Guilt, Grace, and Gratitude. As C.S. Lewis observed in Mere Christianity, Christians are divided on how exactly this works, but all agree that our relationship with God is strained. That is the guilt. However, in Jesus Christ, we can restart a peaceful relationship with God. That is the grace. This should be followed by a life of gratitude. That is the way the Gospel is good news. If you don’t emphasize these three points you are not really presenting the Biblical gospel. To talk about grace without talking about guilt is nonsense. To talk about guilt and not grace is not good news at all. To talk about guilt and grace but not of gratitude is antinomianism. To talk about gratitude (or obedience) without talking about guilt and especially grace is legalism. But also, notice how unbalanced the three main parts are: Ursinus dedicated way more space for grace and gratitude that he did for guilt.

That’s not accidental. Also, it is very interesting that he talks about the Ten Commandments when he is dealing with gratitude. It didn’t have to be this way. Ursinus could have included the Law when talking about guilt. He could use the law to show how miserable we are for not fulfilling it. But instead, he wanted to show that obeying God is a sign of gratitude. You are free already. Obeying will not make you any more saved. But it is certainly the behavior of a truly restored person.

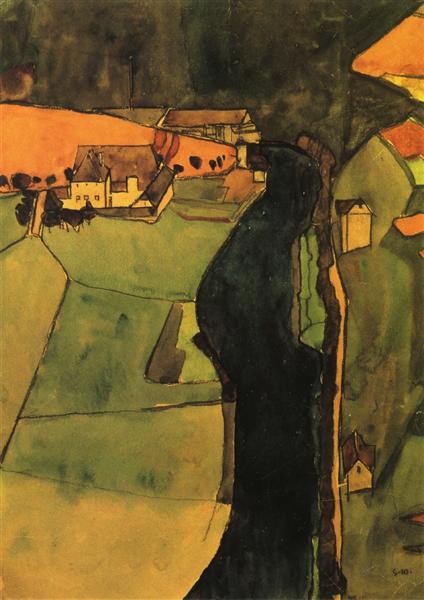

If you read so far, I should first thank you for your attention, but also say that I am completely unapologetic for speaking so openly on Christian themes. At some point in history, Christians decided to adapt to the modern culture. That was the birth of Christian Liberalism. Modern man, some of them assumed, could no longer believe in stories of gods and miracles. Modern science was able to explain things that societies in the past thought to be supernatural occurrences. The Bible was at worst pure nonsense or at beast a praiseful reflection of the piety of people in the past, but certainly not a supernatural revelation from God. But if you take away the supernatural elements of the Bible, what do you have left? Good morals, some thought. I believe they were wrong.

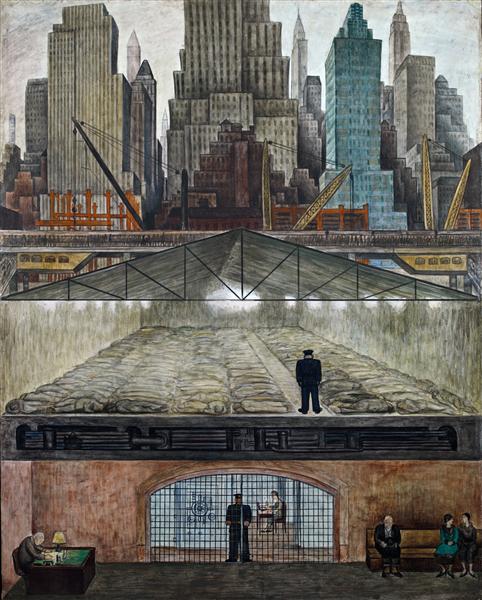

The social gospel is one consequence of Christian liberalism. The central miracle in the Bible is that Jesus, a mortal man, was dead for three days and resurrected. That is indeed a miracle. Make no mistake: people in the first century knew as well as we do that people don’t come back to life after three days. Maybe they knew it better than we do, for in the 21st century, for many of us, death is not a part of everyday life. For them, it certainly was. Christians have believed through almost two thousand years that Jesus’ death and resurrection have something to do with us being reconciled to God. But if Jesus didn’t resurrect, and no one really heard from God that he is angry, what do we have left? The answer, according to Christian liberals, is social justice. Reform society. I believe that for this, they own society at large an apology, and I will explain why.

I heard from too many people that the reason they don’t go to church is that Christians are hypocrites. “Do as I say, but not as I do”. Maybe they are right. The balance between guilt, grace, and gratitude if fundamental for Christianism to work. Salvation (reestablishing a rightful relationship with God) is by grace, not by works. Say that salvation is by works and you set the board in a way that you are sure to lose. As I already mentioned, I think it is just wonderful that the Heidelberg Catechism talks about the Law of God (The Ten Commandments) when it is discussing gratitude, not guilt, and I believe this is a great lesson for us today.

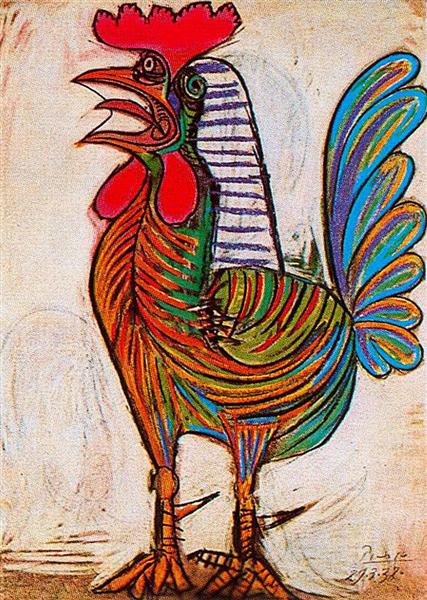

I say all this today because I believe that political correctness is (at least to a great degree) the bastard son (or daughter) of the social gospel. See the recent Gillette commercial that caused so much controversy, for example. Are they really saying anything wrong? Don’t men behave sometimes in ways that are less than commendable? I believe we do. Especially coming from a Latino culture as I do, I am more than willing to say that men all too often are disrespectful towards women and also towards other men. However, how the people at Gillette know this? If there is no God, or if he didn’t speak, how can you tell what is ethically commendable behavior and what is not?

I am no specialist, but as far as I know, more than enough atheist philosophers are willing to admit that in a sole materialist worldview there are no universal grounds for morality. As the poet said, “if there is no God, then all things are permissible”. It is always important in a conversation like this to explain that I am not saying that atheists cannot be ethical people. That is absolutely not what I am saying. Some of the best people I ever met were atheists. Some of the worst were Christians who were at church every single Sunday. With that explained, what I am saying is that there is no universal guide for human behavior if there is no God and everything just happened by chance. There are particular guides, but not a universal one, and to adhere to them is really a matter of choice.

The way that I see it, people at Gillette want men to feel bad and to change their behavior. They want men to feel guilty and to have gratitude. But where is the grace? I believe that is why this commercial irritated so many people. It makes people at Gillette look self-righteous or legalistic. Or both! But it definitely doesn’t help men to change their ways, supposing that there is something to change. I believe there is. There is a lot to change! But political correctness is not the way to do it.