- Rand Paul tests positive for coronavirus Bresnahan & Ferris, Politico

- The urgent lessons of World War I Brian Frydenborg, Modern War Institute

- Underestimating China Scott Sumner, MoneyIllusion

- Albania was not a True Communist country during the Cold War Griselda Qosja, Jacobin

coronavirus

Coronavirus and the BRI

The Corona Virus epidemic has shaken the world in numerous ways. The virus, which first emerged in the Chinese city of Wuhan (Hubei province), has led to the loss of over 12,000 lives globally. The three countries most impacted so far have been Italy (4,825 lives lost), China (3,287 lives lost), and Iran (1,500 lives lost) as of Saturday, March 21, 2020.

While there are reports that China is limping back to normalcy, the overall outlook for the economy is grim, to say the least, with some forecasts clearly predicting that even with aggressive stimulus measures China may not be able to attain 3% growth this year.

The Chinese slow down could have an impact on the country’s ambitious Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). While China has been trying to send out a message that BRI will not be impacted excessively, the ground realities could be different given a number of factors.

One of the important, and more controversial, components of the BRI has been the $62 billion China Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), which has often been cited as a clear indicator of ‘Debt Trap Diplomacy’ (this, some analysts argue, is China’s way of increasing other country’s dependency on it, by providing loans for big ticket infrastructural projects, which ultimately lead to a rise in debts).

The US and multilateral organizations like the International Monetary Fund (IMF) have predictably questioned the project, but even in Pakistan many have questioned CPEC, including politicians, with most concerns revolving around its transparency and long-term economic implications. Yet the Imran Khan-led Pakistan Tehreek-E-Insaaf (PTI) government, and the previous Pakistan Muslim League (Nawaz) (PML-N) government, have given the project immense importance, arguing that it would be a game changer for the South Asian nation.

On more than one occasion, Beijing has assured Pakistan that CPEC will go ahead as planned with China’s Ambassador to Pakistan, Yao Jing, stating on numerous occasions that the project will not be hit in spite of the Corona Virus. Senior officials in the Imran Khan government, including the Railway Minister Sheikh Rashid Ahmed and Foreign Minister Shah Mehmood Qureshi, in an interview with the Global Times, stated that while in the short run Corona may have an impact on CPEC, in the long run there would be no significant impact.

Analysts in Pakistan however, doubt that there will be no impact, given the fact that a large number of Chinese workers who had left Pakistan are unlikely to return. Since February 2020, a number of reports have been predicting that the CPEC project is likely to be impacted significantly.

Similarly, in the cases of other countries too, there are likely to be significant problems with regard to the resource crunch in China as well as the fact that Chinese workers cannot travel. Not only is Beijing not in a position to send workers, but countries hit by COVID-19 themselves will not be in a position to get the project back on track immediately, as they will first have to deal with the consequences of the outbreak.

Some BRI projects which had begun to slow down even before the outbreak spread globally were in Indonesia and Bangladesh. In Indonesia, a high speed rail project connecting Jakarta with Bandung (estimated at $6 billion) has slowed down since the beginning of the year, and ever since the onset of the Corona Virus, skilled Chinese personnel have been prevented from going back to Indonesia. Bangladesh too has announced delays on the Payra Coal power plant in February 2020. As casualties arising out of the virus increase in Indonesia and other parts of Asia and Africa, the first priority for countries is to prevent the spread of the virus.

While it is true that Beijing would want to send a clear message of keeping its commitments, matching up to its earlier targets is not likely to be a mean task. Even before the outbreak, there were issues due to the terms and conditions of the project and a number of projects had to be renegotiated due to pressure from local populations.

What China has managed to do successfully is provide assistance for dealing with COVID-19. In response to a request for assistance from the Italian government, China has sent a group of 300 doctors and corona virus testing kits and ventilators. The founder of Ali Baba and one of Asia’s richest men, Jack Ma, has also taken the lead in providing assistance to countries in need. After announcing that he will send 500,000 coronavirus testing kits and 1 million masks to the United States, Ma pledged to donate more than 1 million kits to Africa on Monday March 17, 2020, and on March 21, 2020, in a tweet, the Chinese billionaire said that he would be donating emergency supplies to a number of South Asian and South East Asian countries — Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Cambodia, Laos, Maldives, Mongolia, Myanmar, Nepal, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka. The emergency supplies include 1.8 million masks, 210,000 test kits, 36,000 protective suits and ventilators, and thermometers.

China is bothered not just about it’s own economic gains from the BRI, but is also concerned about the long term interests of countries which have signed up for BRI.

The Corona Virus has shaken the whole world, not just China, and the immediate priority of most countries is to control the spread of the pandemic and minimize the number of casualties. Countries dependent upon China, especially those which have joined the BRI, are likely to be impacted. What remains to be seen is the degree to which BRI is affected, and how developing countries which have put high stakes on BRI related projects respond.

Nightcap

- Four types of labor and the epidemic Branko Milanovic, globalinequality

- Republicans, Democrats, and coronavirus Ronald Brownstein, Atlantic

- War with Iran: Regrets only Irfan Khawaja, Policy of Truth

- Taiwan’s robust constitutionalism and coronavirus Wen-Chen Chang, Verfassungsblog

Never reason from a fatality rate

Richard Epstein has produced several posts and a video interview arguing that the mainstream media is overreacting to the Coronavirus pandemic. Richard understands the potential seriousness of this situation and the proper role of government. He recognises the value of the Roman maxim Salus populi suprema lex esto – let the health of the people be the highest law. In public health emergencies, many moral and legal claims resulting from individual rights and contracts are vitiated, and some civil liberties suspended.

Nevertheless, along with Cass Sunstein, Richard claims that this particular emergency is likely to be overblown. His justification for this is based on data for infection and fatality rates emerging from South Korea and Singapore that appear (currently) under control with only a relatively small proportion of their population infected. This was achieved without the country-wide lockdowns now being rolled out across Europe. Extrapolating from this experience, Richard suggests that the Coronavirus is not too contagious outside particular clusters of vulnerable individuals in situations like cruise ships and nursing homes.

The line of argument is vulnerable to the same criticism that one should never reason from a price change. The classic case of reasoning from a price change is reading oil prices as a measure of economic health. When oil prices drop, it could herald an economic boom or, paradoxically, a recession. If the price dropped because supply increased, when OPEC fails to enforce a price floor, then that lower price should stimulate the rest of the economy as transport and travel become cheaper. But if the price drops because economic activity is already dropping, and oil suppliers are struggling to sell at high prices, then the economy is heading towards a recession. The same measure can mean the opposite depending on the underlying mechanism.

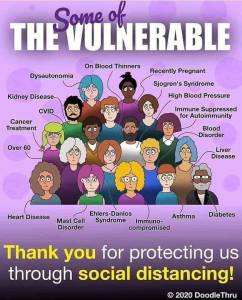

The same logic applies to epidemics. The transmission rate is a combination of the (potentially changing) qualities of the virus and the social environment in which it spreads. The social environment is determined, among other things, by social distancing and tracking. Substantial changes in lifestyle can have initially marginal, but day after day very large, impacts on the infection rate. When combined with the medium-term fixed capacity of existing health systems, those rates translate into the difference between 50,000 and 500,000 deaths. You can’t look at relatively low fatality rates in some specific cases to project rates elsewhere without understanding what caused them to be the rate they are.

Right now, we don’t know for sure if the infection is controllable in the long run. However, we now know that South Korea and Singapore controlled the spread so far and also had systems in place to test, track and quarantine carriers of the virus. We also now know that Italy, without such a system, has been overrun with serious cases and a tragic increase in deaths. We know that China, having suppressed knowledge and interventions to contain the virus for several months, got the virus under control only through aggressive lockdowns.

So the case studies, for the moment, suggest social distancing and contact tracing can reduce cases if applied very early on. But more draconian measures are the only response if testing isn’t immediately available and contact tracing fails. Now is sadly not the time for half-measures or complacency.

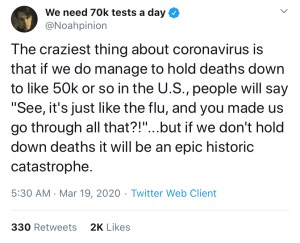

I believe that Richard’s estimated fatality rates (less than 50,000 fatalities in the US) are ultimately plausible, but optimistic at this stage. Perversely, they are only plausible at all insofar as people project a much higher future fatality rate now. People must act with counter-intuitively strong measures before there is clear and obvious evidence it is needed. Like steering a large ship, temporally distant sources of danger must prompt radical action now. We will be lucky if we feel like we did too much in a few months’ time. Richard believes people are more worried than warranted right now. I think that’s exactly how worried people need to be to adopt the kind of adaptive behaviors that Richard relies on to explain how the spread of infection will stabilise.

I stopped French kissing. (Coronavirus alert!)

About 40 US deaths so far. The French have double that with 1/5 the population. My skeptical fiber is on full. Still I am washing my hands. When I run out of rubbing alcohol, I will use cheap brandy – of which I have plenty, of course. Oh, I almost forgot: I have decided to stop French kissing completely if the occasion arises! Extraordinary times require extraordinary measures! Count on me. I am wondering what the libertarian response should be to this public crises (plural).

My best to all.

Coronavirus and takings

City governments are flirting with a ban on evictions during the coronavirus pandemic. I doubt, however, that doing so comports with the Constitution’s takings clause or, perhaps, the contracts clause.

San Jose has introduced legislation that will ban evictions due to un/underemployment resulting from coronavirus. Seattle’s socialist firebrand, Kshama Sawant, calls for similar action. Her letter, though, betrays the truth behind many proposed emergency measures–she’s leveraging the crisis to further her political agenda, particularly her hatred of capitalism. In the letter, she froths: “The status quo under capitalism is deeply hostile to the majority of working people, and it would be unconscionable to place the further burden of the Coronavirus crisis on those who are already the most economically stressed.” Never mind that the status quo in the absence of capitalism would be grinding poverty.

But, in any case, the proposal to ban evictions and force landlords to renew leases as the pandemic sweeps across the states raises serious constitutional concerns. Even in times of crisis, observance of constitutional norms remains essential. In part, this is because laws passed as emergency measures tend to hang about long after the emergency subsides. New York rent control began as a wartime measure, for instance, and that curse still plagues the New York rental market. The other reason, of course, is that the Constitution is built for just these moments. The pressure to invade rights, after all, comes when things are not going well. As Justice Sutherland once put it, “If the provisions of the Constitution be not upheld when they pinch, as well as when they comfort, they may as well be abandoned.”

Forcing landlords to either renew leases or forego eviction for lease violations likely raises at least two constitutional problems: takings and impairment of contractual obligations. While such laws don’t literally seize property, they effectively impose a servitude on landlords’ property, stripping them of control over the disposition and occupation of their land. When an essential attribute of property ownership is destroyed by regulation in this manner, the government must offer compensation. We already know this compensation requirement applies during national emergencies. During World War II, for instance, the Supreme Court held that the United States had to compensate property owners and leaseholders when it temporarily seized factories for wartime production.

The contract clause problem is also straightforward: barring landlords from enforcing lease terms impairs obligations under pre-existing contracts. The contracts clause, though, has been severely undermined in recent decades, such that a showing of a compelling interest like mitigating the impact of the pandemic may well satisfy the flaccid demands of the modern contracts clause.

It may seem profoundly harsh to impose constitutional constraints on governments trying to resolve a crisis. But three things ought to be kept in mind.

First, an emergency certainly means that some will face a heavy burden, but that fact tells us nothing about how that burden should be allocated. Why should landlords bear the costs? Indeed, As the Supreme Court said in Armstrong v. United States, the takings clause exists to avoid imposing societal burdens on specific individuals: “The Fifth Amendment’s guarantee that private property shall not be taken for a public use without just compensation was designed to bar Government from forcing some people alone to bear public burdens which, in all fairness and justice, should be borne by the public as a whole.”

Second, we should keep in mind that lease agreements already account for risk. That’s baked into the price and terms that give rise to a mutually agreeable arrangement between parties. To simply allow one party to slip out of the terms of the lease distorts that arrangement.

Third, the takings clause does not bar emergency measures, including the seizure of property, but only upon just compensation. No exigency should excuse cities like San Jose or Seattle from compensating for the costs they’re hoisting upon landlords. And in the case of the contracts clause, the government could still honor existing leases by acting as a guarantor for tenants who can’t pay the rent.

All of these points apply to a world in which landlords do not voluntarily exercise leniency. But I think we’ll find that most landlords are forgiving during a temporary crisis. Most landlords have an extreme aversion to evicting tenants–it’s the nightmare, last-ditch option that they try hard to avoid. That, plus the simple dose of compassion that many landlords will feel inspired to offer, may do more toward helping see us through than any emergency measures.