From an email I sent my principles of economics students:

Since we can’t have classes this week and the midterm is postponed a week, I felt chatty and wanted to share at least a few thoughts about why so many people are without power.

tl;dr: see the graph below. Prices are fixed. Supply shifts left, demand shifts right = instant shortages. This is not an easy problem to solve.

Issue #1 is that bad weather events increase demand – demand shifts to the right. Issue #2 is that energy prices are really sticky. We’ll be getting to this in March, but in energy markets we sign contracts with our energy providers that lock in the price of electricity for 1-2 years at a time. When demand increases, the price doesn’t! Further, some contracts allow us to smooth the bill out over 12 months, so if I need extra $12 of electricity today, I don’t actually pay for it today: I’ll pay for it by having a $1 higher electricity bill over a 12 month period. That does two things. a) It means that energy demand curves are really vertical, a small change in price doesn’t change my electricity consumption much; and b) when demand increases, prices don’t. That ruins the market price signal that tells you and me to conserve electricity. Issue #3 of course is that it is really amazingly expensive to increase electric capacity. That means that energy supply curves are also really vertical. Even if energy firms COULD raise prices, they can’t increase the quantity supplied in the short run. In the longer run, we have time to build more plants and add capacity, but in the short run we’re stuck with what we have.

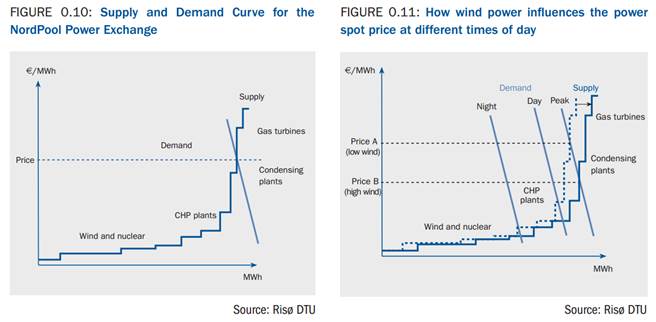

The graph above shows the marginal cost of different types of energy. Some are energy that is easy to turn on and off, but expensive (eg. oil). Some are energy that is really, really hard to turn on and off at will (eg. nuclear) but very cheap. And producing more energy than you need is bad. So you build enough cheap stuff that you know for 100% positive will always be needed, and then you build expensive stuff to handle changes in demand. That’s the short version, anyway. It means that producing a little extra electricity is really expensive and there is a hard limit to much extra we can produce – eventually supply curves are completely vertical!

My friends on the right tend to send blame towards green energy. And they have a point! Renewables are temperamental – with too many clouds solar doesn’t do anything, and frozen blades can’t turn wind energy turbines. The impact of the storm is to shift energy supply curves to the left, and the more the grid relies on renewables, the bigger that shift is. The basic problem renewables have had is that it’s really difficult to STORE their energy for future use. If we could create really large energy reservoirs, we could store Texas’ abundant solar and wind energy for a literally-rainy day.

So we have supply curves shifting left at the same time demand curves are shifting right and prices can’t move … the final result is massive shortages! Now what could be done about that?

My friends on the left tend to blame deregulation. Sadly, not one of them is spelling out exactly what regulation they think would solve this problem. Let me be generous to them and imagine they mean the following: if the government ran (rather than regulated) the energy grid, they would build a greater capacity than we typically use.

And they have a point. Energy is like the opposite of the hotel industry. In the hotel industry, you don’t build the hotel based on AVERAGE, normal operations. In Stephenville, you build a hotel large enough to accommodate people who come for graduation. The cost of having unused rooms is fairly low – you still need to keep the room cool in case someone needs it, and you want to hire someone to dust it, but it just sits there most of the time. Then you rake in big money when demand suddenly increases. The energy industry is the opposite: it is very expensive to build capacity and it is also expensive to maintain it. Whether you are a private firm or a government, the money to maintain unused generators has to come from somewhere.

How do we afford that? In the market, energy prices are actually set a little bit higher than equilibrium so that supply > demand. That ensures we have plenty of electricity to handle normal, typical demand fluctuations. We pay for that excess capacity during the normal part of the year so that when temperatures are particularly high or extra low, the grid can handle it.

The government has a different problem, though. If electricity is publicly-run, they will tend to set the price lower than the market would and make up the differences with taxes. That further divorces energy use from the price paid. We would have a higher quantity demanded at all times (wasteful). Add in that governments generally do a bad job running businesses (wasteful) and in order to have that excess capacity we would have to be willing to pay higher taxes (and lower energy bills) for many years to make up for the extra expense. Most governments, like most markets, will therefore tend to undersupply for an emergency because the voters don’t want to pay higher taxes and there is no such thing as a free lunch. So it’s not 100% clear that this would solve the problem. Europe has power outages that affect millions too.

Why? Healy and Malhotra: Governments respond to incentives, and voters give the wrong incentives: “Do voters effectively hold elected officials accountable for policy decisions? Using data on natural disasters, government spending, and election returns, we show that voters reward the incumbent presidential party for delivering disaster relief spending, but not for investing in disaster preparedness spending. These inconsistencies distort the incentives of public officials, leading the government to underinvest in disaster preparedness, thereby causing substantial public welfare losses. We estimate that $1 spent on preparedness is worth about $15 in terms of the future damage it mitigates. By estimating both the determinants of policy decisions and the consequences of those policies, we provide more complete evidence about citizen competence and government accountability.”

Bottom line: there isn’t an easy solution to weather events that happen once in a hundred years, whether it’s floods or hurricanes or … whatever this white, powdery substance is that’s blanketing my lawn. The basic problem is scarcity in a market where price signals don’t work (by design) at a time when supply shifts left and demand shifts right. To the extent climate change means more frequent extreme events, this will be a growing problem.

Weatherization is the biggest problem. Not all wind power went offline, and some wind power performed behind expectations. Wind power generation is done reliably in more extreme environments, likely with higher upfront cost. Solar generally performed as expected, as far as I can tell.

A poorly winterized wind mill, a poorly winterized nuclear plant and a poorly winterized (or fuel starved) natural gas plant generally do the same thing in conditions like this: not make power.

Regulation would include incentive to pay for winterizing for 50-100 year events.

Texas’s avoidance of regulation is also responsible for stalling and reduction in scope of the Tres Amigas SuperStation.

I get you were trying to focus on a specific relevant aspect of the problem. but you get an F for spreading misinformation without actually looking into the issues.

Thank you for adding two other elements to the discussion. Your primary point is to show that not only wind power supply shifted left. That doesn’t qualitatively change anything I said.

I actually think subsidizing winterization would be an excellent argument for discussing public goods and how Pigouvian taxes and subsidies help get market prices right. That’s a whole other set of arguments pro and con. Personally, I’d much prefer your solution to the strawman I set up. Sadly, I’m running a macro class – only one month in – and we won’t be hitting public goods, which is in our micro class.

I find your F grade comment high-handed and uncivil.

To keep pulling on one thread you mentioned around raising prices to cause demand to be lower… you pointed out all the reasons this doesn’t happen due to how contracts are structured. However, ignoring practical considerations, imagine a system that could, in real time, inform consumers what the price of their electricity was. In times like these, raise prices, and all of a sudden, more people will make damn sure their basement light isn’t left on… making it possible for more households to have power.

To allay social welfare concerns, you could have a graduated system, and only change prices for higher tiers of usage.

How to implement such a system? No idea. But I’m a big fan of using pricing as a signal to demand during natural or other disasters. Charge $5 per water bottle in a disaster area? Yup, on the surface you’d be morally bankrupt, but you sure would make people think twice about buying that third palette of water, thereby enabling more families to have *some* water. Donate the excess profits to relief organizations to clear your moral conscience.

The graph I copied also does a nice job explaining day and night pricing. To the extent we can get people to move their dishwasher and washing machine activities (eg) to the night time, we can rely more on cheaper base operations and that would be nice.

A system that informed consumers in real time … I get an email from my power company when our consumption is higher than average (usually means we did two loads of laundry that day). If they sent me a text instead to let me know that power usage was approaching, but had not yet hit the higher use levels, that could do something interesting. It’d be easy enough to automate given that they already monitor my daily usage. Tougher in an apartment building I’d imagine…

}}} How to implement such a system? No idea. But I’m a big fan of using pricing as a signal to demand during natural or other disasters.

Nice, but the nature of current governmental interference in such things discourages this. Laws against “price gouging” will either come into play or be added to prevent any useful price signals from getting through.

A more proper legislative effort would be to apply excess profits from such things to ameliorating the issue for future instances (i.e., I assume you could divert some of those profits to increasing the base capacity, or additional weatherizing, perhaps).. But that’s not how legislatures work these days. They punish anyone who adds useful info to the price structure, and put the money into their own slushpile for spending on, oh, ice skating rinks in summer, free concerts with obscure musicians that no one wants to pay for… that kind of thing.

I consider this to be the inevitable result of making meaningful policy decisions based on errant belief in the hoax/grift that is the climate change industrial complex.

Without the climate change myth, coal would be viewed more realistically: It is not without its drawbacks. But it’s not destroying the planet either.

So we’ve given coal the heave-ho and substituted it with the unreliability of renewables.

And the price we pay is in lack of preparation for these not unprecedented but very uncommon events. Note that it’s been a hundred years since a storm this bad. How bad was climate change a hundred years ago? I’ll bet that the people who perished in this similar storm a hundred years ago would only have dreamed of having the choice and the technological capability to weather a storm like this with all the convenience and protection that reliable utilities represents.

Ironically, we now have that choice and that capability. But we’ve been convinced not to exercise that choice in the name of ” not warming the planet “.

Lunacy.

ProfTweed pointed out about that winterization is still an issue, even for coal plants. The question I worry about is incentivizing enough excess capacity to deal with once-in-a-century storms.

So I used to live in upstate NY. Storms this bad are called “Tuesday.” In Missouri, this level of snow is more like a once-a-year or a once-a-few. It makes good sense for any responsible company to plan that far ahead. 100 years? That’s harder to plan for no matter your mix of renewables. The fact that Texas got hit by a once-a-century set of hurricanes a few years ago, once-in-a-century flooding recently, and now once-in-a-century snowfall does lend at least some credence to the idea that the climate is more volatile than before.

Perhaps some of the problem is having electric grids organized by state rather than a more inter-connected grid. Excess demand in TX could be met by excess capacity in Florida. CA could pay companies in Nevada. Sadly, that would come with (additional) federal regulation, and I’m not optimistic that would help.

Correction: Texas is not connected to the rest of the states, while CA has at least some connection to its neighbors. It has other problems. I realized I misspoke.

If I understand correctly, though, nukes and gas and so forth were not anywhere near as severely affected by this weatherization failure:

—–

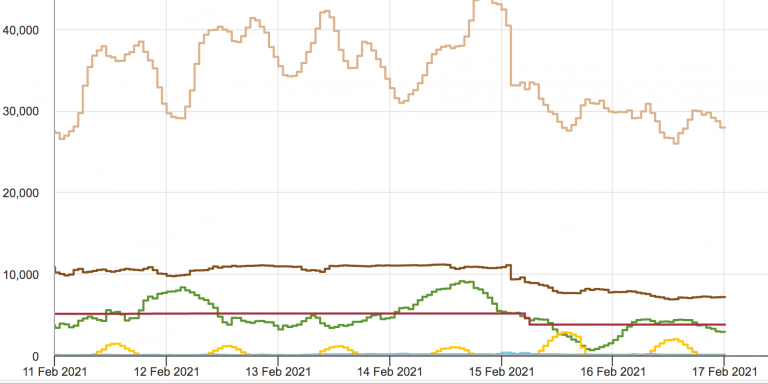

Here is the overall generation mix from February 11–17. The upper light brown line is gas-fired generation. The brown line starting at about 10,000 is coal. Green is wind, the yellow is solar, as is apparent from the daily pattern, and the almost-straight line starting at about 5,000 is nuclear.

Source is EIA…they have a lot of useful data, but you have to poke around a bit to find it.

https://www.eia.gov/beta/electricity/gridmonitor/dashboard/electric_overview/regional/REG-MIDA

—–

From the above — Coal and nukes went down by only about 10-20% ca. 15 Feb. Gas dropped by as much as 25%, but it was cyclic, and did not drop below its usual capacities, at the least.

Wind, OTOH plummeted by as much as 95%, it appears. And solar was only available during the day… “duh”… and actually did a little better than usual on the DAY of the 15th.

On the whole, it appears that wind was the only one with a real issue, though a failure to have excess capacity (which has been noted here and elsewhere) is at least one major problem. The nature of the Texas energy grid setup discourages the retention or development of excess capacity.

How might we impose good economics upon inherently politicized decisions?

(thinks: Boy, if I had an answer like that, I’d get a Nobel. Okay, let’s try to have a more productive comment than that…)

The Healy and Malhotra quote suggests that voters could impose good economics by punishing politicians who use bad economics, instead of punishing those who don’t give us enough handouts after a disaster. How to get voters to be more intelligent, that’s a problem that goes back to Aristotle at least.

Doing so in an era of extreme and increasing polarization makes it even harder – each side thinks they are the sole possessors of economic Light and Truth, so votes for My Team are assumed to be votes for Good Economics. The problems of heuristic voters are numerous and apparently growing.

I find it interesting you keep calling this a “once in a century” storm when Texas had similar freezes in 2011 and 1989. The 2011 one even caused power grid failures, and spurred a FERC report on the issue.

The latter is full of all the specific regulations that “the left” would like to see implemented. By the by.

I greatly appreciate the mention of the report. For those interested, the link is here: https://www.ferc.gov/sites/default/files/2020-04/08-16-11-report.pdf

My “once in a century” line in the comment above was based on locals’ remembrance. You are quite correct that this is more like once-in-15-years. I am told that when 2011 hit, they called it once-in-a-century.

For those who would like my very brief summary of their conclusions: they identify supply losses across many generator types as the primary cause. The two main reasons for supply losses were lack of winterization and poor planning for when generators would shut down for regular maintenance. They urge generators and planners to prepare for winter cold with the same urgency they already plan for summer heat, which might include regulation to require generators to submit a winterization plan and establish minimum winterization standards.

Interesting story about supply and demand, but I did find the graphs somewhat hard to follow. I do have one minor quibble about the “green energy” kerfuffle; electrical power generation switched from coal to natural gas because it is cleaner, and thus one can argue “green”.

A second unrelated technical point about electric power generation is all of these power plants (except for photovoltaic solar) spin a turbine, and all require water (even solar requires water to clean the panels). Areas of the world that don’t have temeperatures below freezing for extended periods of time typically don’t think about what happens when their water supply freezes. Some visionary thinker will create a process to convert energy into electricity that doesn’t require water, and become obscenely wealthy.

Lastly, I can’t imagine how bad the situation would be in Texas if all of the transportation machines were battery electric vehicles; the state would need to generate two to three times as much electricty to charge all them.

Is it such a good idea to have each recipient building’s entire electrical delivery relying on external power lines that are too susceptible to various crippling power-outage-causing events (for example, storms and tectonic shifts)?

I could really appreciate the liberating effect of having my own independently accessed solar-cell power supply (clear skies permitting, of course), especially considering my/our dangerous reliance on electricity. And it will not require huge land-flooding and potentially collapsing water dams.

However, apparently large electric companies can restrict independent use of solar panels.

Interviewed by the online National Observer (February 12, 2019), renowned linguist and cognitive scientist (etcetera) Noam Chomsky emphasized humankind’s immense immediate need to revert to renewable energies, notably that offered by our sun.

In Tucson, Arizona, for example, “the sun is shining … most of the year, [but] take a look and see how many solar panels you see. Our house in the suburbs is the only one that has them [in the vicinity]. People are complaining that they have a thousand-dollar electric bill per month over the summer for air conditioning but won’t put up a solar panel; and in fact the Tucson electric company makes it hard to do. For example, our solar panel has some of the panels missing because you’re not allowed to produce too much electricity …

People have to come to understand that they’ve just got to [reform their habitual non-renewable energy consumption], and fast; and it doesn’t harm them, it improves their lives. For example, it even saves money,” he said.

“But just the psychological barrier that says I … have to keep to the common beliefs [favouring fossil fuels] and that [doing otherwise] is somehow a radical thing that we have to be scared of, is a block that has to be overcome by constant educational organizational activity.”

I still think he’s putting it a bit mildly.

}}} my own independently accessed solar-cell power supply

So, you’re prepared to clean them regularly? Because even a 10% film can cause as much as a 50% reduction in power output.

Also, you’re prepared to pay not less than 3x your current price point for energy?

And to cover — offhand, about 30 sq. meters — of area with “little blue panels”? (Note: If you’re putting it on your roof, realize, you have to keep it clean, which means getting up there to clean them regularly… including keeping snow and leaves off of them, mind you… and guess what is the second most common cause of accidental death in the USA… Hint: it involves the application of gravity to the human body)

Then there’s the pollution problem — moving the extreme pollutant problem to China does not make it go away, and there’s still going to be the recycling issue later on in 10-20y when alllllllllll those panels being created go bad and need to be replaced/disposed of.

Yeah. I could very well be wrong, but you’re looking at some things, and not seeing ohhhh-so-many other things that are relevant to the “miracle of solar power”.

Kapisce?

}}} Interviewed by the online National Observer (February 12, 2019), renowned linguist and cognitive scientist (etcetera) Noam Chomsky emphasized humankind’s immense immediate need to revert to renewable energies, notably that offered by our sun.

OK, does it not occur to you that listening to a linguist tell you about power supply choices is not the wisest of expert choices?

Chomsky is an undisputed genius, but so was Einstein.

Einstein is known for this pronouncement:

You cannot simultaneously prevent and prepare for war.

Unfortunately, his expertise in physics did not extend into the realm of geopolitical reality. The absolute WORST situation you can be in with regards to prevention of war is to NOT be prepared for it. If you want to prevent someone so inclined from initiating a war with you, the better prepared you are to be in a war the better they will be dissuaded from its pursuit.

Ronald Reagan made a far more cogent and valid point, despite not being the kind of uber-genius Einstein undoubtedly was, when he said:

Of the four wars in my lifetime, none came about because the U.S. was too strong.

Q.E.D.: The worst way to prevent a war is to be unprepared for one. Einstein was flat out wrong, largely because he was speaking unfortunately well outside his sphere of expertise.

Chomsky is likewise. Energy and power development and distribution is well outside of his area of expertise, and everyone should grasp this and stop listening to anything he has to say about it, at least to the point of giving it more weight than some guy whose job it is to work on power lines for a living.

Chomsky is quoted and listened to far far too often outside the arenas where he knows jack and his smelly companion of.

I wouldn’t give much credence to Ronald Reagan, neither for cogence nor validity (especially when compared to Chomsky).

A good example of Reagan’s on-and-off tunnel-vision was his seemingly blind support of what has become a virtual corporate rule in the U.S. (although Canada is no better in regards to catering to big business lobbyists).

Too many of his White House events, speeches, news-media briefings and sound-bytes were like political sermons straight from his own copy of the Capitalist Manifesto.

Reagan may have been correct in his observation that, “Of the four wars in my lifetime, none came about because the U.S. was too strong”; however, I have long wondered what may have historically come to fruition had the U.S. remained the sole possessor of atomic weaponry.

There’s a presumptive, and perhaps even arrogant, concept of American governance as somehow, unless physically provoked, being morally/ethically above using nuclear weapons internationally.

After President Harry S. Truman relieved General Douglas MacArthur as commander of the forces warring with North Korea — for the latter’s public remarks about how he would/could use dozens of atomic bombs to promptly end the war — Americans’ approval-rating of the president dropped to 23 percent. It is still a record-breaking low, even lower than the worst approval-rating points of the presidencies of Richard Nixon and Lyndon Johnson.

My muse is: had it not been for the formidable international pressure on Truman (and perhaps his personal morality) to relieve MacArthur as commander, would/could Truman eventually have succumbed to domestic political pressure to allow MacArthur’s command to continue?

I guess we’ll never know for sure.

Right. I remember the cries to “nuke” Afghanistan after 9/11…

}}} In Tucson, Arizona, for example, “the sun is shining … most of the year, [but] take a look and see how many solar panels you see.

Tucson is an exception, not the norm.

The answer is in a concept referred to as “insolation”, with a relevant map for guidance:

This is best described as the average number of hours of sun available on a random day.

Even in an area like Arizona it’s only around 5.5-6 hours.

Given that the sun hits the earth at very close to 1kW/sq. meter, this means every square meter can produce — with 100% conversion (reality: 25%) is, in Arizona, about 5-6 kWh per DAY (real world: 1.5 kWh)

There is a REASON why solar needs to be endlessly subsidized.

In my own observation, the only solar that’s actually really worth seriously exploring is Ocean Thermal, and even that is somewhat iffy.