Sweden’s Imaginary Socialism as a Non-Model

Part One of this essay was posted a couple of days ago. In it, I reviewed some of the avatars and zombies of the vague words “socialist” and “socialism.” I arrived at the inescapable conclusion that Sen. Sanders “democratic socialism” means only Scandinavian and, specifically, Swedish “socialism.” I look at that social and fiscal arrangement below.

First, let me say that Sweden is a good place to live; it’s a very civilized country. I just don’t know in what sense it’s “socialist.” Center-left parties took part in governing the country for most of the 20th century, true. Yet, little of Swedish commerce or industry is nationalized, or in any way public property. The Swedish government tends not to be invasive with regulations or direct intervention. Sweden even ranks a little higher than the US in “business freedom” on the 2016 (international) Index of Economic Freedom. Swedish companies are thriving, at home and abroad. Swedish capitalism is obviously alive and well.

I suspect that what confused Sen. Sanders and those of his supporters who have even thought about it is that the Swedish government offers extensive and high quality services to its citizens, many of which services that would belong to the private sector in other advanced societies. Let me say it again because this is an important point: The Swedish government is a quality service provider. But Swedes pay for these services with very high taxes. Swedish workers, on the average receive less than 50 of the income they earn. Careful: micro aggression coming. This is to me an unbearable negation of personal freedom, no matter how high the quality of services Swedish citizens receive “in return.”

Thus, even in moderate, impeccably democratic Sweden, “socialism” proves to be liberticide, it blocks on a massive scale and routinely the realization of individual wishes, the pursuit of happiness, in other words. To take an example: Those Swedes who would rather earn less money and spend more time reading philosophy, for example, practically are prevented by high taxes from even trying lest they starve. Incidentally, the share of GDP taken by Swedish taxes has been declining since the 90s. It would make sense for socialist Sen. Sanders to ask why. Hint: This decline was accompanied by a strong rise in GDP growth.

Sweden is a well managed capitalist welfare state. It would have been more ingenuous for Sen. Sanders to say this clearly rather than drag out the soiled word “socialism.” This assumes that he knows the difference, of course. His followers evidently do not.

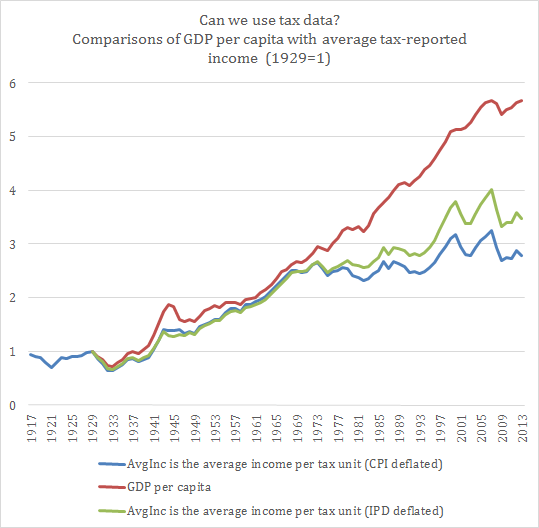

I want to make a detour here about Swedish income inequality because inequality is a topic dear to Sen. Sanders’ supporters. As you would expect, and as is intended, Sweden has one of the lowest income inequality on Earth (Gini Index: 0.25 vs the US about 0.44). However, its wealth inequality is very high (Gini Index: 0.85). This curious divergence is compatible with several scenarios including this alluring possibility: Socialist-inspired schemes designed to procure income equality had the effect – probably unintended – of freezing wealth disparities to where they were before “socialism.” It’s almost impossible to get ahead from near the bottom of the economic ladder when your income is seized before you even see it. For one thing, high taxes make it difficult or impossible to accumulate capital to create a new small business and therefore, new jobs. In other words, in many years of Swedish socialism, the restaurant waiter remained a restaurant waiter, the local Rockefeller remained Rockefeller, while the former was earning $12/hour and the latter only $24 (figures made up). As I said, other scenarios can account for divergence between income inequality and wealth inequality. Play at imagining them. Good luck.

Whether or not one considers the objectives of Swedish-style “democratic socialism” desirable, there are considerable obstacles in the path of realizing it in America. Sen. Sanders and his followers semi-consciously assume that given the right legislation – not to forget far-reaching executive orders since the path has been open by President Obama – the United States could be turned into a kind of Sweden. There are three-plus things about American society that make this dream unrealistic.

First, until right now, Sweden was a thoroughly middle-class society. I mean by this that nearly everyone, except for a few skinheads, shared an understanding of the good life, and the same ethical system. We, in the USA, by contrast have a whole Third World inside our boundaries. I refer, of course, to all of Louisiana, to Chicago and its suburbs, to some parts of Texas and New Mexico, and to nearly all black inner-city ghettos. (Read carefully: I did not say “predominantly black areas.”) Third World conditions breed predatory behavior. That makes the job of civil servants difficult. It also sucks up public resources for policing.

Second, and at the risk of breaching the etiquette of political correctness, Swedish society if fairly restrained as compared to most others, certainly as compared to American society. It’s a collective trait. It does not mean that most Swedes are restrained but that many Swedes are. I mean by this, for example, that on the average Swedish drunks are more polite, less noisy and less dangerous than American drunks. Collective restraint makes all government functions easier to perform obviously.

Third, Sen. Sanders assumes implicitly that given a victory, his administration would easily generate the first-class federal civil service that makes the Swedish welfare state function effectively and smoothly. That is an unrealistic assumption. Think the IRS, of course, and TSA (that’s never caught a terrorist ever, or ever stopped a terrorist action). Think of the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives that generously donated hundred of firearms to Mexican drug cartels. Think of the Environmental Protection Agency that declared CO2 – the main plant food – a noxious gas subject to its regulation. I could go on.

Good civil services are rooted in a broad social tradition whereas smart, well-educated people chose careers in government in preference to a business career. There is no such American tradition. It would take many years of bad private employment before preferences of such individuals would shift away from business. Here is the question: can so-called “socialist” policies be implemented so quickly in America that private employment will worsen soon enough to serve the requirements of a quality civil service necessary to the implementation of the same-self “socialism”?

I must add a fourth obstacle to the success of Swedish style welfare state in the US, one that I don’t necessarily believe in myself. Swedes and also Danes keep telling me the following: Their form of welfare “socialism” involves a high degree of forced sharing. The acceptance of such taking from Peter to give to Paul is well served by the fact that Paul is a lot like Peter and even looks a lot like him. According to this view, the high population homogeneity of Sweden until now is a necessary condition to the confiscatory taxes imposed on ordinary wage earners that is at the heart of its “socialism.” Needless to say, the US population is low on homogeneity (a fact I celebrate myself).

So, a gifted, honest, competent civil service is central to the welfare capitalist supposedly “socialist” Swedish model (which the Swedes themselves explicitly do not propose as a model). My unavoidably subjective judgment is that a United States Sanderista civil service would, with some effort, with much reform, place somewhere between the French and the Brazilian. To think otherwise is the height of ignorant wishful thinking bordering on hubris.

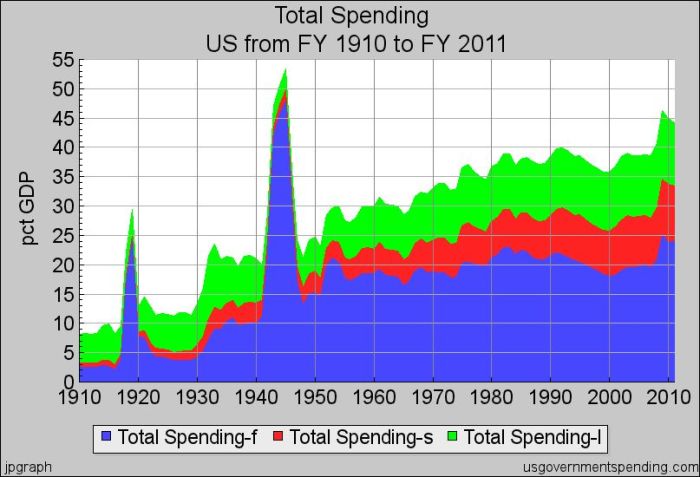

I am not hugely alarmed at the prospect of a new American capitalist welfarism though, for the simple reason that we are already half-way there. Sen. Sanders’ more-of-the-same would not be Armageddon. It only promises an accelerated decline of this vibrant, inventive, culturally brilliant society accompanied by more short-term equality, less equity, and more poverty- and therefore less freedom – for all.

PS Incidentally, I am not much opposed to Sen. Sanders’ proposal to make state universities and college tuition-free. I think the proposal has the same justification as publicly supported elementary and secondary schooling. I would be willing to bet such a measure would have the same overall beneficial economic results as the GI Bill did right after WWII. Finally, there is just a chance that government management would put a brake on the unconscionable rise in the cost of tertiary schooling, of what universities charge without restraints. It’s not as if the current system that largely separates the decision makers from the payers, from the beneficiaries, has worked really well!