In the course of the twitterminar on the High-Wage Economy argument (HWE) which generated responses from John Styles on his blog (who has convinced me that the key solution to HWE rests in Normandy, not the Alsace) and many other on Twitter. In the course of that discussion, I skirted a point I have been meaning to make for a long time. However, I decided to avoid it because it is tangentially related to the HWE story. Its about how we measure living standards over space in the past.

Basically, the HWE story is a productivity story and all that matters in such a story is wage rates relative to other input prices. Because we’re talking about relatives, the importance of proper deflators is not that crucial. However, when you move beyond HWE and try to ask the question regarding absolute differences over space in living standards, the wage rates are not sufficient and proper deflators are needed.

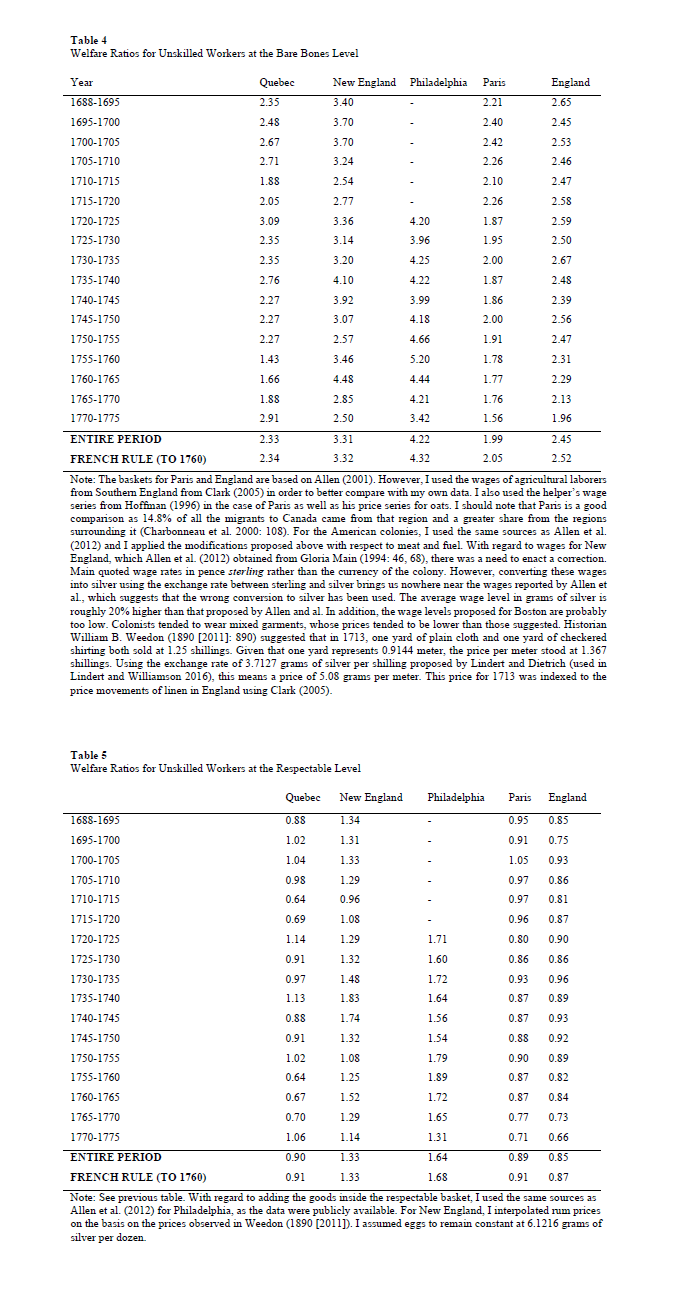

They are many key issues to estimating living standards across space. The largest is that given that very few goods crossed borders in the past, converting American incomes into British sterling units using reported exchange rates would be rife with errors and calculating purchasing power parities would be complicated. The solution, very simple and elegant by its simplicity, is to rely on the logic of the poverty measures. Regardless of where you are, there is a poverty threshold. Then, all that is needed is to express incomes as the ratio of income to the poverty line. If the figure is three, then the average income buys three times the poverty line. Expressed as such, comparisons are easy to do. This is what Robert Allen did and it was basically a deeper and more complete approach than Fernand Braudel’s “Grain-Wages” (wage rates divided by grain prices).

Where should the line be?

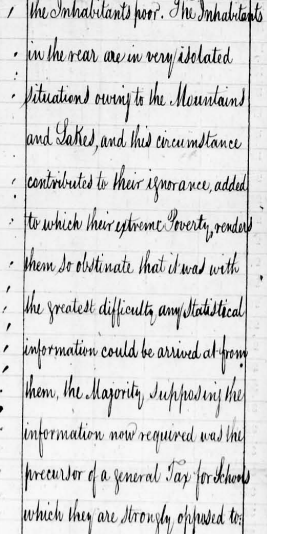

While this represents a substantial improvement for economic historians like me who are deeply interested in “getting the data right”, there are flaws. In the course of my dissertation on living standards in Canada (see also my working papers here and here), I saw one such flaw in the form of how long the length of the work year was. In fact, a lot of my comments in this post were learned on the basis of Canada as an extreme outlier in terms of sensitivity. In Canada, winter is basically a huge preindustrial limitation on the ability to work year-round (thus, the expression mon pays ce n’est pas un pays, c’est l’hiver). But this flaw is only the tip of the iceberg. First of all, the winter means that the daily energy intake must substantially greater than 2,500 calories in order to maintain body mass. The mechanism through which the temperature increases the energy requirements of the human metabolism is in part the greater weight carried by the heavier clothing in addition to the energy needed by the body to maintain body temperature. At higher altitudes, these are compounded by the difference in air pressure.In their attempt to construct estimates of the living standards of Natives in the Canadian north during the fur trade era, Ann Carlos and Frank Lewis assert that it is necessary to adjust the basket of comparison to include more calories for the natives given the climate – they assert that 3500 calories were needed rather 2500 calories for English workers.In Russia, Boris Mironov estimated that the average calories ingested stood at 2952 per day between 1865 and 1915 while the adult male had to consume 3204 calories per day. In Canada in the 18th century, it was estimated that patients at the Augustines hospital in Quebec City required somewhere 2628 calories and 3504 calories per day while soldiers consumed on average 2958 calories per day and the average population consumed 2845 calories per day (see my papers linked up above). The range of calorie requirements for soldiers (which I took from a reference inside my little sister’s military stuff) is quite large: from 3,100 in the desert at 33 degrees Celsius to 4,900 in artic conditions (minus 34 degrees Celsius) – a 58% difference. So basically, when we create welfare ratios for someone in, say, Mexico, the calories needed in the basket should be lower than in the Canadian basket.

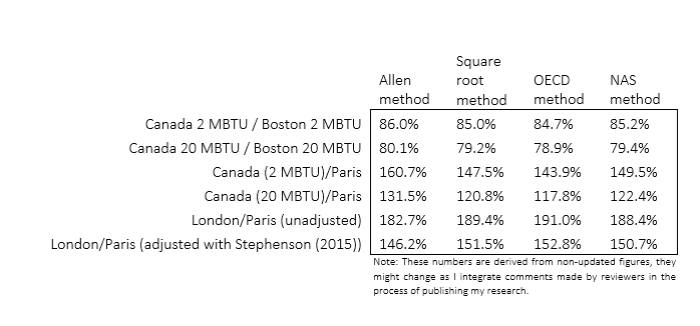

Another issue, of greater importance, is the role of fuel. In the welfare ratios commonly used, fuel is alloted at 2MBTU for the basic level of sustenance which. This is woefully insufficient even in moderately warm countries, let alone Canada. My estimates of fuel consumption in Canada is that the worst case hovers around 20MBTU (ten times above the assumption) if the most inefficient form of combustion (important losses) and the worst kind of wood possible (red pine). Similar levels are observed for the American colonies.

Combined together, these corrections suggest that the Canadian poverty threshold should be higher than the one observed in France, England, South Carolina or Argentina. These adjustments can more or less be easily made by using military manuals. The army measures the basic calories requirements for all types of military theaters.

How to factor in family size and use equivalence scales.

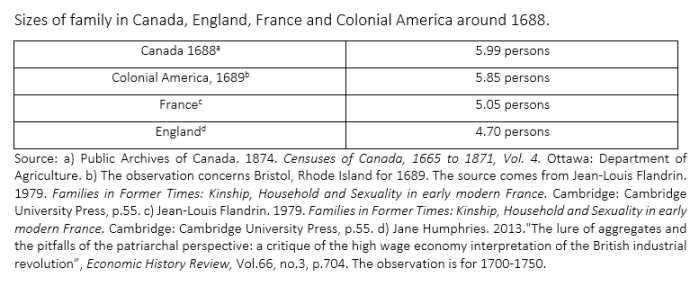

Equivalence scales refer to the role of family size. Given the same income, families of different size will have different levels of welfare. Thanks to economies of scale in housing, cooking, lighting and heating, larger households can get more utility out of one dollar of income. That adjustments are required to render different households comparable is well accepted amongst economists. However, given the sensitivity of any analysis to the assumptions underlying any adjustments, there is an important debate to be had.

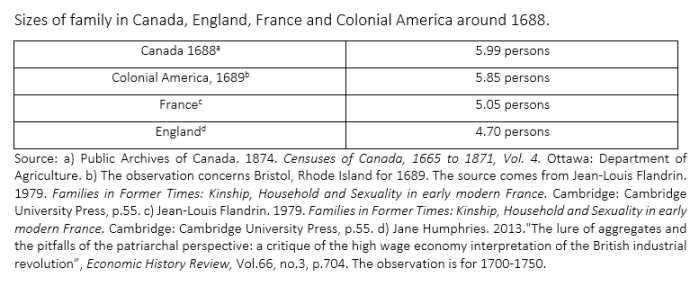

The convention among economic historians has been to assume that households have three adult equivalents. This assumption has gone largely undiscussed. The problem is “which scale to use”. The conversion into adult equivalents is subject to debates. Broadly speaking, three approaches exist. The first uses the square root of the number of individuals. The second attributes the full weight of the first adult, half the weight of the second adult and 30% for each child. This approach is commonly used by the OECD, Statistics Canada and numerous government agencies in Canada The third approach is the one used by the National Academy of Sciences in the United States which proposed to use an exponent ranging between 0.65 and 0.75 to household size but only after having multiplied the number of children by 0.7. As a result, a family of four (two parents, two infants) can have either 2 adult equivalents (square root), 2.1 adult equivalents (OECD and Statistics Canada approach) or 2.36 adult equivalent (NAS approach). The differences relative to the square roots approach are 5% and 18%. If we move to a family of 6 persons, the differences increase to 10.22% and 34.72%. If we are comparing regions with identical family structures, this would not be a problem. If not, then it is an issue. The selection of one method over another would have important effect on the cost of the living basket, with the NAS approach showing the costliest basket. Using a method relatively close to that of the OECD (although not exactly that measure), Eric Schneider found that the relatively small size of families in England led Allen to underestimate living standards. In a more recent paper, Allen alongside Schneider and Murphy pointed out that extending Schneider’s analysis to Latin America where “family sizes were likely larger (…) than in England and British North America” would amplify the wage gap between the two regions.

The table above shows how much family size varied around the late 17th century across region. Clearly, this is a non-negligible issue.

Sensitivity of estimates

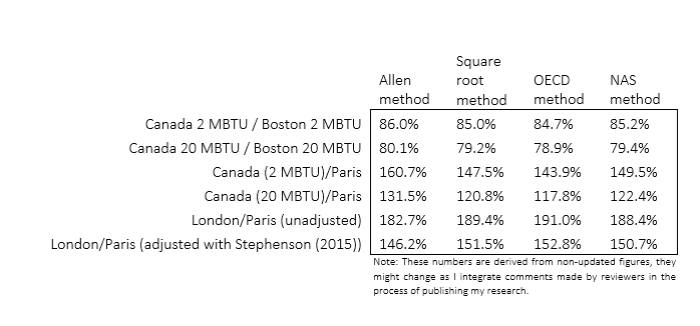

Just to see how much these points matter, let’s modify for two easily modifiable factors: household size (given the numbers above) and fuel requirements (calories from food are harder to adjust for and I am still in the process of doing that). Let’s recompute the welfare ratios (those classified as bare bones) of Canada (the outlier) relative to the other according to different changes circa the end of the 17th century. How much does it matter?

Comparing New World places like Canada and Boston does not change much – they are more or less similar (family size and relative price-wise). However, just adjusting for family size eliminates a quarter of the gap between Canada and Paris (from 61% to somewhere 43.9% and 49.5%). Then, the adjustment for the fact that it is freezing cold in Canada eliminates a little more than half the advantage Canada enjoyed. So roughly two third of the Canadian advantage over Paris (the richest place in France) is eliminated by adjusting for family size and fuel consumption without adjusting for food requirements. However, family size does not affect dramatically the comparison between Paris and London (regardless of whether we use the Allen figures or the Stephenson-Adjusted figures). Thus, most of the sensitivity issues are related to comparing the New World with the Old World.

Still, there are some appreciable differences from family structures within Europe (i.e. the Old World) that may alter the relative positions. For example, Ireland had much larger families than England in the 18th century (see here – the authors shared their dataset with me and a co-author): in 1700, England & Wales had an average household size of 4.7 compared with 5.32 in Ireland. That would moderately disrupt the comparison. Not as much as comparison between the New World and Old World, but enough to make cautious about European differences.

Conclusion

I have seen many discussions regarding the sensitivity of welfare ratios in numerous papers. I am not attempting to make my present point into some form of revolutionary issue. However, all the sensitivity estimates were concentrated on a case or another and they all concern a specific problem. No one has gathered all the problems in one place and provided a “range of estimates”. Maybe its time to go in that direction so that we know which place was poor and which was not (relative to one another, since anything preindustrial was basically dirt-poor by our modern standards).