Past Friday, 51.9% of the British have voted to leave the European Union against 48.1% of those who have voted to remain. The details of the EU referendum can be found on BBC’s EU referendum page. Although it is still unclear what shape the relationship between Britain and the EU will take, I expect that the Brexit will offer good economic opportunities for Britain provided that they can reach free trade agreements with all nations within the EU and provided that they will continue to open up their markets for free trade with other countries outside of the EU.

An Exit of the Netherlands, or a Nexit, will have more consequences than a Brexit as the Netherlands are also participants in the European Monetary Union. A Nexit could therefore lead to an end of the Euro. An analysis of the EU is a political analysis and as politics is always complemented by power, this analysis should hence incorporate insights on power struggles and competing visions. Each country has its own interests within the EU, just like any politician within the EU has his own special interests that he is serving. Participation in the EU is often represented as an exercise of solidarity and political appeasement, however it is still politics with politicians’ usual desire for self-enrichment.

There have always been two competing visions of the EU. The first one is a classical liberal vision, led by German speaking Christian democrats Schuman (France), Adenauer (Germany) and Alcide de Gasperi (Italy) with the Treaty of Rome (1957) as the greatest achievement of this classical liberal vision for Europe. The Treaty sought to deliver the following four freedoms: free movement of goods, freedom of movement for workers, the right of establishment and freedom to provide services, and free movement of capital. The other vision was a socialist vision led by mainly French politicians, such as Jacques Delors and François Mitterrand whose goal was to create a supranational state.

Classical liberal vision

The first vision promotes political competition between the EU’s member states by opening up borders. When a person is discontent with the excessive taxes in his country, he could leave his country for another. Competition between member states would lead to smaller governments, lower taxes, and political respect for people who would want to pursue their individual freedoms in another member state. It would represent a return to the political model that was prevalent in Europe from the Middle Ages to the 19th century when different political systems coexisted independently. There were independent cities or city states in Flanders, Germany and Northern Italy. There was the kingdom of Bavaria, the republic of Venice, and small city states like Ghent and Bruges embraced their autonomy. The German writer and poet Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749-1832) had expressed the beauty of such a political system as follows when he discussed a Germany that was still splintered in 39 independent states:

“I do not fear that Germany will not be united; … she is united, because the German Taler and Groschen have the same value throughout the entire Empire, and because my suitcase can pass through all thirty-six states without being opened. … Germany is united in the areas of weights and measures, trade and migration, and a hundred similar things. … One is mistaken, however, if one thinks that Germany’s unity should be expressed in the form of one large capital city, and that this great city might benefit the masses in the same way that it might benefit the development of a few outstanding individuals. … What makes Germany great is her admirable popular culture, which has penetrated all parts of the Empire evenly. And is it not the many different princely residences from whence this culture springs and which are its bearers and curators? … Germany has twenty universities strewn out across the entire Empire, more than one hundred public libraries, and a similar number of art collections and natural museums; for every prince wanted to attract such beauty and good. Gymnasia, and technical and industrial schools exist in abundance; indeed, there is hardly a German village without its own school. … Furthermore, look at the number of German theaters, which exceeds seventy. … The appreciation of music and song and their performance is nowhere as prevalent as in Germany, … Then think about cities such as Dresden, Munich, Stuttgart, Kassel, Braunschweig, Hannover, and similar ones; think about the energy that these cities represent; think about the effects they have on neighboring provinces, and ask yourself, if all of this would exist, if such cities had not been the residences of princes for a long time. … Frankfurt, Bremen, Hamburg, Lübeck are large and brilliant, and their impact on the prosperity of Germany is incalculable. Yet, would they remain what they are if they were to lose their independence and be incorporated as provincial cities into one great German Empire? I have reason to doubt this.”[1]

In addition to the advancement of political competition, the vision also promotes economic competition. A German employee would not be obstructed from working in France anymore, a Dutchman would not be taxed by the government if he transfers money from a Dutch to a Spanish bank or when he decides to buy stocks on the Italian equity market. Nobody would withhold a Belgian brewery from selling beer in other countries within the European free trade area.

Socialist vision

The second vision promotes a European central state that holds the power to enact more regulations, redistribution of wealth, and harmonization of legal systems within the whole Union. A strong central political body is to coordinate such efforts. The consequence is that its member states would increasingly have to give up their sovereignty. This is clearly visible from the political events in Greece and Ireland during the financial crisis of 2008 when Brussels demanded from Greece and Ireland how they should deal with their deficits and what austerity measures they should take. The socialist vision of Europe is an ideal for the political class, bureaucrats, interest groups and the subsidized sectors that want a powerful central state for their self-enrichment. Political competition among its member states, something that the classical liberals supported, should be eliminated. Doing so, Europe becomes less democratic and political power is increasingly shifted into the hands of bureaucrats and technocrats in Brussels. Historically, such plans for concentrated political power had been realized by such figures as Charlemagne, Napoleon and Hitler. The difference with our times is that the creation of a modern European superstate does not directly require military means. The introduction of new institutes like the European Central Bank, a common currency like the Euro, and extended power of the European Commission would suffice. Similar socialist intentions were already visible from the start of the European integration in the European vision of Jean Monnet, the intellectual father of the European community. Fearing an independent and emerging Germany after the second World War, an integration of Germany into Europe was considered to be a good thing. Next to that, the French wanted to have control over the Rühr area and they wanted to keep other vital German resources out of solely German hands. After losing her colonial powers in Indochina and Africa, the French ruling elite were also looking for new influence and pride which they eventually found in the European community.[2] The French premier in 1950 had for example proposed a plan to install a European army under the leadership of the French.

Why it is good for the Netherlands to leave the European Union

I believe that the EU should never have had more ambitions than the free trade zone that requires no supranational institutes, except for a European Court of Justice that is restricted to supervising conflicts between the member states and guaranteeing the four freedoms. The EU has become so far removed from the classical liberal vision of political and economic competition that it is not worthwhile anymore for the Netherlands to participate. It has declined into a malignant cartel of states that can tell its members with whom and how they should conduct their trade. A good example were the quotas and import levies on Chinese solar panels in 2013 under the disguise of ‘anti-dumping’ measures. Several countries like the Netherlands and Germany had first opposed to these measures as they would like to maintain good relationships with China. Nonetheless, the European Committee, apparently under influence of solar panel lobbyists like those of the German producer Solarworld AG, introduced ‘anti-dumping’ measures. The eventual winners of such measures are European solar panel producers and its victims are the European people that simply want to buy cheap solar panels. Another example are the sanctions that the EU had imposed on Russia since the Ukrainian conflict – a conflict that was provoked by American imperialists and NATO.[3] The deteriorating trade relationships between the EU and Russia is also detrimental to the wealth of ordinary European citizens. Another recent example is the prohibition of high-powered vacuum cleaners and possible future bans on other energy appliances such as kettles and hairdryers in order to reach environmental targets.[4] Those who profit from such measures are mainly large legacy organizations such as Bosch and Siemens that have enough capital to meet the strict EU regulations.

Another reason why a Nexit would be good for the Netherlands is that it offers an opportunity to extricate oneself from the Euro and the implicitly pledged financial aid when a future financial crisis will tear through Europe.

The tragedy of the Euro

The introduction of the Euro has proven to be a huge mistake, because it has enabled fiscally irresponsible governments of such countries like Portugal, Italy, Greece, Spain etc. to conduct unsustainable economic policies. In the past, when these states had their own currency, their governments had to finance their budget deficits through the sales of government bonds which resulted in higher government debts. The higher government debts manifested itself in higher interest rates on their government bonds, and a greater money supply would lead to devaluations of their currencies.

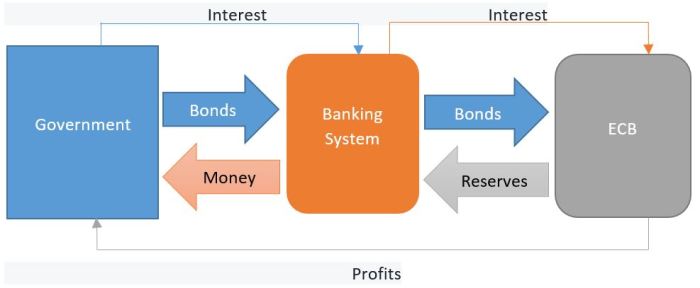

To illustrate how the process of government bonds financing works in the European Monetary Union, we could look at the development of 10-year government bonds. The graph below shows the interest rates that governments have to pay to the financiers of their 10-year government bonds from 1995 to 2011:

The y-axis represents the rates of interest that an investor receives from 10-year government bonds. Countries that are economically stronger and fiscally more conservative are rewarded with lower interest rates due to the smaller risk that these governments will not pay back their loans. In the case of Germany, a country with traditionally a stronger economy, a more conservative Bundesbank, and a fiscally more responsible government than many other European nations, investors received 7.5% interest on their 10-year government bonds in 1995. Greek government bonds had a yield of 18% in 1995. 1995 was the year in which the European Committee had announced that the Euro would arrive in 2002. Interest rates on government bonds consequently converged in the following years. At the end of 1997 all rates of interest on Portuguese, Irish, Spanish, Italian, French and German 10-year government bonds were more or less equal despite the fact that many of the governments of these countries still spent more than they received in tax incomes. The consequence of sharing a common currency with fiscally more responsible countries like Germany and the Netherlands is that fewer price signals in the form of higher interest rates on government bonds of fiscally irresponsible governments emerge. Irresponsible governments can issue government bonds to the banking sector that transfer these bonds as collateral to the ECB in return for loans. The interest rate that banks pay for the loans of the ECB are issued as profits to their governments. This is in short how ‘seigniorage’, the profits derived from money creation when the costs of money production and the distribution of money are lower than the value of money itself, is created.

This process leads to inflation, but the costs of inflation in the EMU are not solely borne by the respective country that issues the government bonds, but by all countries that participate in the EMU. A country like Spain can for example issue government bonds that traditionally would correspond with 10% inflation. However, when other countries like the Netherlands and Germany issue an amount of bonds that corresponds with 5% inflation, Spain benefits from seigniorage as the inflation created by Spain is higher and borne partly by the Netherlands and Germany. A Euro in this regard is beneficial for fiscally irresponsible governments. It is actually a “Tragedy of the commons”. Abusing the Euro in this way is exactly what countries like Portugal, Italy, Ireland, Greece, Spain and France have done. This works until a financial crisis shows how insolvent the governments of these countries actually are. That has happened in 2008, the moment when interest rates on European government bonds started diverging. The ECB had even decided to buy up Greek government debts in May 2010 in order to lower the interest rates on Greek government bonds. In June 2010, a temporary European Financial Stability Facility (EFSF) was founded with guarantees of up to €440 billion to combat the European sovereign debt crisis. It has provided financial assistance to Ireland, Portugal and Greece. The EFSF was later replaced by the European Stability Mechanism (ESM) in October 2012 with a total described capital of around €700 billion of which the Netherlands has pledged €40 billion in capital participation. The Dutch prime minister, Mark Rutte, had promised the Dutch in 2011 that the Netherlands would receive back the money it has loaned out to Greece in May 2010.[5] The total sum that was loaned to Greece by the Dutch was €3.2 billion. However, in 2012 when the Netherlands loaned out €14.5 billion of the second financial aid package of €130 billion that was pledged by Europe and the IMF to Greece, the Dutch minister of Finance, Jeroen Dijsselbloem, admitted that the Netherlands were losing money. Rutte also admitted that he could not guarantee that the Dutch loans to the Greeks would not be forgiven.[6] Three years later, on July 13 2015, the Netherlands loaned out another €22.6 billion to Greece.[7] It has become clear that such financial pledges of the Netherlands to fiscally irresponsible governments like that of Greece are not beneficial for the Dutch. Even in the long run it is not beneficial for the EU as it supports and prolongs a socialist European system that is deeply rotten to its core and destined to fail. What the EU needs is a radical return to decentralization and political competition.

The EU has become a sinking ship. It appears to me that the Netherlands should leave the Union as soon as possible. I do not see how Europe can maneuver itself safely through the next financial crisis that is at the point of breaking out as more banks are on the brink of collapse.[8] I also expect greater centralization of political power within the EU and a greater loss of individual member countries’ sovereignty. On June 27, 2016, the Polish media had reported that France and Germany were taking matters into their own hands and are using the Brexit to unveil their plan to morph the continent’s countries into one giant superstate. Under their radical proposals,

“EU countries will lose the right to have their own army, criminal law, taxation system or central bank, with all those powers being transferred to Brussels.”[9]

Conclusion

A sensible Netherlands would leave the European Union and the European Monetary Union in order to preserve political and economic sovereignty. They would have free trade agreements with all countries within and outside of the EU. EenVandaag, a popular Dutch TV programme, had published the results of their 27,000 large online poll on Sunday June 26, 2016 in which 54% of the Dutch would like to hold a referendum about the Netherlands’ participation in the EU. 48% of the poll wanted the Netherlands to leave the EU against 45% who would like to remain in the EU.[10] In the meantime, the Remain camp will continue their nauseating snobbery accusing the Leave camp of being racist, nationalistic, isolationist or simply ignorant.

References

Bagus, P. (2010). The Tragedy of the Euro.

BBC. (2016). EU referendum: The result in maps and charts.

China Courant. (2014). Mogelijk nieuwe straffen voor producenten Chinese zonnepanelen.

Dijkstra, M. (2015). Griekse crisis: wat heeft het allemaal gekost?

DutchNews.nl. (2016). Dutch PM rejects referendum calls: not in the Netherlands’ interest.

Fullfact.org. (2016). First they came for the vacuum cleaners: will it be kettles next?

Gutteridge, N. (2016). European SUPERSTATE to be unveiled: EU nations ‘to be morphed into one’ post-Brexit.

Hoppe, H.H. (2001). Democracy the god that failed.

Judt, T. (2006). Postwar: A History of Europe Since 1945.

McMurtry, J. (2016). Ukraine, America’s “Lebensraum”. Is Washington prepared to wage war on Russia?

NOS. (2011). Rutte verwacht Grieks geld terug.

NU.nl. (2012). Rutte geeft verbreken verkiezingsbelofte toe.

Zerohedge.com. (2016). Deutsche Bank tumbles near record lows as yield curve crashes.

Footnotes

[1] From Johann Peter Eckermann’s Conversations with Goethe (1836-1848).

[2] Tony Judt writes in Postwar: A History of Europe Since 1945 (2006) that “[U]nhappy and frustrated at being reduced to the least of the great powers, France had embarked upon a novel vocation as the initiator of a new Europe” (p. 153). He also writes that “[F]or Charles de Gaulle, the lesson of the twentieth century was that France could only hope to recover its lost glories by investing in the European project and shaping it into the service of French goals (p. 292).”

[3] See for example Prof. John McMurtry’s “Ukraine, America’s ‘Lebensraum’. Is Washington prepared to wage war on Russia?” for an analysis how Washington had provoked the Ukrainian conflict with Russia.

[4] See “First they came for the vacuum cleaners: will it be kettles next?”

[5] See “Rutte verwacht Grieks geld terug” (2011). http://nos.nl/artikel/275035-rutte-verwacht-grieks-geld-terug.html

[6] See “Rutte geeft verbreken verkiezingsbelofte toe” (2012). http://www.nu.nl/algemeen/2968363/rutte-geeft-verbreken-verkiezingsbelofte-toe.html

[7] See “Griekse crisis: wat heeft het ons allemaal gekost?” http://www.elsevier.nl/economie/article/2015/07/griekse-crisis-wat-heeft-het-ons-allemaal-gekost-2657386W/

[8] See for example “Deutsche Bank tumbles near record lows as yield curve crashes.” http://www.zerohedge.com/news/2016-06-13/deutsche-bank-tumbles-near-record-lows-yield-curve-crashes

[9] See “European SUPERSTAT to be unveiled: EU nations ‘to be morphed into one’ post-Brexit.” http://www.express.co.uk/news/politics/683739/EU-referendum-German-French-European-superstate-Brexit

[10] See “Dutch PM rejects referendum calls: not in the Netherlands’ interest.” http://www.dutchnews.nl/news/archives/2016/06/92520-2/