Over the last week or so, I have been heavily involved in a twitterminar (yes, I am coining that portemanteau term to designate academic discussions on twitter – proof that some good can come out of social media) between myself, Judy Stephenson , Ben Schneider , Benjamin Guilbert, Mark Koyama, Pseudoerasmus, Anton Howes (whose main flaw is that he is from King’s College London while I am from the LSE – nothing rational here), Alan Fernihough and Lyman Stone. The topic? How suitable is the “high-wage economy” (HWE) explanation of the British industrial revolution (BIR).

Twitter debates are hard to follow and there is a need for summaries given the format of twitter. As a result, I am attempting such a summary here which is laced with my own comments regarding my skepticism and possible resolution venues.

An honest account of HWE

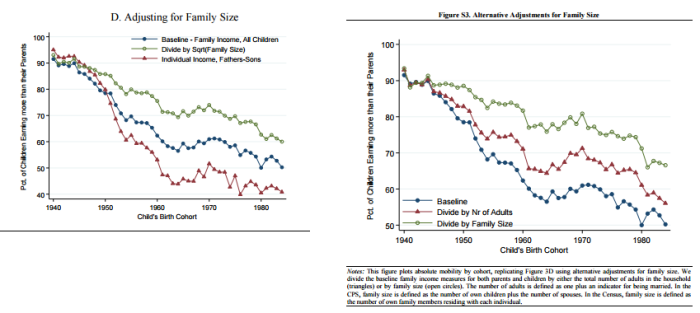

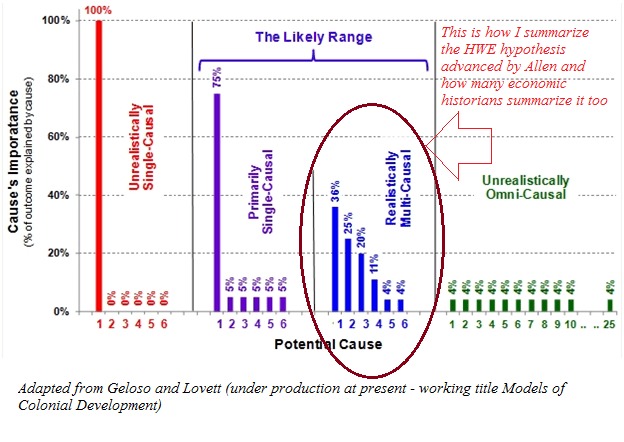

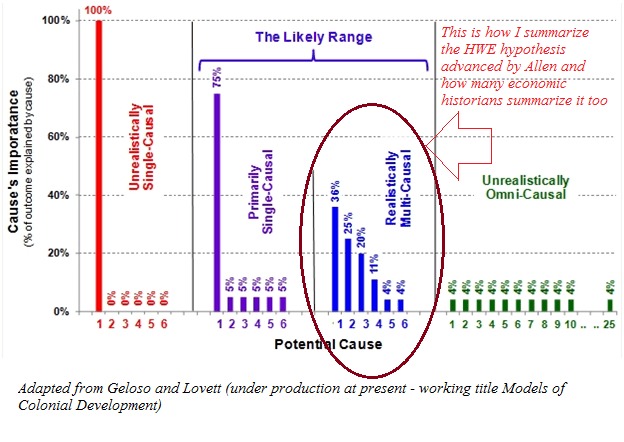

First of all, it is necessary to offer a proper enunciation of HWE’s role in explaining the industrial revolution as advanced by its main proponent, Robert Allen. This is a necessary step because there is a literature attempting to use high-wages as an efficiency wage argument. A good example is Morris Altman’s Economic Growth and the High-Wage Economy (see here too) Altman summarizes his “key message” as the idea that “improving the material well-being of workers, even prior to immediate increases in productivity can be expected to have positive effects on productivity through its impact on economic efficiency and technological change”. He also made the same argument with my native home province of Quebec relative to Ontario during the late 19th century. This is basically a multiple equilibria story. And its not exactly what Allen advances. Allen’s argument is that wages were high in England relative to energy. This factors price ratio stimulated the development of technologies and industries that spearheaded the BIR. This is basically a context-specific argument and not a “conventional” efficiency wage approach as that of Allen. There are similarities, but they are also considerable differences. Secondly, the HWE hypothesis is basically a meta-argument about the Industrial Revolution. It would be unfair to caricature it as an “overarching” explanation. Rather, the version of HWE advanced by Robert Allen (see his book here) is one where there are many factors at play but there is one – HWE – which had the strongest effects. Moreover, while it does not explain all, it was dependent on other factors that contributed independently. The most common view is that this is mixed with Joel Mokyr’s supply of inventions story (which is what Nick Crafts has done). In the graph below, the “realistically multi-causal” explanation is how I see HWE. In Allen’s explanation, it holds the place that cause #1 does. According to other economists, HWE holds spot #2 or spot #3 and Mokyr’s explanations holds spot #1.

In pure theoretical terms (as an axiomatic statement), the Allen model is defensible. It is a logically consistent construct. It has some questionnable assumptions, but it has no self-contradictions. Basically, any criticism of HWE must question the validity of the theory based on empirical evidence (see my argument with Graham Brownlow here) regarding the necessary conditions. This is the hallmark of Allen’s work: logical consistency. His work cannot be simply brushed aside – it is well argued and there is supportive evidence. The logical construction of his argument requires a deep discussion and any criticism that will convince must encompass many factors.

Why not France? Or How to Test HWE

As a doubter of Allen’s theory (I am willing to be convinced, hence my categorization as doubter), the best way to phrase my criticism is to ask the mirror of his question. Rather than asking “Why was the Industrial Revolution British”, I ask “Why Wasn’t it French”. This is what Allen does in his work when he asks explicitly “Why not France?” (p.203 of his book). The answer proposed is that English wages were high enough to justify the adoption of labor-saving technologies. In France, they were not. This led to differing rates of technological adoptions, an example of which is the spinning jenny.

This argument hinges on some key conditions :

- Wages were higher in England than in France

- Unit labor costs were higher in England than in France (productivity-adjusted wages) (a point made by Kelly, Mokyr and Ó Gráda)

- Market size factors are not sufficiently important to overshadow the effects of lower wages in France (R&D costs over market size mean a low fixed cost relative to potential market size)

- The work year is equal in France as in England

- The cost of energy in France relative to labor is higher than in England

- Output remained constant while hours fell – a contention at odds with the Industrious Revolution which the same as saying that marginal productivity moves inversely with working hours

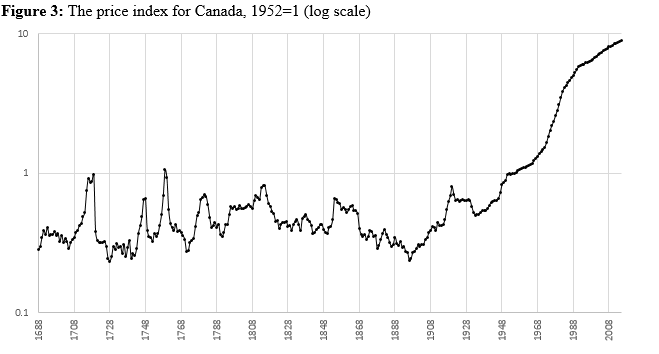

If most of these empirical statements hold, then the argument of Allen holds. I am pretty convinced by the evidence advanced by Allen (and E.A. Wrigley also) regarding the low relative of energy in England. Thus, I am pretty convinced that condition #5 holds. Moreover, given the increases in transport productivity within England (here and here), the limited barriers to internal trade (here), I would not be surprised that it was relatively easy to supply energy on the British market prior to 1800 (at least relative to France).

Condition #3 is harder to assess in terms of important. Market size, in a Smithian world, is not only about population (see scale effects literature). Market size is a function of transaction costs between individuals, a large share of which are determined by institutional arrangements. France has a much larger population than England so there could have been scale effects, but France also had more barriers to internal trade that could have limited market size. I will return to this below.

Condition #1,2,4 are basically empirical statements. They are also the main points of tactical assault on Allen’s theory. I think condition #1 is the easiest to tackle. I am currently writing a piece derived from my dissertation showing that – at least with regards to Strasbourg – wages in France presented in Allen (his 2001 article) are heavily underestimated (by somewhere between 12% and 40% using winter workers in agriculture and as much as 70% using the average for laborers in agriculture). The work of Judy Stephenson, Jane Humphries and Jacob Weisdorf has also thrown the level and trend of British wages into doubts. Bringing French wages upwards and British wages downwards could damage the Allen story. However, this would not be a sufficient theory. Industrialization was generally concentrated geographically. If labor markets in one country are not sufficiently integrated and the industrializing area (lets say the “textile” area of Lancashire or the French Manchester of Mulhouse or the Caën region in Normandy) has uniquely different wages, then Allen’s theory can hold since what matters is the local wage rate relative to energy. Pseudoerasmus has made this point but I can’t find any mention of that very plausible defense in Allen’s work.

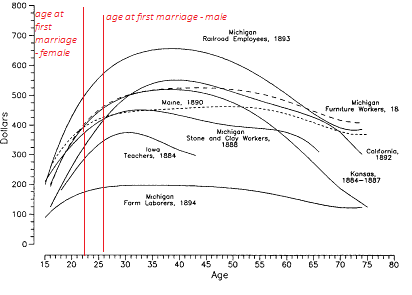

Condition #2 is the weakest point and given Robert Fogel’s work on net nutrition in France and England, I have no problem in assuming that French workers were less productive. However, the best evidence would be to extract piece rates in textile-producing regions of France and England. This would eliminate any issue with wages and measuring national productivity differences. Piece rates would perfectly capture productivity and thus the argument could be measured in a very straightforward manner.

Condition #4 is harder to assess and more research would be needed. However, it is the most crucial piece of evidence required to settle the issue once and for all. Pre-industrial labor markets are not exactly like those of modern days. Search costs were high which works in a manner described (with reservations) by Alan Manning in his work on monopsony but with much more frictions. In such a market, workers may be willing to trade in lower wage rates for longer work years. In fact, its like a job security argument. Would you prefer 313 days of work guaranteed at 1 shilling per day or a 10% chance of working 313 days for 1.5 shillings a day (I’ve skewed the hypothetical numbers to make my point)? Now, if there are differences in the structure of labor markets in France and England during the 18th and 19th centuries, there might be differences in the extent of that trade-off in both countries. Different average discount on wages would affect production methods. If French workers were prone to sacrifice more on wages for steady employment, it may render one production method more profitable than in England. Assessing the extent of the discount of annual to daily wages on both markets would identify this issue.

The remaining condition (condition #6) is, in my opinion, dead on arrival. Allen’s model, in the case of the spinning jenny, assumed that labor hours moved in an opposite direction as marginal productivity. This is in direct opposition to the well-established industrious revolution. This point has been made convincingly by Gragnolati, Moschella and Pugliese in the Journal of Economic History.

In terms of research strategy, getting piece rates, proper wage estimates and proper labor supplied estimates for England and France would resolve most of the issue. Condition #3 could then be assessed as a plausibility residual. Once we know about working hours, actual productivity and real wages differences, we can test how big the difference in market size has to be to deter adoption in France. If the difference seems implausible (given the empirical limitations of measuring effective market size in the 18th century in both markets), then we can assess the presence of this condition.

My counter-argument : social networks and diffusion

For the sake of argument, let’s imagine that all of the evidence favors the skeptics, then what? It is all well and good to tear down the edifice but we are left with a gaping hole and everything starts again. It would be great to propose a new edifice as the old one is being questioned. This is where I am very much enclined towards the rarely discussed work of Leonard Dudley (Mothers of Innovation). Simply put, Dudley’s argument is that social networks allowed the diffusion of technologies within England that fostered economic growth. He has an analogy from physics which gets the point across nicely. Matter has three states : solid, gas, liquid. Solids are stable but resist to change. Gas, matter are much more random and change frequently by interacting with other gas, but any relation is ephemeral. Liquids permit change through interaction, but they are stable enough to allow interactions to persist for some time. Technological innovation is like a liquid. It can “mix” things together in a somewhat stable form.

This is where one of my argument takes life. In a small article for Economic Affairs, I argued (expanding on Dudley) that social networks allowed this mixing (I am also expanding that argument in a working paper with Adam Martin of Texas Tech University). However, I added a twist to that argument which I imported from the work of Israel Kirzner (one of the most cited books in economics, but not by cliometricians – more than 7000 citations on google scholar). Economic growth, in Kirzner’s mind, is the result of entrepreneurs discovering errors and arbitrage possibilities. In a way, growth is a process of discovering correcting errors. An analogy to make this point is that entrepreneurs look for profits where the light is while also trying to move the light to see where it is dark. What Kirzner dubs as “alertness” is in fact nothing else than repeated and frequent interactions. The more your interact with others, the easier it becomes for ideas to have sex. Thus, what matters is how easy it is for social networks to appear and generate cheap information and interactions for members without the problem of free riders. This is where the work of Anton Howes becomes very valuable. Howes, in his PhD thesis supervised by Adam Martin who is my co-author on the aforementioned project (summary here), showed that most innovators went in frequent with one another and they inspired themselves from each other. This is alertness ignited!

If properly harnessed, the combination of the works of Howes and Dudley (and also James Dowey who was a PhD student at the LSE with me and whose work is *Trump voice* Amazing) can stand as a substitute to Allen’s HWE if invalidated.

Conclusion

If I came across as bashing on Allen in this post, then you have misread me. I admire Allen for the clarity of his reasoning and his expositions (given that I am working on a funded project to recalculate tax-based measures in the US used by Piketty to account for tax avoidance, I can appreciate the clarity in which Allen expresses himself). I also admire him for wanting to “Go big or go home” (which you can see in all his other work, especially on enclosures). My point is that I am willing to be convinced of HWE, but I find that the evidence leans towards rejecting it. But that is very limited and flawed evidence and asserting this clearly is hard (as some of the flaws can go his way). Nitpicking Allen’s HWE is a necessary step for clearly determining the cause of BIR. It is not sufficient as a logically consistent substitute must be presented to the research community. In any case, there is my long summary of the twitteminar (officially trademarked now!)

P.S. Inspired by Peter Bent’s INET research webinar on institutional responses to financial crises, I am trying to organize a similar (low-cost) venue for presenting research papers on HWE assessment. More news on this later.