- Making economic predictions is useless Branko Milanovic, globalinequality

- In praise of “austerity” Alberto Alesina, City Journal

- Suicidal tendencies Irfan Khawaja, Policy of Truth

- The study of history, strategic culture, and geopolitical conflict still matters Francis Sempa, ARB

Cyclical History

An interesting result from behavioral/experimental economics is that bubbles can happen even with smart people who should know better. But once those people go through a bubble, they do a better job of avoiding bubbles in the future.

I think this result has major implications for society more broadly and I think we’re seeing it play out in the news. In the ’70s people learned a lot of hard lessons about things like stagflation (and racism–but ask a sociologist about that) that made the following decades easier. But those people gradually retired and were replaced with people who weren’t inoculated to certain ideas (like the idea of inflating your way out of a supply-side recession).

We’re now living in a world where the median voter and her elected representatives have unlearned those hard lessons. And so we’re going to live through the 1970’s again. Hopefully. If we’re not so lucky we might live through the 1930’s again.

Nightcap

- Public and private pleasures (the coffeehouse) Phil Withington, History Today

- The historical state and economic development in Vietnam Dell, Lane, & Querubin, Econometrica

- The liberal world order was built with blood Vincent Blevins, New York Times

- Bowling alone with robots Kori Schake, War on the Rocks

Nightcap

- On the new conservative movement in the United States C Bradley Thompson, American Mind

- The sense of shame and the politics of humiliation Thomas Laqueur, Literary Review

- Money, modern life, and the city Daniel Lopez, Aeon

- Space exploration, and comparative coranavirus lockdowns Scott Sumner, MoneyIllusion

Nightcap

- Alesina was one of the most creative economists of his time Guido Tabellini, Il Foglio

- Alberto Alesina. A free-spirited economist Papaioannou & Stantcheva, VOXEU

- “Nation-Building, Nationalism, and Wars” Alesina, Reich, & Riboni, NBER

- The case against Mars Byron Williston, Boston Review

Broken incentives in medical research

Last week, I sat down with Scott Johnson of the Device Alliance to discuss how medical research is communicated only through archaic and disorganized methods, and how the root of this is the “economy” of Impact Factor, citations, and tenure-seeking as opposed to an exercise in scientific communication.

We also discussed a vision of the future of medical publishing, where the basic method of communicating knowledge was no longer uploading a PDF but contributing structured data to a living, growing database.

You can listen here: https://www.devicealliance.org/medtech_radio_podcast/

As background, I recommend the recent work by Patrick Collison and Tyler Cowen on broken incentives in medical research funding (as opposed to publishing), as I think their research on funding shows that a great slow-down in medical innovation has resulted from systematic errors in organizing knowledge gathering. Mark Zuckerberg actually interviewed them about it here: https://conversationswithtyler.com/episodes/mark-zuckerberg-interviews-patrick-collison-and-tyler-cowen/.

Nightcap

- The humbling of Dominic Cummings Harry Lambert, New Statesman

- Pandemic futarchy design Robin Hanson, Overcoming Bias

- Quite the IR controversy has broken out Jarrod Hayes, Duck of Minerva

- Republics, Extended and Multicultural William Voegeli, Claremont Review of Books

Nightcap

- The optimistic case for Hong Kong Anka Lee, Politico

- Taking political and economic frictions seriously Kevin Bryan, A Fine Theorem

- Patriarchy, fascism, and Dominic Cummings Maria Farrell, Crooked Timber

- Manga Soviet Union World War II Bunna Takizawa, Asahi Shimbun

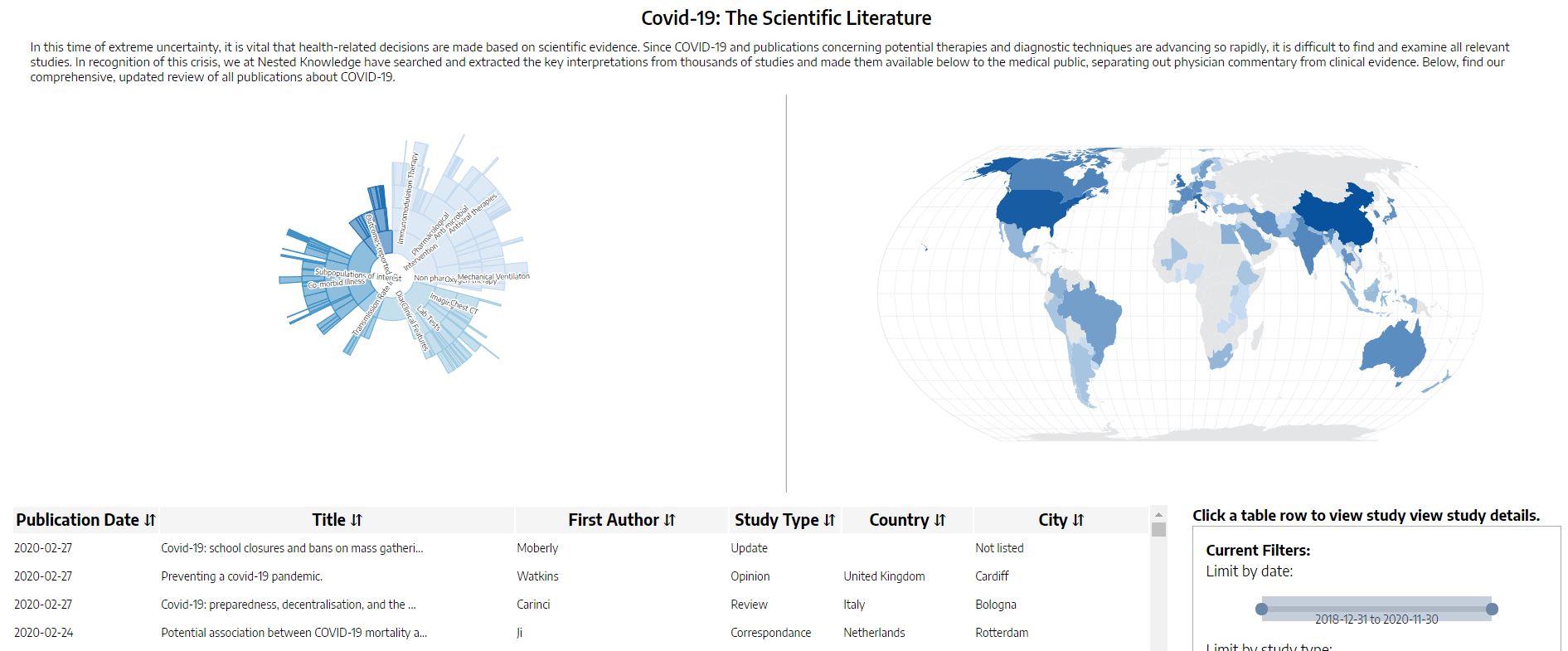

Launching our COVID-19 visualization

I know everyone is buried in COVID-19 news, updates, and theories. To me, that makes it difficult to cut through the opinions and see the evidence that should actually guide physicians, policymakers, and the public.

To me, the most important thing is the ability to find the answer to my research question easily and to know that this answer is reasonably complete and evidence-driven. That means getting organized access to the scientific literature. Many sources (including a National Library of Medicine database) present thousands of articles, but the organization is the piece that is missing.

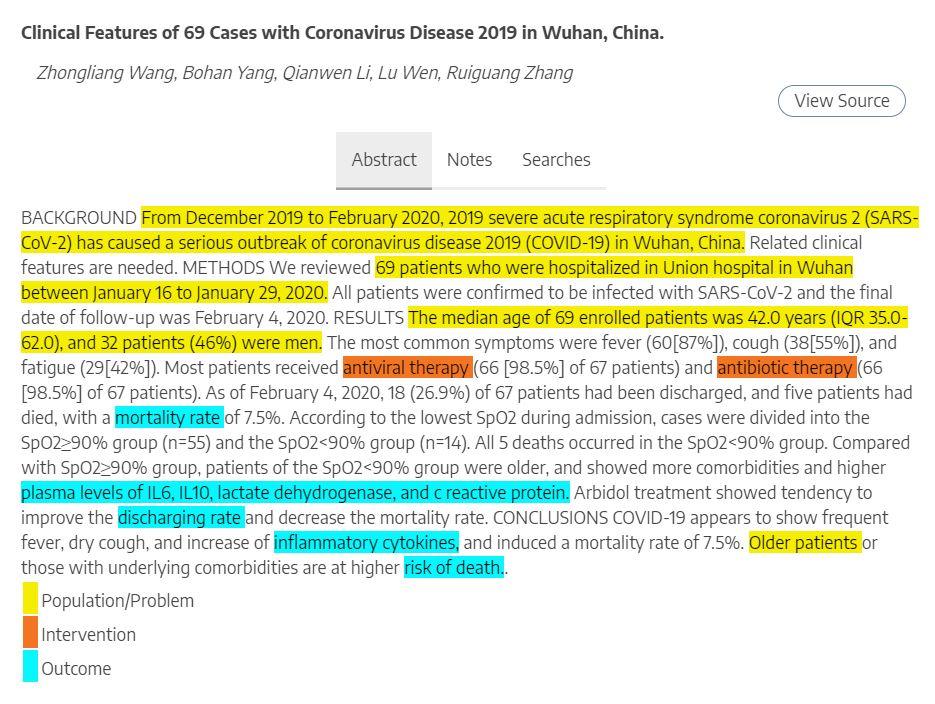

That is why I launched StudyViz, a new product that enables physicians to build an updatable visualization of all studies related to a topic of interest. Then, my physician collaborators built just such a visual for COVID-19 research, presenting a sunburst diagram that users can select to identify their research question of interest.

For instance, if you are interested in the impact of COVID-19 on pregnant patients, just go to “Subpopulations” and find “Pregnancy” (or neonates, if that is your concern). We nested the tags so that you can “drill down” on your question, and so that related concepts are close to each other. Then, to view the studies themselves, just click on them to see an abstract with the key info (patients, interventions, and outcomes) highlighted:

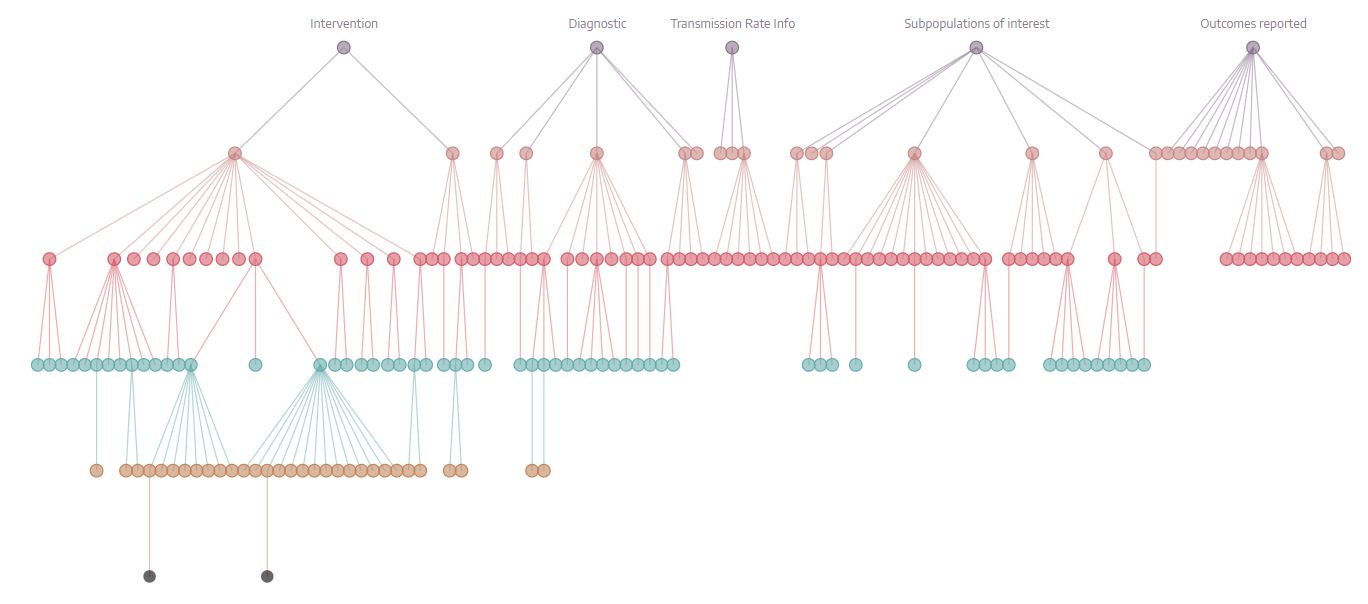

This is based on a complex concept hierarchy built by our collaborators and that is constantly evolving as the literature does:

Even beyond that, we opened up our software to let any researchers who are interested build similar visuals on any disease state, as COVID-19 is not the only disease for which organizing and accessing the scientific literature is important!

We are seeking medical coinvestigators–any physician interested in working with us, simply email contact@nested-knowledge.com or contact us on our website!

Pathologies in higher education: a book, a review, and a comment

Cracks in the Ivory Tower, by Jason Brennan and Phillip Magness, brings a much needed discussion of the pathologies of US higher education to the table. Brennan and Magness are two well-known classical liberals with a strong record of thoughtful interaction with Public Choice political economy.

Public Choice is an application of mainstream economic concepts to political situations. One of the key points of Public Choice is that people are self-interested and rational. This drives the choices they make. But people also act within formal and informal institutional environments. This constrains and enables some of their choices to a large degree. In other words, people react to incentives.

The Public Choice approach is not so much a normative handbook, but rather an attempt to explain how politics operate. The application of this theory to understand higher education in the US is a welcome addition to a growing literature on the economics of higher education.

It is perhaps surprising how the subtitle of the book stresses an aspect that tends to be extraneous to Public Choice scholarship: “The Moral Mess of Higher Education”. Of course we all draw on moral reasoning and assumptions in order to pass judgment on economic and political phenomena, but normally the descriptive side is kept separate – at least by economists – from explicit value judgment.

John Staddon, from Duke University, has reviewed Brennan’s and Magness’ book. In his review, he focuses on three main key issues. First, colleges and universities act on distorted incentives created, for example, by college rankings, to recruit students in ways that are not necessarily related to maintaining or expanding the academic prestige of the institution.

Second, teaching in higher education, at least in the US, is poorly evaluated. Historically, it has shifted from student evaluation to administrative assessment.

So why the shift from student-run to administration-enforced? And why did faculty agree to give these mandated evaluations to their students? Faculty acquiescence — naiveté — is relatively easy to understand. Who can object to more information? Who can object to a new, formal system that is bound to be more accurate than any informal student-run one? And besides, for most faculty at elite schools, research, not teaching, is the driver. Faculty often just care less about teaching; some may even regard it as a chore.

The incentives for college administrations are much clearer. Informal, student-run evaluations are assumed to be unreliable, hence cannot be used to evaluate faculty for tenure and promotion. But once the process is formalized, mandatory, and supposedly valid, it becomes a useful disciplinary tool, a way for administrators to control faculty, especially junior and untenured faculty.

This is not necessarily conducive to improvement in the quality of teaching. Perhaps colleges fare better than universities here, given that their faculty is not expected to allocate a large amount of hours per week to research and writing.

Third, Brennan and Magness offer a critique of what is known in the US system as “general education” courses. In their view, it is clear that those courses are unhelpful in a world where academic disciplines are increasingly more specialized. However, offering those courses is a good excuse for universities to grab more money from the students.

This is where Staddon begs to differ:

Cracks in the Ivory Tower usefully emphasizes the economic costs and benefits of university practices. But absent from the book is any consideration of the intrinsic value of the academic endeavor. Remaining is a vacuum that is filled by two things: the university as a business; and the university as a social activist. Both are destructive of the proper purpose of a university.

I tend to agree with this point, and I do not think it is a minor point. We can do colleges and universities without football, without gigantic administrative bureaucracies, and without the gimmicks to game the college ranking system. I could even go further and argue that we should do colleges and universities without dorms and an artificial second and worse version of teenage years right when students are supposed and expected to behave like adults. Getting rid of those tangential features of US higher education should help refocus on knowledge and reduce the cost.

Colleges and universities in the US are also expensive and unnecessarily inflated because of the structure of the student loans system, which also generates perverse incentives. But this point has been explained and described to exhaustion in the economic literature. This also has to change.

However, I am not convinced that making universities focus on professionalizing their students would be the best way to go. Brennan and Magness raise some important issues and concerns, some of which also apply outside the US, but the Staddon highlights in his review an important counterpoint: higher education, at least on the undergraduate level, shouldn’t be seen 100% as an investment good, but also as a consumer good:

Higher education does not exist for economic reasons. It exists (in the famous words of Matthew Arnold) to transmit “the best that has been thought and said,” in other words the ‘high culture’ of our civilization. Job-related, practical training is not unimportant. Universities, and much else of society, could not exist without a functioning economy. But — and this point is increasingly ignored on the modern campus and by the authors of CIT — these things are not the purpose, the telos if you like, of a university.

Undergraduate education is there to hand over knowledge to the next generation. It can be small and cheap. You need an adequate building, a small library with the best classic books, electronic access to journals, and faculty that excels at teaching. Courses would be general, comprehensive, and interdisciplinary by definition. The program could last only three years. An optional additional year could be offered to those with an academic profile, where they could pursue more specialization as a bridge to graduate education.

This is more or less the mediaeval model. I am not sure we need to reinvent the wheel in order to deal with the crisis of higher education. What we need is to get back on track – back to the bread and butter of college education. This is a reflection that both sides of the story – those who demand education and those that offer it – need to make.

Read more:

In a recent contribution to Notes on Liberty, Mary Lucia Darst has recently commented on the status of higher education during the 2020 pandemic and prospects for the future.

I also wrote about the college trap in the US a few years ago.

Nightcap (again)

(Ooops, lol. I hope all of NOL‘s American readers had a good Memorial Day, and that everybody else had a good Monday. The Glasner piece is an excellent discussion of the Austrian School of Economics.)

- An Austrian (School) tragedy David Glasner, Uneasy Money

Nightcap

- An Austrian (School) tragedy David Glasner, Uneasy Money

Nightcap

- The surprising lexical history of infectious disease Charles McNamara, Commonweal

- Immigration and virologic hysteria Michael Agovino, Not Even Past

- Against scarcity Marilynne Robinson, NYRB

- Can we escape from information overload? Tom Lamont, 1843

Be Our Guest (Sunday Poetry): “Food & Drinks to Rats & Finks”

Our latest Be Our Guest post comes from poet N.D.Y. Romanfort, and it’s another poem. Once again I’m taking liberties in regards to Alex’s “Sunday Poetry” series and sharing Romanfort’s poem today. An excerpt:

Two-legg’d rodents have seized

the cherished eateries.

For these rats of great size

Mere food scraps aren’t the prize.

Please, read the rest. Enjoy. And if you’ve got something to say and no place to say it, Be Our Guest.

Nightcap

- Is Turkey moderating its foreign policy? Fehim Tastekin, Al-Monitor

- On Rudyard Kipling’s World War I-era book Lance Morrow, City Journal

- Habsburgs: The rise and fall of a world power John Adamson, Literary Review

- The end of the New World Order Ross Douthat, New York Times