Note: This is the third in a series of essays on public discourse. Here’s Part 1 and Part 2

Three years ago, I started this essay series on the collapse of public discourse. At the time, I was frustrated by how left-wing and progressive spaces had become cognitively rigid, hostile, and uncharitable to any and all challenges to their orthodoxy. I still stand by most everything I said in those essays. Once you have successfully identified that your interlocutors are genuinely engaging in good faith, you must drop the soldier mindset that you are combating a barbarian who is going to destroy society and adopt a scout mindset. For discourse to serve any useful epistemic or political function, interlocutors must accept and practice something like Habermas’ rules of discourse or Grice’s maxims of discourse, where everyone is allowed to question or introduce any idea to cooperatively arrive at an intersubjective truth. The project of that previous essay was to therapeutically remind myself and any readers to actually apply and practice those rules of discourse in good-faith communication.

However, at the time, I should have more richly emphasized something that has been quite obviously true for some time now: most interlocutors in the political realm have little to no interest in discourse. I wish more people had such an interest, and still stand by the project of trying to get more people, particularly in leftist and libertarian spaces, to realize that when they speak to each other, they are not dealing with barbarian threats. However, recent events have made it clear that the real problem is figuring out when an interlocutor is worthy of having the rules of discourse applied in exchanges with them. Here is an obviously non-exhaustive list of such events in recent times that make this clear:

- The extent to which Trump himself, as well as his advisors and lawyers, engage in lazy, dishonest, and bad-faith rationalizations for naked, sadistic, unconstitutional executive power grabs.

- The takeover of the most politically influential social media by a fascist billionaire rent-seeker has resulted in a complete fragmentation and breakdown of the online public square.

- The degree to which most on the right and many on the left indulge in insane conspiracy theories, which have eroded and destroyed the epistemic norms of society, for reasons of rational irrationality.

- Even the Supreme Court, the institution that ostensibly is most committed to publicly justifying and engaging in good-faith reasoning about laws, is now giving blatantly awful, authoritarian opinions so out of step with their ostensibly originalist and/or textualist legal hermeneutics and constitutionalist principles (not to mention the opinions of even conservative judges in lower courts). It certainly seems the justices are just as nakedly corrupt and intellectually bankrupt as rabble-rousing aspiring autocrats. Indeed, the court is in such a decrepit state of personalist capture by an aspiring fascist dictator that they aren’t even attempting to publicly justify ‘shadow docket’ rulings in his favor. One can only conclude conservative justices are engaging in bad-faith power-grabs for themselves, whether they intend to or not. Although this has always been true of statist monocentric courts to some extent, recent events have only further eroded the court’s pretenses to being a politically

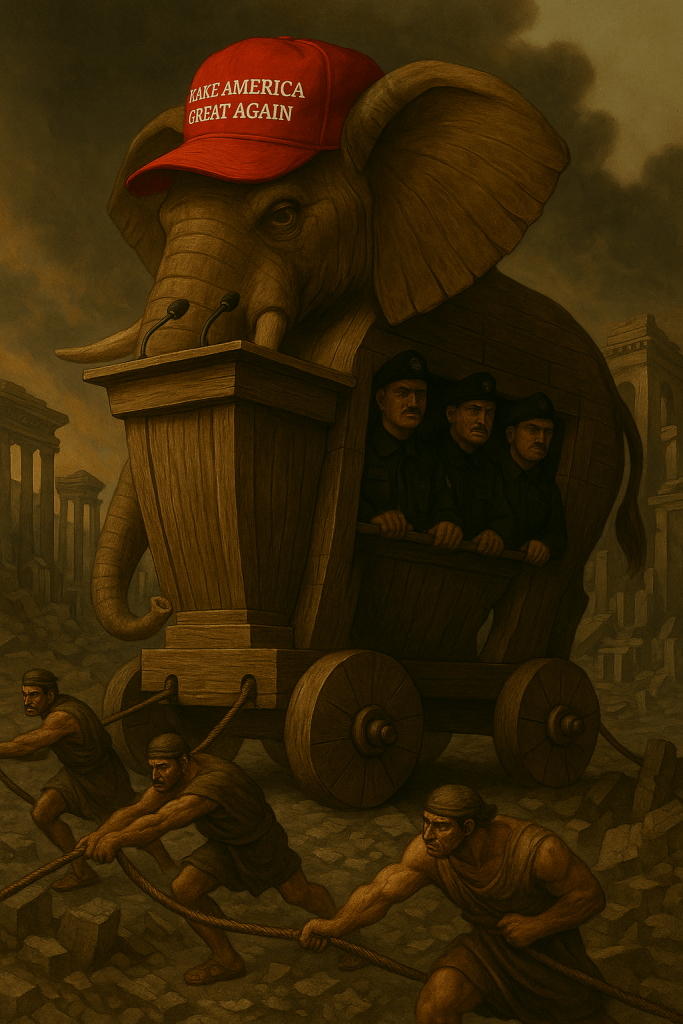

All these were obvious trends three years ago and have very predictably only gotten more severe. You may quibble with the extent of my assessment of any individual example above. Regardless, all but the most committed of Trumpanzees can agree that there is a time and place to become a bit dialogically illiberal in times like these. Thus, it is time to address how one can be a dialogical liberal when the barbarians truly are at the gates. The tough question to address now is this: what should the dialogical liberal do when faced with a real barbarian, and how does she know she is dealing with a barbarian?

This is an essay about how to remain a dialogical liberal when dialogical liberalism is being weaponized against you. This essay isn’t for the zealots or the trolls. It’s for those of us who believed, maybe still believe, that democracy depends on dialogue—but who are also haunted by the sense that this faith is being used against us.

Epistemically Exploitative Bullshit

I always intended to write an essay to correct the shortcomings of the original one. I regret that, for various personal reasons, I did not do so sooner. The sad truth is that a great many dialogical illiberals who are also substantively illiberal engage in esoteric communication (consciously or not). That is, their exoteric pretenses to civil, good-faith communication elide an esoteric will to domination. Sartre observed this phenomenon in the context of antisemitism, and he is worth quoting at length:

Never believe that anti‐Semites are completely unaware of the absurdity of their replies. They know that their remarks are frivolous, open to challenge. But they are amusing themselves, for it is their adversary who is obliged to use words responsibly, since he believes in words. The anti‐Semites have the right to play. They even like to play with discourse for, by giving ridiculous reasons, they discredit the seriousness of their interlocutors. They delight in acting in bad faith, since they seek not to persuade by sound argument but to intimidate and disconcert. If you press them too closely, they will abruptly fall silent, loftily indicating by some phrase that the time for argument is past. It is not that they are afraid of being convinced. They fear only to appear ridiculous or to prejudice by their embarrassment their hope of winning over some third person to their side.

If then, as we have been able to observe, the anti‐Semite is impervious to reason and to experience, it is not because his conviction is strong. Rather, his conviction is strong because he has chosen first of all to be impervious.

What Sartre says of antisemitism is true of illiberal authoritarians quite generally. Thomas Szanto has helpfully called this phenomenon “epistemically exploitative bullshit.”

One feature of epistemically exploitative bullshit that Szanto highlights is that epistemically exploitative bullshit need not be intentional. Indeed, as Sartre implies in the quote above, the ‘bad faith’ of the epistemically exploitative bullshitter involves a sort of self-deception that he may not even be consciously aware of. Indeed, most authoritarians (especially in the Trump era) are not sufficiently self-aware or intelligent enough to consciously realize that they are deceiving others about their attitude towards truth by spouting bullshit. As Henry Frankfurt observed, bullshit is different from lying in that the liar is intentionally misrepresenting the truth, but the bullshitter has no real concern for truth in the first place. Thus, many bullshiters (especially those engaged in epistemically exploitative bullshit) believe their own bullshit, often to their detriment.

However, the fact that epistemically exploitative bullshit is often unintentional, or at least not consciously intentional, creates a serious ineliminable epistemic problem for the dialogical liberal who seeks to combat it. It is quite difficult to publicly and demonstrably falsify the hypothesis that one’s interlocutor is engaging in epistemically exploitative bullshit. This often causes people who, in their heart of hearts, aspire to be epistemically virtuous dialogical liberals to misidentify their interlocutors as engaging in epistemically exploitative bullshit and contemptuously dismiss them. I, for one, have been guilty of this quite a bit in recent years, and I imagine any self-reflective reader will realize they have made this mistake as well. We will return to this epistemic difficulty in the next essay in this series.

To avoid this mistake, we must continually remind ourselves that the ascription of intention is sometimes a red herring. Epistemically exploitative bullshit is not just a problem because bullshitters intentionally weaponize it to destroy liberal democracies. It is a problem because of the social and (un)dialectical function that it plays in discourse rather than its psychological status as intentional or unintentional.

It is also worth remembering at this point that it is not just fire-breathing fascists who engage in epistemically exploitative bullshit. Many non-self-aware, not consciously political, perhaps even liberal, political actors spout epistemically exploitative bullshit as well. Consider the phenomenon of property owners—both wealthy landlords and middle-class suburbanites—who appeal to “neighborhood character” and environmental concerns to weaponize government policy for the end of protecting the economic rents they receive in the form of property values. Consider the similar phenomenon of many market incumbents, from tech CEOs in AI to healthcare executives and professionals, to sports team owners, to industrial unions, to large media companies, who all weaponize various seemingly plausible (and sometimes substantively true) economic arguments to capture the state’s regulatory apparatus. Consider how sugar, tobacco, and petrochemical companies all weaponized junk science on, respectively, obesity, cigarettes, and climate change to undermine efforts to curtail their economic activity. Almost none of these people are fire-breathing fascists, and many may believe their ideological bullshit is true and tell themselves they are helping the world by advancing their arguments.

The pervasive economic phenomenon of “bootleggers and Baptists” should remind us that an unintentional form of epistemically exploitative bullshit plays a crucial role in rent seeking all across the political spectrum. This form of bullshit is particularly hard to combat precisely because it is unintentional, but its lack of intentionality in no way lessens the harmful social and (un)dialectical functions it severe.

Despite those considerations, it is still worth distinguishing between consciously intentional forms of aggressive esotericism and more unintentional versions because they must be approached very differently. Unintentional bullshitters do not see themselves as dialogically illiberal. Therefore, responding to them with aggressive rhetorical flourishes that treat them contemptuously is very unlikely to be helpful. For this reason, the general (though defeasible) presumption that any given person spouting epistemically exploitative bullshit is not an enemy that I was trying to cultivate in the second part of this essay series still stands. In the next essay, I will address how we know when this presumption has been defeated. However, for now, let us turn our attention to the forms of epistemically exploitative bullshit common today on the right. We have now seen how epistemically exploitative bullshit can appear even in technocratic, liberal settings. But that phenomenon takes on a more virulent form when fused with authoritarian intent. This is what I call aggressive esotericism.

Aggressive Esotericism

The corrosiveness of these more ‘liberal’ and technocratic forms of epistemically exploitative bullshit discussed above, while serious, pales in comparison to more bombastically authoritarian forms of it. The truly authoritarian epistemically exploitative bullshiter aims at more than amassing wealth by capturing some limited area of state policy. While he also does that, the fascist aims at the more ambitious goal of dismantling democracy and seizing the entire apparatus of the state itself.

Let us name this more dangerous form of epistemically exploitative bullshit. Let us call this aggressive esotericism and loosely define it as the phenomenon of authoritarians weaponizing the superficial trappings of democratic conversation to elide their will to dominate others. This makes the fascistic, aggressive esotericist all the more cruel, destructive, and corrosive of society’s epistemic and political institutions.

It is worth briefly commenting on my choice of the words “aggressive esotericism” for this. The word “esoteric” in the way I am using it has its roots in Straussian scholars who argue that many philosophers in the Western tradition historically did not literally mean what their discursive prose appears to say. Esoteric here does not mean “strange,” but something closer to “hidden,” in contrast to the exoteric, surface-level meaning of the text. We need not concern ourselves with the fascinating and controversial question of whether Straussians are right to esoterically read the history of Western philosophy as they do. Instead, I am applying the general idea of a distinction between the surface level and deeper meaning of a text, the sociological problem of interpreting both the words and the deeds of certain very authoritarian political actors.

I choose the word “aggressive” to contrast with what Arthur Melzer calls “protective,” “pedagogical,” or “defensive” esotericism. In Philosophy Between the Lines Melzer argues that historically, philosophers often hid a deeper layer of meaning in their great texts. In the ancient world, Melzer argues, this was in part because they feared theoretical philosophical ideas could disintegrate social order (hence the “protective esotericism”), wanted their young students to learn how to come to philosophical truths themselves (hence the “pedagogical esotericism”), or else wanted to protect themselves from authorities for ‘corrupting the youth’ (as Socrates was accused) with their heterodox ideas.

As the modern world emerged during the Enlightenment, Melzer argues esotericism continued as philosophers such as John Locke wrote hidden messages not just for defensive reasons but to help foster liberating moral progress in society, as they had a far less pessimistic view about the role of theoretical philosophy in public life (hence their “political esotericism”). Whether Melzer is correct in his reading of the history of Western political thought need not concern us now. My claim is that many authoritarians (both right-wing Fascists and left-wing authoritarian Communists) invert this liberal Enlightenment political esotericism by engaging—both in words and in deeds, both consciously and subconsciously, and both intentionally and unintentionally—in aggressive esotericism. Hiding their esoteric will to domination behind a superficial façade of ‘rational’ argumentation.

Aggressive esotericism is a subset of the epistemically exploitative bullshit. While aggressive esotericism may be more often intentional than more technocratic forms of epistemically exploitative bullshit, it is not always so. You might realize this when you reflect on heated debates you may have had during Thanksgiving dinners with your committed Trumpist family members. Nonetheless, this lack of intention doesn’t cover up the fact that their wanton wallowing in motivated reasoning, rational ignorance, and rational irrationality has the selfish effect of empowering members of their ingroup over members of their outgroup. This directly parallels how the lack of self-awareness of the technocratic rentseeker ameliorates the dispersed economic costs on society.

Aggressive Esotericism and the Paradox of Tolerance

Even if one suspects one is encountering a true fascist, one should still have the defeasible presumption that they are a good-faith interlocutor. Nonetheless, fascists perniciously abuse this meta-discursive norm. This effect has been well-known since Popper labelled it the paradox of tolerance.

The paradox of tolerance has long been abused by dialogical illiberals on both the left and the right to undermine the ideas of free speech and toleration in an open society, legal and social norms like academic freedom and free speech, and to generally weaken the presumption of good faith we have been discussing. This, however, was far from Popper’s intention. It is worth revisiting Popper’s discussion of the Paradox of Tolerance in The Open Society and Its Enemies:

Unlimited tolerance must lead to the disappearance of tolerance. If we extend unlimited tolerance even to those who are intolerant, if we are not prepared to defend a tolerant society against the onslaught of the intolerant, then the tolerant will be destroyed, and tolerance with them. In this formulation, I do not imply, for instance, that we should always suppress the utterance of intolerant philosophies; as long as we can counter them by rational argument and keep them in check by public opinion, suppression would certainly be most unwise. But we should claim the right even to suppress them, for it may easily turn out that they are not prepared to meet us on the level of rational argument, but begin by denouncing all argument; they may forbid their followers to listen to anything as deceptive as rational argument, and teach them to answer arguments by the use of their fists. We should therefore claim, in the name of tolerance, the right not to tolerate the intolerant. We should claim that any movement preaching intolerance places itself outside the law, and we should consider incitement to intolerance and persecution as criminal, exactly as we should consider incitement to murder, or to kidnapping, or as we should consider incitement to the revival of the slave trade.

His point here is not so much to sanction State censorship of fascist ideas. Instead, his point is that there are limits to what should be tolerated. To translate this to our language earlier in the essay, he is just making the banal point that our presumption of good-faith discourse is, in fact, defeasible. The “right to tolerate the intolerant” need not manifest as legal restrictions on speech or the abandonment of norms like academic freedom. This is often a bad idea, given that state and administrative censorship creates a sort of Streisand effect that fascists can exploit by whining, “Help, help, I’m being repressed.” If you gun down the fascist messenger, you guarantee that he will be made into a saint. Further, censorship will just create a backlash as those who are not yet fully-committed Machiavellian fascists become tribally polarized against the ideas of liberal democracy. Even if Popper himself might not have been as resistant to state power as I am, there are good reasons not to use state power.

Instead, our “right to tolerate the intolerant” could be realized by fostering a strong, stigmergically evolved social stigma against fascist views. Rather than censorship, this stigma should be exercised by legally tolerating the fascists who spout their aggressively esoteric bullshit even while we strongly rebuke them. Cultivating this stigma includes not just strongly rebuking the epistemically exploitative bullshit ‘arguments’ fascists make, but exercising one’s own right to free speech and free association, reporting/exposing/boycotting those, and sentimental education with those the fascists are trying to target. Sometimes, it must include defensive violence against fascists when their epistemically exploitative bullshit manifests not just in words, but acts of aggression against their enemies.

The paradox of tolerance, as Popper saw, is not a rejection of good-faith dialogue but a recognition of its vulnerability. The fascists’ most devastating move is not to shout down discourse but to simulate it: to adopt its procedural trappings while emptying it of sincerity. What I call aggressive esotericism names this phenomenon. It is the strategic abuse of our meta-discursive presumption of good faith.

Therefore, one must be very careful to guard against mission creep in pursuing this stigmergic process of cultivating stigma in defense of toleration. As Nietzsche warned, we must be guarded against the danger that we become the monsters against whom we are fighting. I hope to discuss later in this essay series how many on the left have become such monsters. For now, let us just observe that this sort of non-state-based intolerant defense of toleration does not conceptually conflict with the defeasible presumption of good faith.

In the next part of this series, I turn to the harder question: when and how can a dialogical liberal justifiably conclude that an interlocutor is no longer operating in good faith?