- Understanding Homo Economicus in Deeper Terms Garreth Bloor, Law & Liberty

- The Homo Economicus is “The Body” of the Agent Federico Sosa Valle, NOL

- Worker ownership: threat or promise? Chris Dillow, Stumbling & Mumbling

- Flower Fires Setsuko Adachi, Berfrois

economic development

Nightcap

- Zombie history: a bleak vision of the past and present Sophie Pinkham, the Nation

- Pakistan’s elections and the precarious future of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor Andrew Small, War on the Rocks

- Populism in less developed countries is somewhat different Pranab Bardham, 3 Quarks Daily

- The BRICS hit the wall Guy Sorman, City Journal

Nightcap

- Violent Conflict and Political Development Over the Long Run: China Versus Europe Dincecco & Wang, Annual Review of Political Science

- Why was the 20th century not a “Chinese Century”? Brad DeLong, Grasping Reality

- Law and border Jacob Levy, Niskanen

- The story of Indian magic John Butler, Asian Review of Books

Nightcap

- Anti-communism as bad faith Chris Dillow, Stumbling & Mumbling

- Thinking about privilege Arnold Kling, askblog

- The dancing plague of 1518 Ned Pennant-Rea, Public Domain Review

- Are things getting better or worse? Branko Milanovic (interview), New Yorker

Nightcap

- If Hillary Hates Populism, She Should Love the Electoral College Ryan McMaken, Power & Market

- Why Are Some Libertarians So Conservative About Immigration? Christopher Freiman, Bleeding Heart Libertarians

- The Idea and Destiny of Europe Nick Nielsen, The View from Oregon

- Jobs, technical progress & productivity Chris Dillow, Stumbling & Mumbling

Hegemony is hard to do: China, globalization, and “debt traps”

As a result of an increasingly insular United States, with US President Donald Trump’s imposition of tariffs, China has been trying to find common cause with a number of countries, including US allies such as Japan, India and South Korea, on the issue of globalization.

While unequivocally batting in favor of an open economic world order, Chinese President Xi Jinping has also used forums like Boao to speak about the relevance of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) (also known as the One Belt and One Road Initiative, or OBOR). At the Boao Forum (April 2018), the Chinese President sought to dispel apprehensions with regard to suspected Chinese aspirations for hegemony:

China has no geopolitical calculations, seeks no exclusionary blocs and imposes no business deals on others.

There is absolutely no doubt that the BRI is a very ambitious project, and while it is likely to face numerous obstacles, it is a bit naïve to be dismissive of the project.

Debt Trap and China’s denial

Yet China, in promoting the BRI, is in denial with regard to one of the major problems of the project: the increasing concerns of participant countries about their increasing external debts resulting from China’s financial assistance. This phenomena has been dubbed as a ‘debt trap’. Chinese denialism is evident from an article in the English-language Chinese daily Global Times titled ‘Smaller economies can use Belt and Road Initiative as leverage to attract investment’. The article is dismissive of the argument that BRI has resulted in a debt trap:

It is a misunderstanding to worry that China’s B&R initiative may elevate debt risks in nations involved in massive infrastructure projects. Countries are queuing up to cooperate with China on its B&R initiative, but many Western observers claim the initiative will create a problem of debt sustainability in countries and regions along the routes, especially those with small economies.

The article begins by citing the example of Djibouti in Africa, and how infrastructure projects are generating jobs and also helping in local state-capacity building. It then cites other examples, like that of Myanmar, to put forward the point that accusations against Beijing of promoting exploitative economic relationships with participant countries in the BRI is far from the truth.

The article in Global Times conveniently quotes Myanmar’s union minister and security adviser, Thaung Tun, where he dubbed the Kyaukpu project a win-win deal, but it conveniently overlooked the interview of Planning and Finance Minister, Soe Win, who was skeptical with regard to the project. Said Soe Win in an interview with Nikkei:

[…] lessons that we learned from our neighboring countries, that overinvestment is not good sometimes.

Soe Win also drew attention to the need for projects to be feasible, and for the need to keep an eye on external debt (Myanmar’s external debt is nearly $10 billion, and 40 percent of this is due to China).

The case of Sri Lanka, where the strategically important Hambantota Port has been provided on lease to China (for 99 years) in order to repay debts, is too well known.

The new government in Malaysia, headed by Mahathir Mohammed, has put a halt on three projects estimated at over $22 billion. This includes the $20 billion East Coast Railway Link (ECRL), which seeks to connect the South China Sea (off the east coast of peninsular Malaysia) with the strategically important shipping routes of the Straits of Malacca to the West. A Chinese company, China Communications Construction Co Ltd, had been contracted to build 530km stretch of the ECRL. On July 5, 2018 it stated that it had suspended work temporarily on the project, on the request of Malaysia Rail Link Sdn Bhd.

The other two projects are a petroleum pipeline spread 600km along the west coast of peninsular Malaysia, and a 662km gas pipeline in Sabah, the Malaysian province on the island of Borneo.

During a visit to Japan, Mahathir had categorically said that he would like to have good relations with, but not be indebted to, China, and would look at other alternatives. The Malaysian PM shall also be visiting China in August 2018 to discuss these projects.

Conclusion

While Beijing has full right to promote its strategic interests, and also highlight the scale and relevance of the BRI, it needs to be more honest with regard to the issue of the ‘debt trap’ (especially if it claims to understand the sensitivities of other countries, and does not want to appear to be patronizing). While smaller countries may be economically dependent upon China, the latter should dismiss the growing resentment against some of its projects at its own peril. Countries like Japan have already sensed the growing ire against the Chinese, and have begun to step in, even in countries like Cambodia (considered close to China). A number of analysts are quick to state that there is no alternative to Chinese investment, but the worries in smaller countries with regard to Chinese debts proves the point that this is not the case. China needs to be more honest, at least, in recognizing some of its shortcomings in its dealings with other countries.

Nightcap

- How did the West get religious freedom? Mark Koyama, Defining Ideas

- Are asylum rights misguided? Tyler Cowen, Marginal Revolution

- What Does China’s 5th Research Station Mean for Antarctic Governance? Nengye Liu, the Diplomat

- The forthcoming changes in capitalism? Branko Milanovic, globalinequality

Nightcap

- The secrets of Katyn Louis Proyect, CounterPunch

- Europe’s curse of wealth Branko Milanovic, globalinequality

- The new Europeans Christopher de Bellaigue, NY Review of Books

- Nuclear diplomacy between Brazil and Argentina Sara Kutchesfahani, War on the Rocks

Nightcap

- How Alan Shepard Became First American in Space Rick Brownell, Historiat

- Public Debt: a global perspective Livio di Matteo, Worthwhile Canadian Initiative

- Italian voters head for euro showdown Alberto Mingardi, Politico EU

- What good is religion? Manini Sheker, Aeon

Nightcap

- Neo- and other liberalisms David Glasner, Uneasy Money

- How neoliberalism seeks to limit the power of democracies Patrick Iber, New Republic

- The Unacknowledged Success of Neoliberalism Scott Sumner, Econlib

- From oligarchy to republic: Lessons from the American South James H. Read, Law & Liberty

On Household Size and Economic Convergence

A few days ago, one of my papers was accepted for publication at the Scottish Journal of Political Economy (working paper version here). Co-authored with Vadim Kufenko and Klaus Prettner, this paper makes a simple point which I think should be heeded by economists: household size matter. To be fair, economists are aware of this when they study inequality or poverty. After all, the point is pretty straightforward: larger households command economies of scale so that each dollar goes further than in smaller households. As such, adjustments are necessary to make households comparable.

Yet, economists seem to forget it when times come to consider paths of economic growth and convergence across countries. In the paper, we try to remedy this flaw. We do so because there was a wide heterogeneity of household size throughout history – even within more homogeneous clubs such as the countries composing the OECD. If we admit, as the economists who study poverty and inequality do, that income per person adjusted for household size is preferable to income per person, then we must recognize that our figures of income per capita will misstate the actual differences between countries. In addition, if households grew homogeneously smaller over a long period of time, figures of income per capita will overstate the actual improvements in living standards. As such, we argue there is value in modifying the figures to reflect changing household sizes.

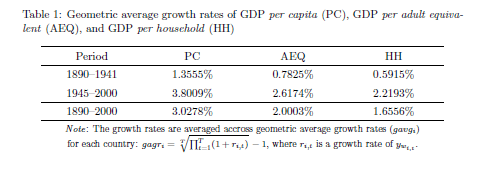

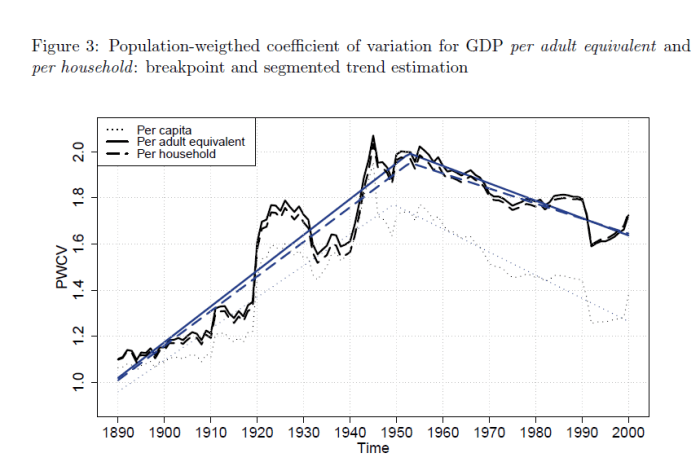

For OECD countries, we find that the adjusted income figures increased a third less than the unadjusted per capita figures (see table below). This suggests a more modest growth trend. In addition, we also find that up to the structural break in variations between countries (NDLR: divergence between OECD countries increased to around 1950) there was more divergence with the adjusted figures than with the unadjusted figures (see figure below). We also find that since the break point, there has been less convergence than previously estimated.

While the paper is presented as a note, the point is simple and suggests that those who study convergence between regions or countries should consider the role of demography more carefully in their work.

Divergence and Convergence within Italy

Two years, I wrote a post on this blog on the process of regional convergence in Italy. In that post, I made the observation that it seems that, economically, Italy was as fragmented at the time of the unification as it is today which made it an oddity in terms of regional convergence. To make that claim, I used this table of relatively sparsed out observations produced by Emanuele Felice: which was published in the Economic History Review:

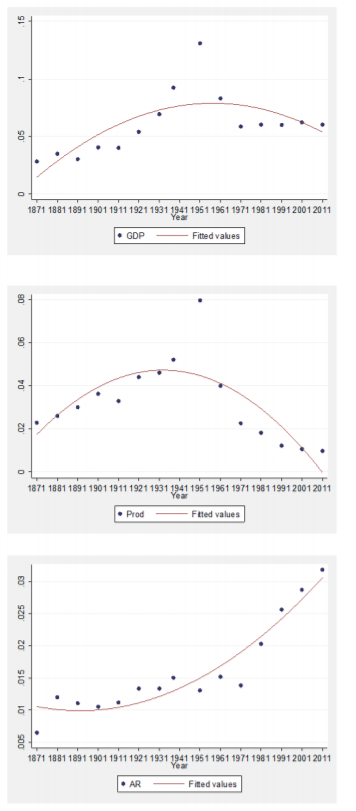

As one can see, there is a pronounced “lack” of integration for the Italy in terms of living standards. This is reinforced by a more “continuous” set of estimates produced, again, by Emanuele Felice (this time, its a working paper of the Bank of Italy) that now include the 1870s and go to 2011 (as opposed to 2001). This is the result, which I find fascinating. The first graph shows GDP per capita – for which there is divergence to 1951 and then a mild convergence thereafter but still well above the levels at the time of unification. More fascinating is the fact that productivity is at its most integrated since unification (2nd figure) suggesting a divergence in levels of labor activity (3rd figure). In these three graphs, you have a neat summary of Italian labor markets since 1870.

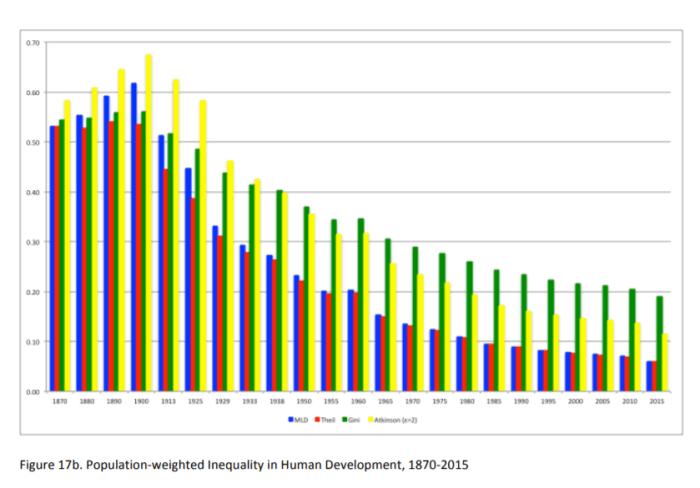

The great global trend for the equality of well-being since 1900

Some years ago, I read The Improving State of the World: Why We’re Living Longer, Healthier, More Comfortable Lives on a Cleaner Planet by Indur Goklany. It was my first exposition to the claim that, globally, there has been a long-trend in the equality of well-being. The observation made by Goklany which had a dramatic effect on me was that many countries who were, at the time of his writing, as rich (incomes per capita) as Britain in 1850 had life expectancy and infant mortality levels well superior to 1850 Britain. Ever since, I accumulated the statistics on that regard and I often tell my students that when comes the time to “dispell” myths regarding the improvement in living standards since circa 1800 (note: people are generally unable to properly grasp the actual improvement in living standards).

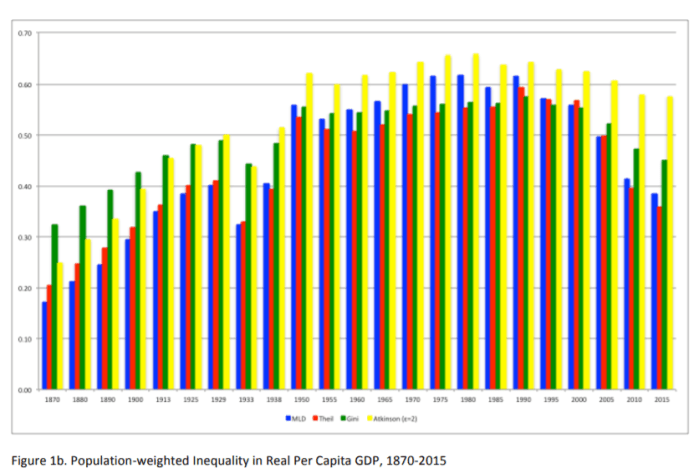

Some years after, I discovered the work of Leandro Prados de la Escosura who is a cliometrician who (I think I told him that when I met him) influenced me deeply in my work regarding the measurement of living standards and who wrote this paper which I will discuss here. His paper, and his work in general, shows that globally the inequality in incomes has faltered since the 1970s. That is largely the result of the economic rise of India and China (the world’s two largest antipoverty programs).

However, when extending his measurements to include life expectancy and schooling in order to capture “human development” (the idea that development is not only about incomes but the ability to exercise agency – i.e. the acquisition of positive liberty), the collapse in “human development” inequality (i.e. well-being) precedes by many decades the reduction in global income inequality. Indeed, the collapse started around 1900, not 1970!

In reading Leandro’s paper, I remembered the work of Goklany which had sowed the seeds of this idea in my idea. Nearly a decade after reading Goklany’s work well after I fully accepted this fact as valid, I remain stunned by its implications. You should too.

Nixon to Moscow, slavery’s toll on the economy

My latest is up over at RealClearHistory. An excerpt:

Nixon’s anti-Communist credentials were so sound that he could spend political capital making inroads with Communist enemies. His actions were viewed as safe by the American electorate because, for better or worse, the public saw Nixon as somebody who would not betray American values at the negotiating table with the Soviets. Nixon’s hawkishness provided moral cover for America’s withdrawal from Vietnam, and its peaceful overtures to the two most powerful and aggressively anti-capitalist regimes in the world (China and the USSR).

Please, read the whole thing.

Vincent has a great review up on Robert Wright’s new book about slavery, too. It’s at EH.net, a website dedicated to economic history, and here is an excerpt:

All of these amount to the same core point, those who reap the private benefits of slavery are content with their gains even though they come at a larger social cost and they will work to find ways to drive a wider wedge between the two by shifting costs onto other parties. Hence, slavery as pollution.

More here.

Explaining current Brazilian politics to known-Brazilians and why I believe this is time for optimism

It seems that many observers believe that Brazil’s current political situation is one of instability and uncertainty. Since the mid-1990s the national political scene has been dominated by two parties: the Worker’s Party (Partido dos Trabalhadores, PT, in Portuguese) and PSDB. Now, with the main leader of the PT imprisoned – former president Lula da Silva – the PSDB also seems to have lost its rationale. It is clear that this party never had faithful voters, only an anti-PT mass who saw in it the only viable alternative. Given these factors, it is true that a political cycle that began in the 1990s is coming to an end, but far from being a moment of uncertainty and pessimism, this may be the most fruitful moment in the country’s history, as it seems that finally classical liberalism is being vindicated in Brazil.

Brazil began its political history as a semi-parliamentary monarchy. As one observer of the time put it, the country had a “backward parliamentarism”: instead of parliament controlling the monarch, it was the emperor who controlled parliament. Moreover, the Brazilian economy was extremely based on slavery. In theory, Brazil was politically and economically a liberal country. In practice, it was politically and economically a country controlled by oligarchies.

With the proclamation of the republic in 1889, little changed. The country continued to be theoretically a liberal country, with a constitution strongly influenced by the North American one and a tendency to industrialization. In practice, however, Brazil continued to be politically and economically dominated by oligarchic interests.

The republic instituted in 1889 was overthrown in 1930 by Getúlio Vargas. Vargas was president from 1930 to 1945, and his political circle continued to dominate the country until 1964. Once again, political language was often liberal, but in practice the country was dominated by sectorial interests.

Vargas committed suicide in 1954, and his political successors failed to account for the instability the country went through after World War II. The Soviet Union had been trying to infiltrate Brazil since the 1920s, and this was intensified with the Cold War. The communist influence, coupled with the megalomaniacal administrative inability of Vargas and his successors, led the country to such an instability that the population in weight clamored for the military to seize power in 1964.

The military that governed Brazil between 1964 and 1985 were influenced mainly by positivism. In simple terms, they were convinced they could run the country like a barracks. For them, the motto “order and progress” written on the Brazilian flag was taken very literally. One great irony in this is that Auguste Comte’s positivism and Karl Marx’s communism are almost twin brothers, products of the same anti-liberal mentality of the mid-19th century. The result was that Brazilian economic policy for much of the military period was not so different from that of the Soviet Union at many points in its history: based on central planning, this policy produced spectacular immediate results (the period of the “Brazilian miracle” in the early 1970s), but also resulted in the economic catastrophe of the 1980s.

However, the worst consequence of the military governments was not in the economy but in the political culture. The military fought against communism in a superficial way, overpowering only the guerrillas and terrorist groups that engaged in armed struggle. But in the meantime, many communists turned to cultural warfare, joining schools, universities, newsrooms, and even churches. The result is that Brazilian intellectual life was taken over by communism.

Fernando Henrique Cardoso, elected president in 1994, is an important Brazilian intellectual. Although not an orthodox Marxist, his lineup is clearly left-wing. The difference between FHC (as he is called) and a good part of the Brazilian left (represented mainly by the PT) is that he, like Tony Blair in England and Bill Clinton in the US, opted for a third way between economic liberalism and more explicit socialism. In other words, FHC understood, along with leading PSDB leaders, that the Washington Consensus is called a consensus for good reason: there is a set of economic truths (pejoratively called neo-liberals) that are no longer the subject of debate. FHC followed these ideas, but he was heavily opposed by the PT for this.

Since the founding of the PT, in the late 1970s, Lula’s speech was quite radical, explicitly wishing to transform Brazil into a large Cuba. But Lula himself surrendered to the Washington Consensus in the early 2000s, and only then was he able to be elected president. Once in office, however, Lula commanded one of the greatest corruption scandals in world history. In addition, his historical links to the left were never erased. Although in his first term economic policy was largely liberal, this trend changed in his second term and in the presidency of his successor, Dilma Rousseff.

Today Brazil is still living in an economically difficult period, but an ironic result of more than a decade of left-wing government (especially the PT) is the strengthening of conservative and libertarian groups in Brazil. In the elections from 2002 to 2014 it was virtually impossible to identify candidates clearly along these lines. In this year’s election, we expected several candidates to explicitly identify themselves as right-wing. Jair Bolsonaro, the favorite in contention, is not historically a friend of the free market, but his more recent statements demonstrate that more and more he leans in this direction.

It is possible that in 2018 Brazil will not yet elect an explicitly libertarian president. But even so, the economic transformations initiated by FHC seem now to be vindicated. Only with the strengthening of the Internet did Brazilians have real access to conservative and libertarian ideas. With that, one of the most important political phenomena in Brazil in the last decade is the discovery of these ideas mainly by young people, and it is these young people who now cry for a candidate who defends their ideas. Bolsonaro seems to be the closest to this, although there are others willing to defend similar economic policy. After more than a decade of governments on the left, it seems that Brazil is finally going through a well-deserved right turn.