Daron Acemoglu & James Robinson acknowledge that the weakest point of their theory consists of recommendations to “break the mold.” How to change the historical matrix that leaves the nations stagnant in extractive political and economic institutions, or that move them back from having inclusive economic institutions with extractive political institutions to being trapped in exclusively extractive institutions with the risk of falling into a failed state. This brings us to Douglass C. North and his theory of institutional change.

Although he published works before and after Institutions, Institutional Change and Economic Performance, this book can be taken as the archetypal expression of neo-institutionalism. In the United States, institutionalism, whose main speaker was the Swedish immigrant Thorstein Veblen, was the local expression of what in Europe was known as “historicism”: a romantic current, inspired by Hegelian idealism, which denied the universal validity of institutional rules and claimed the particularism of the historical experience of each nation. American historicism was called institutionalism, because it concentrated the sciences of the spirit in the empirical study of the institutions given in the United States.

On the contrary, North’s school is called “neo-institutionalist” because it does exactly the opposite: it studies the phenomenon of institutions from a behavioral point of view and, therefore, universal. As already noted here, for North institutions are limiting the choice of the rational agent in his context of political, economic and social interaction. These limitations are abstract; that is, they are not physical, like the law of gravity, nor do they depend on a specific and specific order of authority. Examples of these abstract limitations can be found in social customs and uses, in moral rules, in legal norms insofar as they are enunciated in general and abstract terms.

Attentive to such diversity, Douglass C. North groups institutions in formal and informal. Within the formal institutions we find, unquestionably, the positive law, in which its rules of formation and transformation of the statements that articulate them can be identified very clearly. In a modern democracy, laws are sanctioned by the legislative body of the State. Meanwhile, the rules of formation and transformation of statements concerning morality are more diffuse – previously, Carlos Alchourrón and Eugenio Buligyn, in Normative Systems, had used this distinction to support the application of deontic logic to law, since deontic statements of law are much more easily identifiable than those of morality.

On the other hand, North distinguishes two types of institutional change: the disruptive and the incremental. An example of disruptive institutional change can be a revolution, but it can also be a legislative reform. The sanction of a new Civil Code, entirely new, can mean a disruptive change, while partial reforms, which incorporate judicial interpretative criteria or praetorian creations, can be examples of incremental changes.

Institutional changes do not necessarily have to come from their source of creation or validity. Scientific discoveries, advances in transport and telecommunications, information technologies, are some of the innovations that can make certain institutions obsolete or generate a new role or interpretation for it, depending on the open texture of the language.

Therefore, following the tradition of Bernard Mandeville and Adam Ferguson, neo-institutionalism admits that there are unintended consequences in the field of institutional change. Not only the incremental change of institutions, be they formal or informal, depends largely on changes in the cultural and physical environment in which institutions are deployed. Also the disruptive and deliberate change of a formal institution can generate unforeseen consequences, since it is articulated on a background of more abstract informal institutions.

Both Acemoglu & Robinson and North acknowledge that there is no universal law of history that determines institutional change -i.e., they deny historicism, as Karl R. Popper had defined it at the time-; what we have, on the other hand, is an “evolutionary drift,” a blind transformation of institutions. In this transformation, political will and environmental conditions interact. The latter not only limit the range of options for the exercise of “institutional engineering,” but also introduce an element of uncertainty in the outcome of such institutional policies, the aforementioned unintended consequences.

Much more complex is to identify which components are included in that black box that is called “environment” (environment). In principle, there could reappear the creatures that both William Easterly and Acemoglu & Robinson had banished from their explanations: the geography, culture and education of the ruling elites; more sophisticated elements such as the one referred to in the previous paragraph could also be incorporated: technological change. However, the discoveries of science would have no impact if the institutional framework pursued “creative destruction”, seeking to protect already installed activities from competition, or a lifestyle threatened by technological innovation.

We arrive here at a seemingly paradoxical situation: the institutions’ environment is the institutions. Using the Douglass North classifications system, one could try as a solution to this paradox the assertion that formal institutions operate on the background of informal institutions, which escape political will, and that disruptive institutional changes occur in a context of other institutions that are transformed in an incremental way. From this solution to reintroduce culture as a factor of ultimate explanation of institutional change, only one step remains.

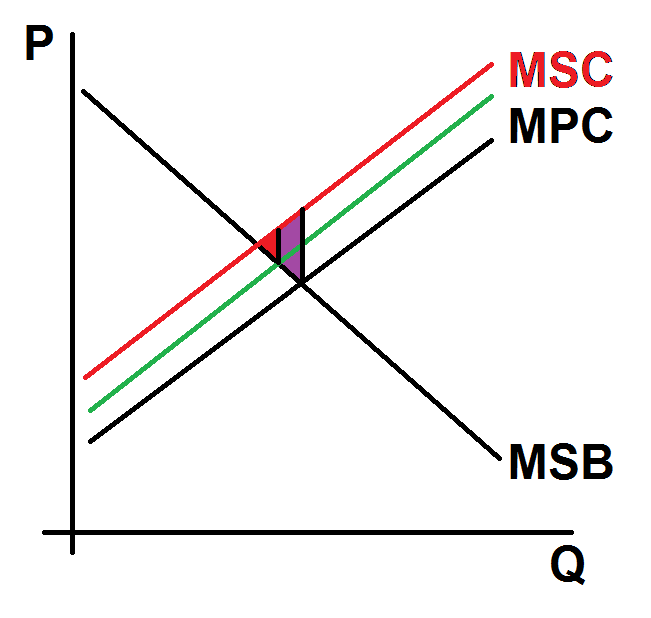

At the other extreme, following the typologies used by Acemoglu & Robinson, the institutions can be political or economic and these in turn can be extractive or inclusive, jointly or alternatively. Inclusive economic institutions within a framework of extractive political institutions can result in a limitation of creative destruction and, consequently, produce a regression to extractive economic institutions. In the institutional dynamics of Acemoglu & Robinson, history can both progress and regress: from economic institutions and extractive policies it can be involuted even to situations of failed state and civil war. To reach the end of history, with inclusive institutions, seems to depend on the conjugation of a series of favorable variables, among which is the political will; while to fall back into chaos and civil war it is enough to let go. Without looking for it, the conceptual background of Why Nations Fail rehabilitates the thesis of Carl Schmitt insofar as it presupposes that in the background of human interaction there is no cooperation but conflict.

For his part, William Easterly in The Elusive Quest for Growth does not ask these questions, but simply works under a hypothesis that already has it answered: whenever there is human interaction, there will be a framework of incentives and such a framework of incentives will have certain universal characteristics. Douglass C. North’s central concern in Institutions, Institutional Change, and Economic Performance, as well as that of Acemoglu & Robinson in Why Nations Fail, was to establish patterns of events and conditions that made some nations be prosperous while others could not emerge from stagnation. That is, they are works that must necessarily be about the differences between one country and another and, therefore, emphasize the different conditions. Notwithstanding that both North and Acemoglu & Robinson expressly shun culturalist explanations, but instead postulate abstract models and typologies of institutions and institutional change to be applied universally, when the moment of exemplification arrives, they must necessarily resort to the differences between countries and regions. While it is true that both books resort to the description of the problems of the southern United States when illustrating how certain institutions generate results similar to those of third world countries, the culturalist explanation is always available.

In contrast, William Easterly in his The Elusive Quest for Growth: Economists’ Adventures and Misadventures in the Tropics focuses almost exclusively on countries with low economic performance and only tangentially refers to cases of high performance. Therefore, in his work, the empirical analytical tools used to dissect it are well separated. To do this, Easterly will not only use a utility-maximizing rational agent model, but will also enunciate abstract models of universally valid human interaction.

In the first part of the work, Easterly describes the failed panaceas of growth: direct aid, investment, education, population control, loans to make adjustments and subsequent debt forgiveness. Affirms that such policies invariably failed because they did not take into account the basic principle of the economy that indicates that people respond to incentives (people respond to incentives, a statement that is repeated as a mantra throughout the book). While acknowledging that in some cases of extreme poverty and bad luck it is necessary for governments to take direct action to help people escape from poverty traps, the author proposes as the main means for people to take a path of prosperity: work to establish the right incentives. It clarifies, however, that this should not be a new panacea but a principle to be implemented little by little, displacing the layers of vested interests impregnated with the wrong incentives and allowing the entrance of the right incentives.

These incentives, right or wrong, do not depend on the culture, nor on the education of the elites, nor on geography. On the contrary, they consist of abstract models of human interaction, which can materialize at any time or latitude. Since the main interest of The Elusive Quest for Growth is, precisely, growth, such models concern this matter, but nothing prevents future research from identifying other abstract patterns of behavior that allow us to infer incentives to address other issues, such as crime, equity, violence, etc.

Some incentive structures that Easterly describes in relation to the problem of growth are the following: conditions for increasing returns – instead of decreasing ones – that come from technological innovation, which in turn depend on phenomena identified as “leakage of technological knowledge” (leaks of technological knowledge), “combination of skills” (matches of skills) and traps (traps) of poverty -although there are also wealth traps.

Technological knowledge has the capacity to filter into a population because it is mainly abstract. It can be exemplified in an accounting system, the practice of carrying inventories, literacy, techniques and procedures for the production, distribution and sale of products, etc. If the technological knowledge consisted exclusively of physical machinery, then yes it would be to a point where yields would become decreasing. On the contrary, understanding technological knowledge as consisting of “abstract machines”, it acquires the characteristics of a public good: it is not consumed with its use nor can it be exclusive. This is how technological knowledge can be extended in a society, multiplying the productivity of its members without entering into diminishing returns.

Also, following the ideas of the recent Nobel Prize in Economics Paul Romer, Easterly highlights that technological change can generate increasing returns thanks to the work of an endogenous agent of the economy, the entrepreneur. Being the labor force a fixed factor of production with respect to machinery, it is expected that, at a certain point, capital will generate diminishing returns, thus conditioning the growth rate of an economy (the main concern of The Elusive Quest for Growth). For its part, the entrepreneur is not only that agent of the economy who discovers new business, he also discovers new uses for existing capital goods. Easterly does not mention it, but this is also the main conclusion reached by Ludwig Lachmann in his work Capital and Its Structure. This work of the entrepreneurs, to find a new utility for a set of capital goods that had come to generate diminishing returns, making them continue to generate increasing returns is what frees the rate of growth of the economy from the limits of technological change and, in turn, makes it depend on the endogenous factor of the economy: the incentives for entrepreneurs to develop their activity -which some call creative destruction.

[Editor’s note: Here is Part 5 and here is the entire, Longform Essay.]