One of these days Brandon’s going to kick me off this blog for posting notes that aren’t “on liberty.” But maybe he’s not looking. I’ll take a chance.

This piece is about energy and on second thought, it is relevant to libertarians. We need to know what we’re talking about when we enter into controversies on current topics like energy. Insights into how markets work are crucial, of course, but not sufficient. We should arm ourselves with a few facts and Lord knows, maybe even a little understanding of basic physics.

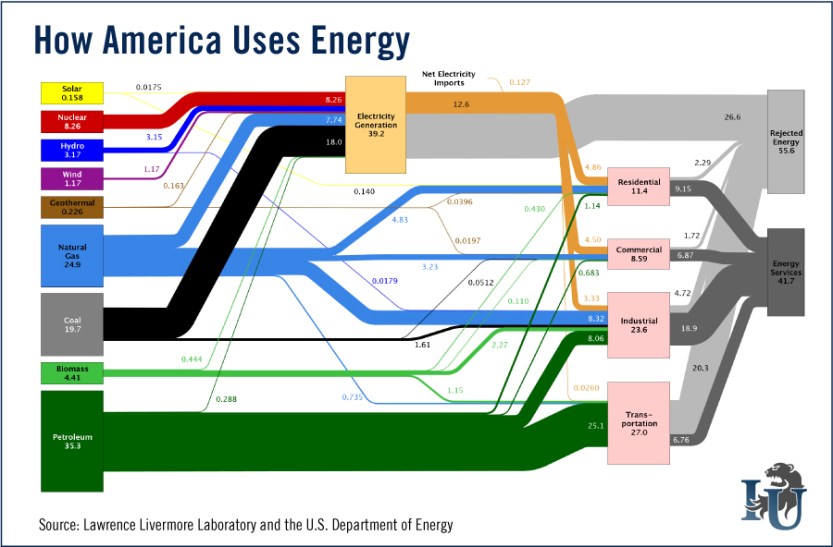

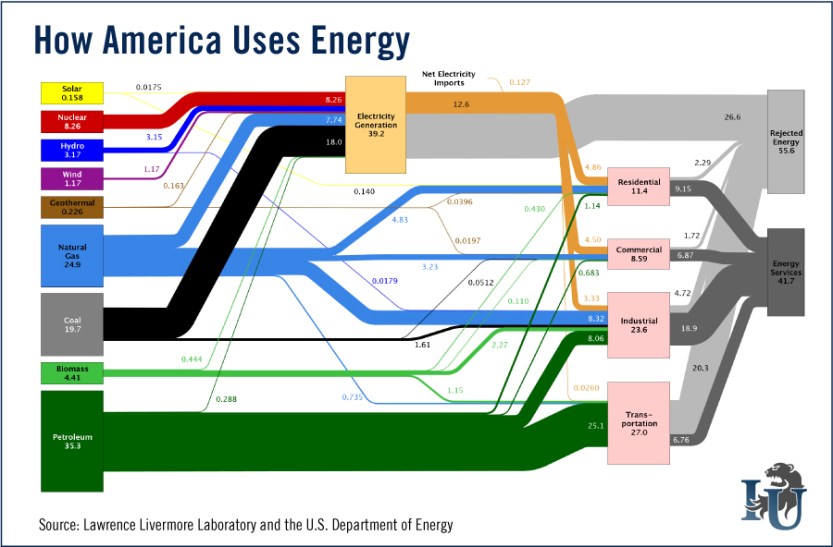

I base my remarks on an excellent chart produced by (gasp!) a government agency, Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory. It appears here but if it’s illegible please find a better copy here. Blame Brandon for squeezing our posts into a narrow column!

We see energy sources on the left. A couple of facts stand out. At the top, notice that solar and wind are negligible. The yellow line representing solar may be thinner than a single pixel on your monitor and therefore invisible. Geothermal is on the radar, but barely; same for biomass (wood chips, organic leftovers, corn used for ethanol instead of feeding people) that can either be burned or processed into methane or ethanol. Our three main sources are, and will be for the foreseeable future, petroleum, coal and natural gas.

At the top center we see electricity generation. We don’t consume electricity directly except maybe for executing criminals. We use it to power devices in the four broad categories shown on the right: residential, commercial, industrial, transportation.

Notice the fat grey line coming out of the electricity generation box called “rejected energy.” It tells us that about two thirds of the energy coming into power plants goes up in smoke or steam or other waste heat rather than electricity. That sounds like a terrible loss and indeed, there is always room for efficiency improvements at the margin. But, boys and girls, there’s something called the Second Law of Thermodynamics which puts an iron limit on how much energy in a particular situation is available to do useful work. In other words, a certain amount of the “waste” represented by that fat gray line is inevitable. It would be great if the good people at LLL could supply that calculation, but I suspect that reliable estimates of the necessary data would be difficult to come by.

Look at the residential box on the right. It only represents 11% of energy consumption meaning that relative to the big picture, home energy efficiency measures like insulation, solar panels, etc. can never do much for the big picture. I say this too keep things in perspective, not to deny the possibilities for cost-effective marginal improvements in many homes.

If your monitor resolution allows it, you’ll see a tiny orange line running from electricity generation to transportation. That means electric vehicles are, and for some time will be, utterly insignificant, though again, marginally beneficial in very special situations.

Another fat gray line comes out of transportation. When you burn gasoline, most of the energy goes out the tailpipe or the radiator; only a little ends up as kinetic energy and even that ends up as waste heat when you apply the brakes. (In the long run, it all ends up as waste heat. Look up “heat death” on Wikipedia.)

The overall message of this chart is: if we want to maintain anything like our present industrial civilization with its abundant heat/cooling, light, transportation, etc., we’d better keep the present main sources going – petroleum, coal, natural gas, nuclear because renewable energy sources are advancing only slowly and in many cases (wind and ethanol, especially), uneconomically. The stakes couldn’t be higher – significant losses of energy, more than anything short of nuclear war, will make life nastier, more brutish, and shorter.

How to decide which energy R&D projects deserve scarce resources? Solyndra, anyone? No, central planning of energy is just as much a disaster as any other form of central planning or maybe more so. Energy is a highly specialized field. A biomass expert, for example, may be ignorant of nuclear fusion. A transformer guy may know nothing of transmission line losses. I suspect there are dozens or hundreds of subspecialties within the biomass field. Knowledge, as Hayek taught us, is dispersed and often tacit. We need to let all these specialists use their particular knowledge and facilities to experiment around the edges, comparing present or expected future marginal costs and benefits. Other than an occasional nice chart like you see here, the Energy Department just gets in the way. (To see a boondoggle that dwarfs Solydra, google “national ignition facility.”)

Speaking of costs and benefits, one of these days I’ll comment on the strange notion that energy accounting – a perfectly legitimate engineering practice – should be used to judge the economic value of energy projects. Tallies of income/expenses and assets/liabilities, should, say proponents, be carried out not in dollars but in energy units (joules or BTUs.) Why is this wrong? Because the economic value of a joule depends on time and place and most critically, people’s ability to make good use of it. In fact, natural resources aren’t resources at all until and unless someone figures out how to make good use of them. More generally, value never inheres in physical objects and materials but only in the minds of people who believe those objects and materials can help satisfy wants, theirs or others’.

Postscript: The oceans store unimaginable amounts of thermal energy. You can calculate this yourself: using your favorite system of units, just multiply the volume of water by its mass density by its specific heat at constant pressure. You’ll discover that if we were willing to lower the ocean temperature by a thousandth of a degree per year, we would have abundant energy from now till Kingdom Come. Try this idea on a “progressive” friend sometime, keeping the answer momentarily in your back pocket: the Second Law forbids it. Stated differently, even with perfect technology, you would have to put more energy into the conversion process than the usable energy end product.