I often encounter the argument that immigrants, especially Muslims, are so different from the populations of their host countries that they threaten the institutional foundations of these societies. As a result, the logic goes, we must restrict immigration.

I do not accept that argument as valid nor do I accept it as sufficient (in the case I am wrong) to make the case in favor of further restrictions on immigration.

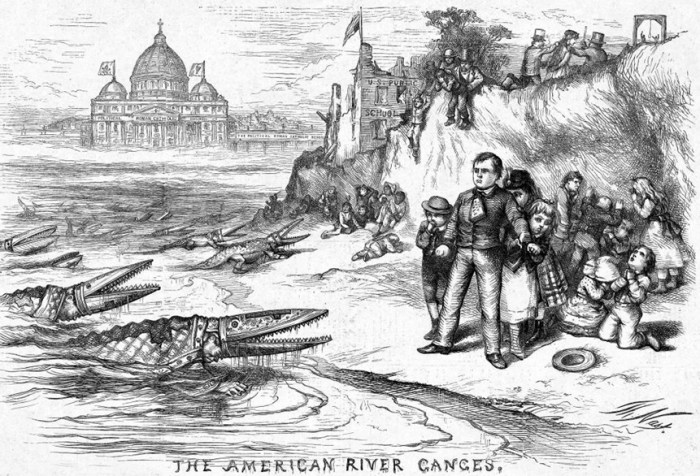

First of all, the “social distance” between immigrants and the hosts society is very subjective. The caricature below offers a glimpse into how “unsuited” were Catholic immigrants to the US in the eyes of 19th century American natives. Back then, Catholics were the papist hordes invading America and threatening the very foundations of US civilization. Somehow, that threat did not materialize (if it ever existed). This means that many misconceptions will tend to circulate which are very far from the truth. One good example of these misconceptions is illustrated by William Easterly and Sanford Ikeda on the odds of a terrorist being a muslim and the odds of a muslim being a terrorist. Similar tales (especially given the propensity of Italian immigrants to be radical anarchists) were told about Catholics back then. So let’s just minimize the value of this argument regarding going to hell in a hand basket.

But let us ignore the point made above – just for the sake of argument. Is this a sufficient argument against more immigration? Not really. If the claim is that they hinder “our” institutions, then let them come but don’t let them participate in our institutions. For example, the right to vote could be restricted to individuals who are born in the host country or who have been in the country for more than X-number of years. In fact, restrictions on citizenship are frequent. In Switzerland, there are such restrictions related to “blood” or “length of stay”. I am not a fan of this compromise measure (elsewhere I have advocated the Gary Becker self-selection mechanism through pricing immigration as a compromise position).*

The point is that if you make the argument that immigrants are different than their host societies, you have not made the case against immigration, you have made the case for restrictions against civic participation.

* Another “solution” on this front is to impose user fees on the use of public services. For example, in my native country of Canada, provincial governments could modify the public healthcare insurance card to indicate that the person is an immigrant and must pay a X $ user fee for visiting the hospital. Same thing would apply for vehicle licencing or other policies. Now, I am not a fan of such measures as I believe that restrictions on citizenship (but offering legal status as residents) and curtailements of the welfare state are sufficient to deal with 99% of the “problem”.