Switzerland has recently overwhelming voted against a proposal that would establish a universal income guarantee (sometimes called a “basic income guarantee” or the similar Friedman-influenced “negative income tax”[1]). Though I myself am a supporter of BIG as a nth best policy alternative for pragmatic reasons,[2] I’m unsure if I myself would have voted for this specific policy proposal due to the lack of specifics. A basic income is only as good as the welfare regime surrounding it (which preferably would be very limited) and the tax system that funds it.[3] However, the surprising degree of unpopularity of the proposal—with 76.9% voting against—was quite surprising.

The Swiss vote has renewed debate in the more wonkish press and blogosphere, as well as in think tanks, about the merits and defects of a Basic Income Guarantee here in the States. For example, Robert Goldstein of the Center on Budget Policy and Priorities[4] has a piece arguing that a BIG would increase poverty if implemented as a replacement for the current welfare state. His argument covers three points:

- A BIG would be extremely costly to the point of being impossible to fund.

- A BIG would increase the poverty rate by replacing current welfare programs like Medicaid and SNAP.

- A universal welfare program like a BIG—as opposed to means-tested programs—is politically impossible right now due to its unpopularity.

For this post, I’ll analyze Goldstein’s arguments in detail. Overall, I do not find his arguments against a BIG convincing at all.

The Political Impossibility of a BIG

Goldstein writes:

Some UBI supporters stress that it would be universal. One often hears that means-tested programs eventually get crushed politically while universal programs do well. But the evidence doesn’t support that belief. While cash aid for poor people who aren’t working has fared poorly politically, means-tested programs as a whole have done well. Recent decades have witnessed large expansions of SNAP, Medicaid, the EITC, and other programs.

If anything, means-tested programs have fared somewhat better than universal programs in the last several decades. Since 1980, policymakers in Washington and in a number of states have cut unemployment insurance, contributing to a substantial decline in the share of jobless Americans — now below 30 percent — who receive unemployment benefits. In addition, the 1983 Social Security deal raised the program’s retirement age from 65 to 67, ultimately generating a 14 percent benefit cut for all beneficiaries, regardless of the age at which someone begins drawing benefits. Meanwhile, means-tested benefits overall have substantially expanded despite periodic attacks from the right. The most recent expansion occurred in December when policymakers made permanent significant expansions of the EITC and the low-income part of the Child Tax Credit that were due to expire after 2017.

In recent decades, conservatives generally have been more willing to accept expansions of means-tested programs than universal ones, largely due to the substantially lower costs they carry (which means they exert less pressure on total government spending and taxes).

I agree that Goldstein is right on this point: universal welfare programs are extremely unpopular right now, like the Swiss vote shows. I imagine that if a proposal were on the ballot in the States the outcome would be similar.[5] However, this is no argument against a Basic Income. Advocating politically unpopular though morally and economically superior policies is precisely the role academics and think tank wonks like Goldstein should take.

If something is outside the Overton Window of Political Possibilities, it won’t necessarily be so in the future if policymakers can make the case for it effectively to voters and the “second-hand dealer of ideas” in think tanks and academia get their ideas “in the air,” so to speak.[6] It wasn’t that long ago that immigration reform or healthcare reform seemed politically impossible due to its unpopularity, yet the ladder has popular support and the former was actually accomplished.[7]

If anything, the unpopularity of a BIG is precisely why people like Goldstein should advocate for the policy.

The Fiscal Costs of Funding a Basic Income Guarantee

Goldstein points out, rightly, that a Basic Income Guarantee would be extremely expensive:

There are over 300 million Americans today. Suppose UBI provided everyone with $10,000 a year. That would cost more than $3 trillion a year — and $30 trillion to $40 trillion over ten years.

This single-year figure equals more than three-fourths of the entire yearly federal budget — and double the entire budget outside Social Security, Medicare, defense, and interest payments. It’s also equal to close to 100 percent of all tax revenue the federal government collects.

Or, consider UBI that gives everyone $5,000 a year. That would provide income equal to about two-fifths of the poverty line for an individual (which is a projected $12,700 in 2016) and less than the poverty line for a family of four ($24,800). But it would cost as much as the entire federal budget outside Social Security, Medicare, defense, and interest payments.

Where would the money to finance such a large expenditure come from? That it would come mainly or entirely from new taxes isn’t plausible. We’ll already need substantial new revenues in the coming decades to help keep Social Security and Medicare solvent and avoid large benefit cuts in them. We’ll need further tax increases to help repair a crumbling infrastructure that will otherwise impede economic growth. And if we want to create more opportunity and reduce racial and other barriers and inequities, we’ll also need to raise new revenues to invest more in areas like pre-school education, child care, college affordability, and revitalizing segregated inner-city communities.

Of course, Goldstein is right that a BIG would be fairly expensive and we are already having serious issues funding our existing welfare state. However, he grossly oversells the difficulty in funding it. In particular, it is not necessary to raise taxes to pay for it or for current welfare expenditures.

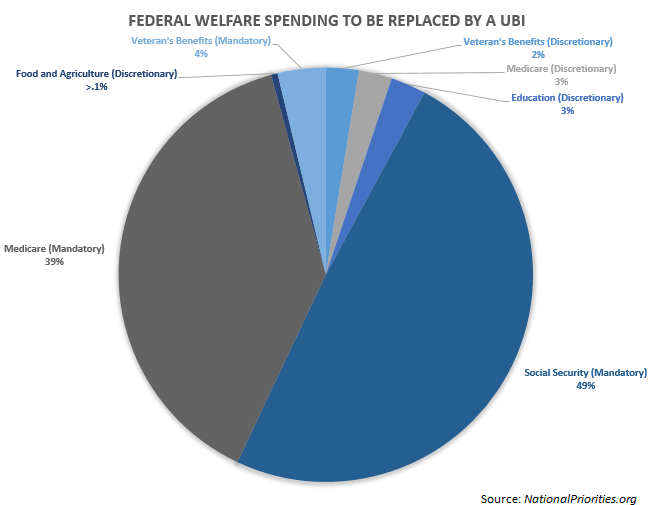

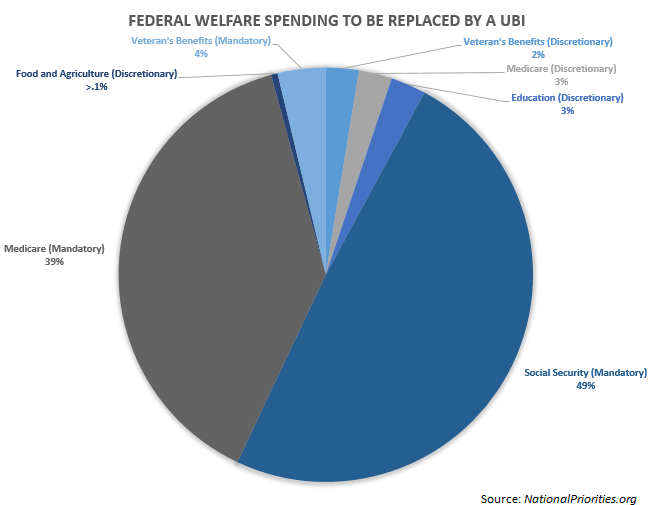

Goldstein likely gets the $10,000 figure from Charles Murray’s proposal for a BIG. Personally, I’m no fan of Murray’s proposal as it goes too far and he proposes financing it by increasing payroll taxes, which are economically inefficient. However, let’s assume that the relevant proposal is around $7,000 dollars.[8] Multiplying that by the US population of 320 million makes for a total cost $2.24 trillion per year.[9] This could be paid for by using the BIG to replace the following current welfare programs and cutting discretionary spending:[10]

- $65.32 billion annually in discretionary spending on Veteran’s benefits

- $66.03 billion in discretionary spending on Medicare and other healthcare benefits

- $69.98 billion in discretionary spending for education.[11]

- $13.13 billion in discretionary spending for food and agriculture (eg., SNAP).[12]

- $1.25 trillion in mandatory spending for Social Security.[13]

- $985.74 billion in mandatory spending for Medicare and Healthcare.

- $95.3 billion in mandatory spending for veteran’s benefits.[14]

That’s a total of $2.542 trillion in savings annually, more than enough to fund the proposed BIG with another $300.3 billion to spare that could be used for tax credits for low-income households to use on healthcare,[15] education,[16] retirement,[17] and/or basic necessities like food.[18] Funding the program would be a huge challenge, but it is possible to do it without tax increases.

Additionally, Goldstein ignores the fact that similar proposals, such as Friedman’s negative income tax, would have a much lower cost while having a similar effect. The Niskanen Center’s Samuel Hammond has estimated that a NIT could cost only $182 billion annually.[19] From Hammond’s analysis:

Just how much of a cost difference is there between a UBI and NIT? To get a rough idea, I used the Census population survey’s Annual Social and Economic Supplement, which has the distribution of individuals over the age of 15 by income level in $2,500 intervals (I subtracted retirees). I then calculated the transfer each quantile would receive based on a hypothetical NIT which starts at $5,000 for individuals with zero income and is phased out at a rate of 30%. Multiplying the average transfer by the number of actual individuals in each grouping and summing, I arrived at total cost of $182 billion—roughly the combined budget for SSI, SNAP and EITC.

The Effect of Replacing Welfare with a BIG on Poverty

Goldstein would object to my line of reasoning by saying cutting all that spending would harm the poor and increase the poverty rate. He says as much in his piece:

UBI’s daunting financing challenges raise fundamental questions about its political feasibility, both now and in coming decades. Proponents often speak of an emerging left-right coalition to support it. But consider what UBI’s supporters on the right advocate. They generally propose UBI as a replacement for the current “welfare state.” That is, they would finance UBI by eliminating all or most programs for people with low or modest incomes.

….Yet that’s the platform on which the (limited) support for UBI on the right largely rests. It entails abolishing programs from SNAP (food stamps), which largely eliminated the severe child malnutrition found in parts of the Southern “black belt” and Appalachia in the late 1960s, the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), Section 8 rental vouchers, Medicaid, Head Start, child care assistance, and many others. These programs lift tens of millions of people, including millions of children, out of poverty each year and make tens of millions more less poor.

Some UBI proponents may argue that by ending current programs, we’d reap large administrative savings that we could convert into UBI payments. But that’s mistaken. For the major means-tested programs — SNAP, Medicaid, the EITC, housing vouchers, Supplemental Security Income (SSI), and school meals — administrative costs consume only 1 to 9 percent of program resources, as a CBPP analysis explains. Their funding goes overwhelmingly to boost the incomes and purchasing power of low-income families.[20]

Moreover, as the Roosevelt Institute’s Mike Konczal has noted, eliminating Medicaid, SNAP, the EITC, housing vouchers, and the like would still leave you far short of what’s needed to finance a meaningful UBI. Would we also end Pell Grants that help low-income students afford college? Would we terminate support for children in foster care, for mental health, and for job training services?

This is by far and away the weakest part of Goldstein’s argument.

First of all, as my analysis above showed, Konczal’s and Goldstein’s idea that eliminating the current welfare state “would still leave you far short of what’s needed to finance a meaningful UBI” is just false. Even a relatively robust UBI of $7,000 a year is doable by significantly cutting current welfare programs.

But more importantly, Goldstein’s assertion that replacing the welfare state with a UBI would increase poverty is fully unwarranted. He seems to take a ridiculously unsophisticated idea that “more means-tested programs immediately reduce welfare.” His assertion that the programs in question “lift tens of millions of people, including millions of children, out of poverty each year and make tens of millions more less poor” is, at best, completely erroneous. For three reasons: first, individuals know better what they need to lift themselves out of the than the government, and these programs assume the opposite. Second, the structure of status quo means-tested programs often creates a “poverty trap” which incentivizes households to remain below the poverty line. Finally, thanks to these first two theoretical reasons, the empirical evidence on the success of the status-quo programs in terms of reducing the poverty rate is, at best, mixed.

The way our current welfare state is structured is it allocates how much money can go to what basic necessities for welfare recipients. So if a household gets $10,000 in welfare a year, the government mandates that, say, $3,000 goes to food, $3,000 goes to healthcare, $3,000 goes to education, and $1,000 goes to retirement.[21] This essentially assumes that all individuals and households have the same needs; but this is simply not the case, elderly people may need more money for healthcare and less for education, younger people may need the exact opposite, and poorer families with children may need more for food and education than other needs. It’s almost as if our current welfare system assumes interpersonal utility function comparisons are possible, or utility functions of poorer people are fairly homogenous but they’re not. It also ignores the opportunity cost of the funding for helping individuals and households out of funding; a dollar spent on healthcare may be more effectively spent on food for a particular individual or household.

In sum, there’s a knowledge problem involved in our current welfare policy to combat poverty: the government cannot know the needs of impoverished individuals, and such knowledge is largely dispersed, tacit, and possessed by the individuals themselves. The chief merit of a UBI is, rather than telling poor people what they can spend their welfare on, it just gives them the money and lets them spend it as they need.

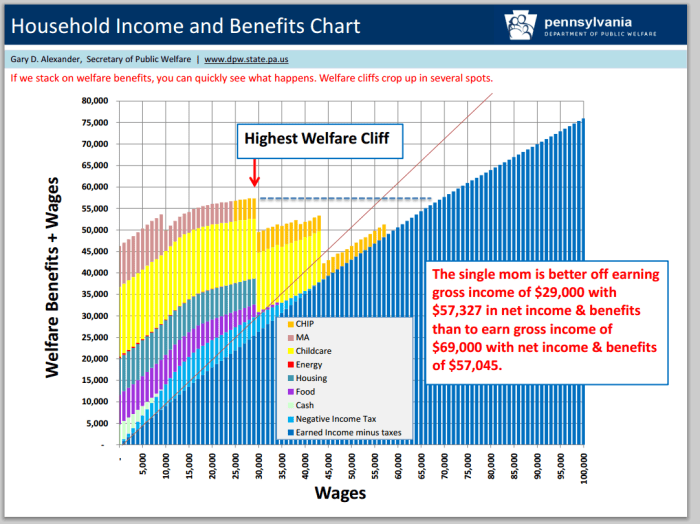

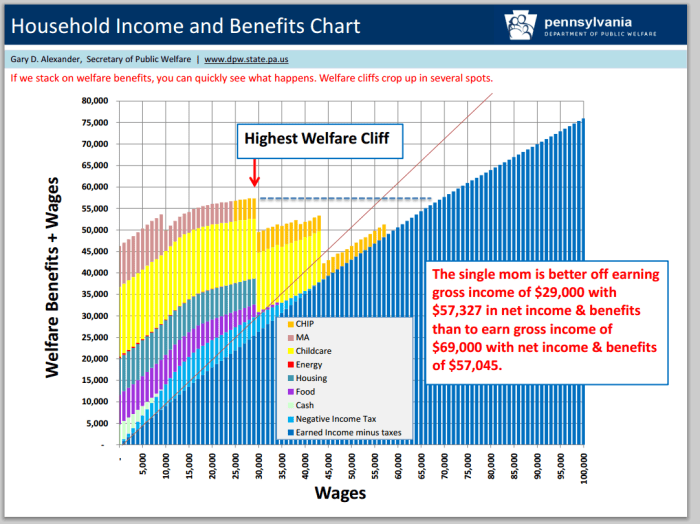

Second, universal programs are superior to means tested programs precisely because the amount of transfer payments received does not decrease as income increases. Our current welfare programs too often make the marginal cost of earning an additional dollar, above a certain threshold, higher than the benefits because transfer payments are cut-off at that threshold. This actually perversely incentivizes households to remain in poverty.[22] For example, the Illinois Policy Institute while analyzing welfare in Illinois found the following:

A single mom has the most resources available to her family when she works full time at a wage of $8.25 to $12 an hour. Disturbingly, taking a pay increase to $18 an hour can leave her with about one-third fewer total resources (net income and government benefits). In order to make work “pay” again, she would need an hourly wage of $38 to mitigate the impact of lost benefits and higher taxes.

Or consider this chart (shown above) from the Pennsylvania Department of Public Welfare showing the same effect in Pennsylvania

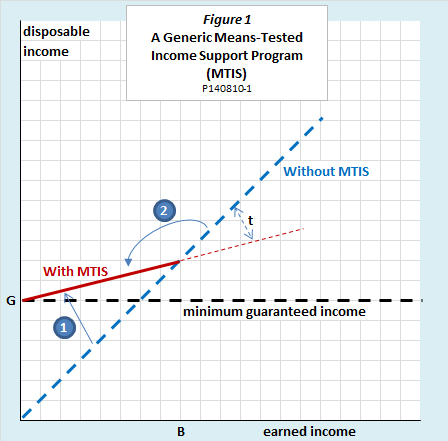

UBI does not suffer from this effect. If your income goes up, you do not lose benefits and so there are no perverse incentives at work here. Ed Dolan has analyzed how the current welfare state with its means-tested benefits is worse in terms of incentivizing work and alleviating poverty extensively. Here’s a slice of his analysis:

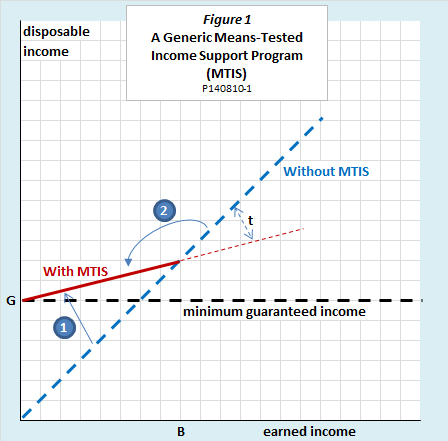

The horizontal axis in Figure 1 represents earned income while the vertical axis shows disposable income, that is, earned income plus benefits. To keep things simple, we will assume no income or payroll taxes on earned income—an assumption that I will briefly return to near the end of the post. The dashed 45o line shows that earned and disposable income are the same when there are no taxes or income support. The solid red line shows the relationship between disposable and earned income with the MTIS policy.

This generic MTIS policy has three features:

A minimum guaranteed income, G, that households receive if they have no earned income at all.

A benefit reduction rate (or effective marginal tax rate), t, indicted by the angle between the 45o line and the red MTIS schedule. The fact that t is greater than zero is what we mean when we say that the program is means tested. As the figure is drawn, t = .75, that is, benefits are reduced by 75 cents for each dollar earned.

A break-even income level, beyond which benefits stop. Past that point, earned income equals disposable income.

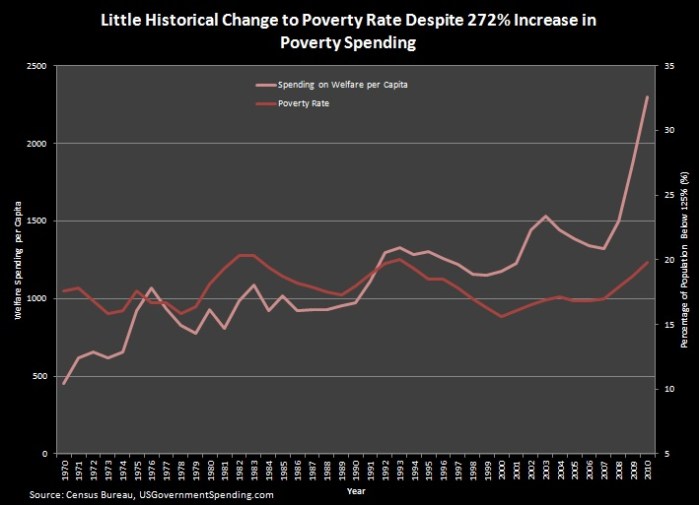

When these two factors are taken into account (that individuals know better than the government what they need to get out of poverty and there are significant poverty traps in our welfare state), it is no surprised that the empirical evidence on the effectiveness of these anti-poverty programs is far less rosy than Goldstein seem to think.

After reviewing the empirical literature on the relationship between income and welfare improvements for impoverished households, Columbia University’s Jane Waldfogel concluded “we cannot be certain whether and how much child outcomes could be improved by transferring income to low income families.” The Cato Institute’s Michael Tanner wrote in 2006:

Yet, last year, the federal government spent more than $477 billion on some 50 different programs to fight poverty. That amounts to $12,892 for every poor man, woman, and child in this country. And it does not even begin to count welfare spending by state and local governments. For all the talk about Republican budget cuts, spending on these social programs has increased an inflation-adjusted 22 percent since President Bush took office.

Despite this government largesse, 37 million Americans continue to live in poverty. In fact, despite nearly $9 trillion in total welfare spending since Lyndon Johnson declared War on Poverty in 1964, the poverty rate is perilously close to where it was when we began, more than 40 years ago.

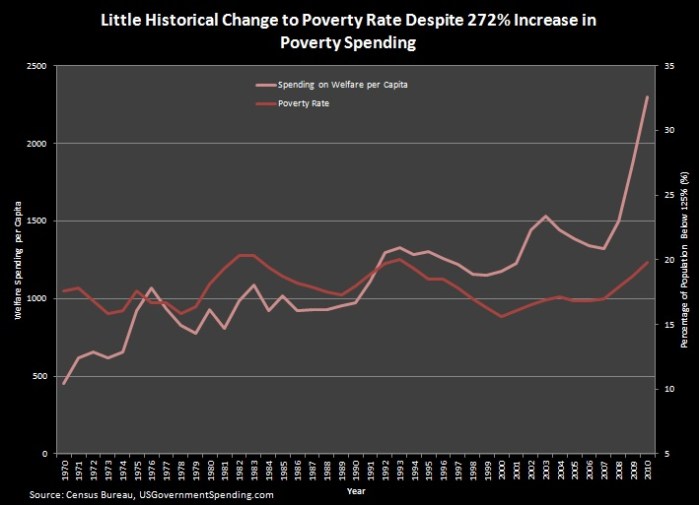

Tanner’s point remains true today. The chart below shows that, despite a massive increase in anti-poverty spending since the war on poverty was declared under Johnson’s “Great Society,” Poverty rates have remained woefully stagnant. In fact, the reduction in poverty that was occurring prior to Johnson’s interventions stopped soon thereafter.

Also, the point is that UBI is a replacement for current welfare benefits. Most households probably would not see a decrease in amount of benefits under a UBI, depending on the specifics of the proposal, and some might even see an increase, contrary to Goldstein’s analysis. Further, they’d be able to actually spend this on what they know they need rather than what government bureaucrats thin they need.

UBI lacks the flaws of the current welfare state, and would likely decrease poverty far more effectively than Goldstein thinks, especially when compared to his favored status-quo.

[1] Though there are some technical differences between Milton Friedman’s proposal for a “negative income tax” and most Basic Income Guarantee proposals, they essentially have the same effect on income. See the Adam Smith Institute’s Sam Bowmen on this point.

[2] See Matt Zwolinski for the “Pragmatic Libertarian Case for a Basic Income,” it should be noted that “pragmatic reasons” here does not refer to my pragmatist philosophical views. Zwolinski has also made a moral case for the basic income on Hayekian grounds that a BIG could reduce coercion in labor negations. I am unsure to what extent I am convinced by this line of reasoning, but it is a valid argument nonetheless.

[3] The Niskanen Center’s Samuel Hammond has made the case that universal transfer programs like a Basic Income cannot be analyzed outside of the tax system that pays for it.”

[4] Or, as my think tank buddies jokingly call it, the “Center for Bigger Budgets.”

[5] Having said that, polls have shown that it is popular across the pond in the Eurozone. The Swiss proposal would call into question this point but it could be argued that the vagueness of the Swiss proposal is why it was turned down not necessarily the spirit of it.

[6] My colleague Ty Hicks of Students for Liberty has made this point well. See also Hayek’s “Intellectuals and Socialism.”

[7] Granted, the Affordable Care Act was not really what most on the left or the right wanted in the first place and has been a disaster.

[8] This number is selected because, according to the CBO, $9,000 is the average amount in means-tested welfare benefits per household for 2006. But that’s for households and a BIG discussed here is for individuals, so it is understandable to make a BIG slightly less than the current average. Goldstein would object that this is far below the poverty line, but BIG is not meant to be a replacement for total income on the labor market at all, so it is unclear why this is an objection in the first place.

[9] This is admittedly a crude and naïve calculation but it is virtually identical to the method Goldstein himself uses to estimate the cost.

[10] All figures for this section are for the 2015 budget and are taken from here.

[11] Goldstein is sure not to be happy with cutting education, and I myself would like to replace this spending with few-strings-attached funding for local education or private school tax vouchers. I’ll address this point more later in this piece.

[12] Much of this is food stamps, which would be rendered obsolete by a BIG anyways. Goldstein would object, more on that in the next section.

[13] Not all of this could be cut, and there would be legal and detailed nuances on how to treat financial obligations for Social Security, veteran’s benefits, and Medicare. The specific legal complexities of mandatory welfare spending are not my areas of expertise, admittedly, and is outside the scope of this paper. I’m just illustrating that it is possible to cut at least some of this spending, perhaps even the majority of it, to fund it.

[14] Many people would object to cutting veterans benefits. First of all, BIG could act in place of these benefits

[15] I have in mind expanding tax-exempt Health Savings Accounts here. I also think funding this by eliminating the employer-based deduction would be a step in the right direction and reduce cost fragmentation in the healthcare market, as Milton Freidman argued.

[16] I have in mind a private school taxpayer voucher system like what is in Sweden.

[17] I have in mind something similar to this proposal to reform social security from the Cato Institute.

[18] I have in mind something like the pre-bates proposed in the Fair Tax.

[19] For this reason, I prefer an NIT to a BIG, but I prefer both to our current welfare state.

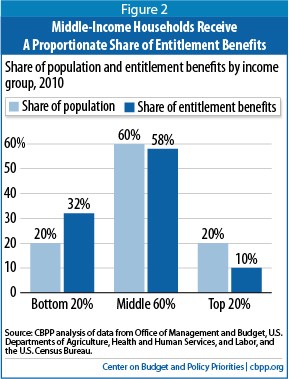

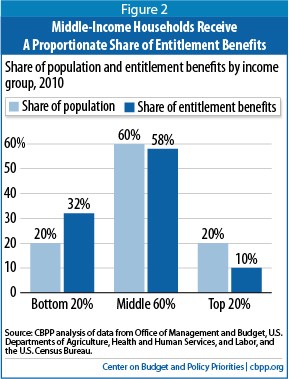

[20] This point is Ironic considering the fact that CBPP’s own research shows that government benefits in America overwhelmingly goes to households above the poverty line, in the middle and upper classes. See this chart (source):

[21] The real-world numbers are probably different and vary a little bit from household to household, but this is just a hypothetical to illustrate a more general point.

[22] It should be noted, however, that the EITC, and some other programs, is largely free of this defect. This is because the EITC itself is modeled after Friedman’s NIT.

Note: The first chart has been edited since this was initially posted for readability.